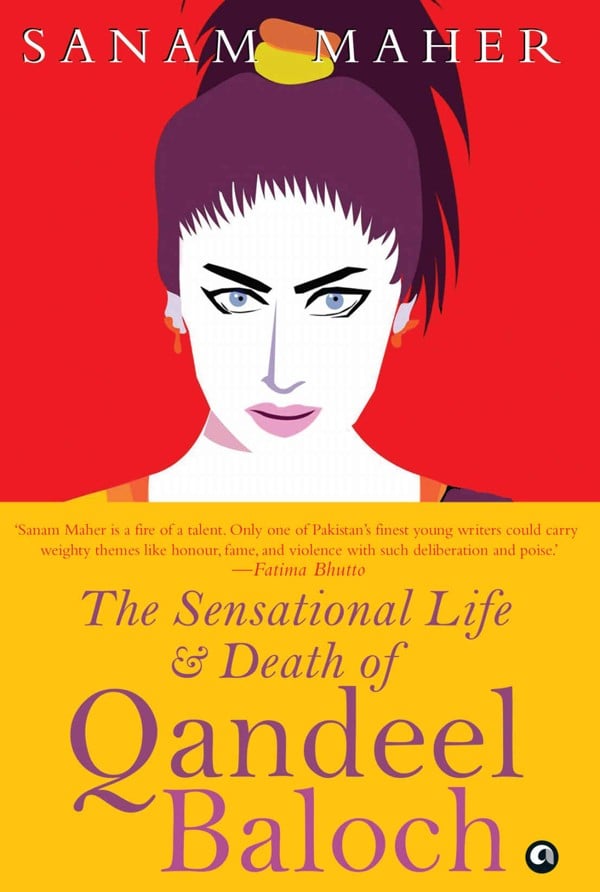

The Sensational Life and Death of Qandeel Baloch

by Sanam Maher

Aleph Book Company

I remember when internet provocateur Qandeel Baloch first made headlines on the Indian side of the border. Baloch was already infamous in Pakistan because of the suggestive videos she posted online, although they were quite innocuous by Western standards. But in March 2016, she announced on her Facebook page that she would perform a striptease for her followers and dedicate it to Shahid Afridi, then the Pakistani cricket captain, if his team won a hugely anticipated match against India.

And then she was dead, strangled by her brother in an “honour killing”, for allegedly bringing shame on her family.

Baloch played a caricature of a rich, self-involved bombshell in her videos (“How I’m looking?” she coos in one) and was unapologetically feisty in television interviews. Widespread fame – the kind that arrives seemingly out of nowhere in the YouTube era – and roles on the silver screen appeared to be just around the corner.

Instead, she became the highest-profile woman to lose her life for refusing to conform to the subcontinent’s regressive patriarchal norms. And the reputation of the woman written off by many as a desperate attention seeker changed instantly. Baloch was no longer just “Pakistan’s Kim Kardashian” – she had become a feminist icon.

To her credit, Maher set her ambitions higher than just writing a biography and what emerges is richer and more unsettling: an exploration of how an entire society can condemn a woman to death.

Baloch was born Fouzia Azeem to a poor family in the village of Shah Sadar Din, in Punjab province, where honour killings are common, individualism is routinely stamped out and the actions of women such as Baloch are seen as failures of both the family and the community.

Honour killings are also ubiquitous in Punjabi folklore. In Mirza Sahiban, a tragic story similar to Romeo and Juliet, a young woman and her paramour are brutally murdered by her brothers. She had staked a claim to her own sexuality, a transgression that had to be punished.

One of the most distressing takeaways from Maher’s book is the inevitability of Baloch’s death. If her brother had not murdered her, it might have been one of the many viewers who were transfixed by her videos but also posted death threats in the comments. Or it could have been friends of her brothers, who felt she was sullying the reputation of their village. Or it may have been the husband she fled.

When the book opens on the morning after her murder, the media – another group complicit in Baloch’s death – have breached ethical standards by broadcasting an image of her bloated corpse. And just before she was killed, newspapers had also printed images of Baloch’s passport, revealing her real name.

Blame is also assigned to Pakistan’s ineffectual institutions. The Federal Investigation Agency is tasked with handling cybercrime and should have investigated the misogynistic vitriol Baloch faced online, but instead it seems to focus on social-media users who post anti-military content.

Sexual abuse is rife in the women’s shelter where Baloch ends up after fleeing her husband, and one observer notes that only two kinds of women end up there: “Those who want to marry someone of their choice, and those who want a divorce.” Many women who return to their families face gruesome repercussions.

However, Maher’s book is not just a bleak roll-call of the horrors Pakistani women face in the intersections of culture and state, but also a tribute to female resilience against the odds. Khushi Khan, a model and fashion-show organiser who idolises Baloch, is forced out of the industry because of her family’s resistance to her job. Dad, who herself left an unhappy marriage, launches the Digital Rights Foundation to provide counselling for women who face targeted harassment online. And Jaffreyexplains how she braved societal pressure to become one of Pakistan’s first female police officers.

While Maher does not offer any new revelations about Baloch’s personality, the late social-media star is an indomitable presence. She unabashedly traded on her sex appeal online; her make-up and clothing were not simply a substitute for personality, they reflected her wish to transcend her lower-class status. One of her friends notes that he almost did not recognise the dead Baloch because she looked “like the maids who clean his house”.

Baloch may have tantalised millions with fleeting glimpses of her body, or gave them opportunities to laugh at her clearly put-on accent, but she was very much in on the joke. Her candour was no more apparent than when she talked of the son she left behind and discussed the violence she faced at the hands of her husband in one of her last interviews before her death.

Maher makes it clear that there is no contradiction between the sexy, confident Baloch we see in her videos and the damaged, vulnerable woman she was in real life. Two years after her death, Baloch’s cool-headed rationality – even though she was drawn into a vortex of debates about womanhood, virtue, Islam and sexuality – remains culturally subversive.

Pakistani comic book heroine fights corruption and honour killings

Maher makes some frustrating choices. The recurring device of using Baloch’s voice to respond to the narrative seems ill-judged, as it makes her appear unidimensional. And many readers will wish Maher had dug a little deeper into the dichotomous notions of womanhood that Baloch and her peers are forced to navigate.

For example, Khan notes that she herself was not able to secure jobs in liberal Islamabad because she wore the hijab. In another instance, Jaffrey invokes Benazir Bhutto, the late prime minister who she considers a role model because she always covered her head, in stark contrast to Baloch.

The Sensational Life and Death of Qandeel Baloch ends with an intriguing question: who really killed Qandeel Baloch? Yet, as the tapestry of narratives makes clear, the answer does not matter. Everyone from anonymous internet commenters to members of parochial communities, unyielding state institutions and religious organisations may have stood in her way, but Baloch’s bravery in what she called the mardon ki society (“society of men”) made her a symbol of feminist defiance. And a target.