France is dotted by former camps where Harkis – Algerians who fought for the French during Algeria's war of independence – were housed with their families after France lost its colony. Held in bleak conditions, scores died and were buried in makeshift graves. For years, relatives have fought to locate the bodies – and this week, they came a step closer to identifying the remains of some 50 people, most of them young children, who died at one of the most infamous camps in southern France.

Pressure from Harkis' descendants, backed by historians and journalists, has driven France to order excavations at two of the main internment camps since 2023.

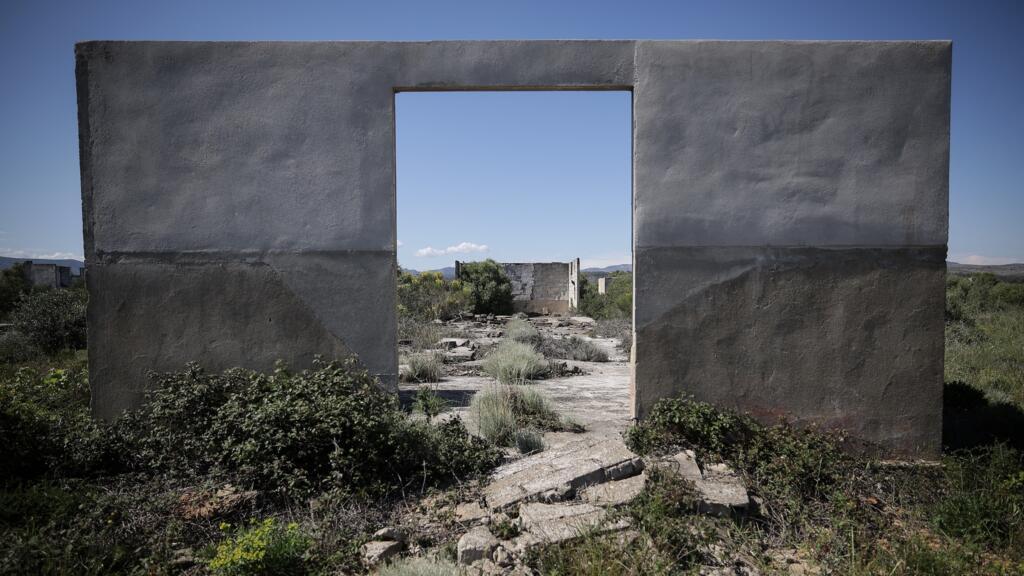

Digging at Rivesaltes, a repurposed World War II concentration camp that around 21,000 Harkis and their families passed through between 1962 and 1965, revealed a makeshift graveyard – but no bodies.

Since the discovery in November 2024, local authorities have been scrambling to trace the remains once buried at the site between the Mediterranean and the Pyrenees. They belong mainly to infants and children who didn't survive the cold, malnutrition and lack of medical care.

Official archives recorded that, when the French state sold the site to the local council in the mid-1980s, the Defence Ministry authorised the town to move the remains into its municipal cemetery. It did so unannounced, without notifying the relatives or marking the new resting place.

A search of the ossuary in February turned up four crates containing thousands of unidentified human bones, which were sent for analysis at a specialised laboratory in Marseille.

Earlier this week, forensic anthropologist Pascal Adalian met members of the families to give them the results: the bones belong to at least 49 different children aged less than three years old, as well as two adult women and one man, who died in the early 1960s.

These findings are consistent with what is known about the Rivesaltes dead, according to Bruno Berthet, secretary-general of the regional prefecture: "None of this invalidates the hypothesis that these are indeed the remains of Harkis who died in the camp."

Missing bones

For the families, there is still room for doubt.

"Professor Adalian cannot say with 100 percent certainty," said Marie Gougache, the spokesperson for people who lost relatives at the camp. "All the evidence suggests that these could be the bones of our late loved ones. But only DNA tests could confirm it 100 percent."

The analysis also found that the three adult skeletons were incomplete, Gougache told RFI. That raises the possibility that some remains were overlooked when the Rivesaltes site was cleared – especially since experts from the National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research found two hand or foot bones when they excavated the camp last year.

"Now, with Professor Adalian's findings, we have confirmation that some bones are missing, and I wonder: are there still some left within the grounds of the old cemetery?" Gougache asks.

With so many remains jumbled together, including the fragile bones of babies, the chances of identifying each individual appear slim.

After their removal came to light, five families filed a complaint with the public prosecutor for violation of a grave, damage to a corpse and concealment of remains. The way the bodies have been treated is, for some relatives, another indignity among many suffered by Harkis and their descendants.

French Senate formalises apology to Algerian Harkis and their families

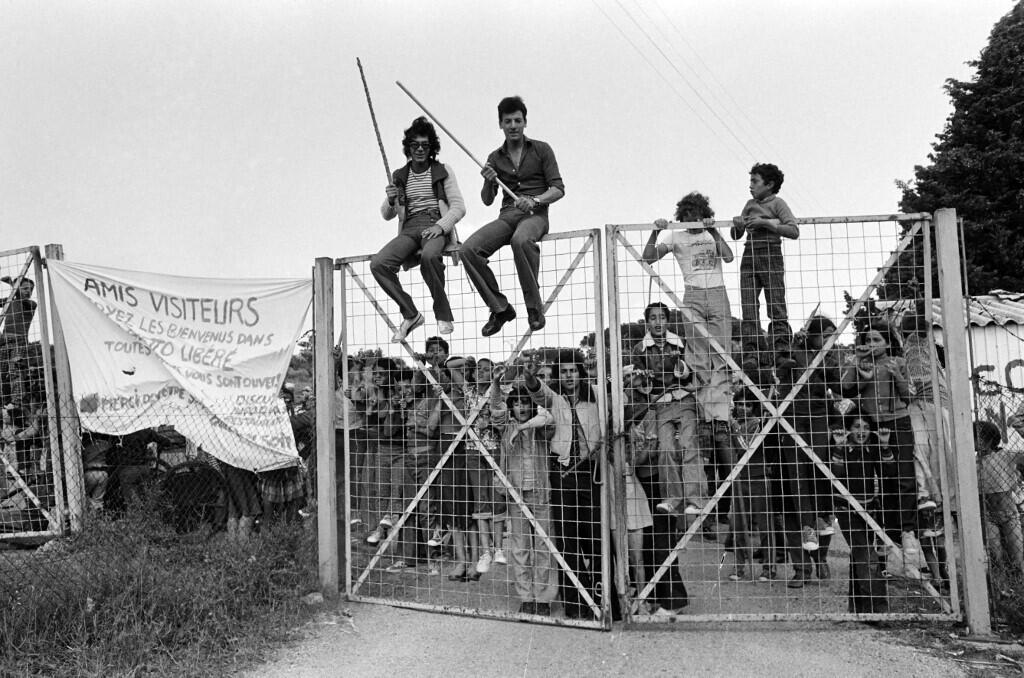

Roughly 90,000 fled to France after Algeria's independence in 1962, where many ended up in one of around 80 military-run camps designated to hold them. Some spent years in substandard accommodation, in some cases sleeping in tents or on bales of straw, and fenced off from the rest of the population.

It is not known how many died in the camps. Some estimates put the number of child fatalities in the first three years after the war at 300 to 400, alongside a much smaller number of adults.

France to compensate more Harki families for mistreatment after Algerian War

'Ghost graves'

Of 146 people known to have died while interned at the Rivesaltes camp, 101 were children. While French authorities kept records of the deaths, according to families, they did not always inform parents where their children were buried.

"When our parents arrived, they couldn't read or write," says Abdallah Krouk, the son of Harkis and now a campaigner for recognition of their rights. "When you get there, there are camp leaders who take your baby away and say, 'Madam, don't worry, we'll take care of it...' And 60 years later, you find out that they were in wasteland.

"That's what we call ghost graves."

Such practices were common to other internment camps, Krouk says.

At Saint-Maurice-l'Ardoise, a camp in southeastern France that held at least 6,000 Harkis, the military recorded 71 deaths between 1962 and 1964, 61 of them children aged two or less.

Excavations there in 2023 uncovered 27 child graves in an abandoned field. Archaeologists found evidence that the tombs were originally marked, but had fallen into such disrepair that they were no longer identifiable.

That site is now a national burial ground maintained in perpetuity by the French state.

At Rivesaltes, a museum commemorates the various groups interned throughout the camp's history and a plaque lists the Harki children known to have died there.

Families face the choice of placing their relatives' remains in a new, marked memorial within the town cemetery or moving them back to the camp.

Krouk told RFI they deserved, finally, a dignified burial: "They are children of the Republic, they are French citizens."