It was May 2025, and Chris Bird was sitting in his living room in Chippenham, Wiltshire, surrounded by amps, guitars, and books. On the floor, in the centre of the room, a Fender Precision bass lay in an unopened flight case. Chris hadn’t played guitar for a while, and that meant that the calluses on his fingers – earned from decades of playing – had faded.

“So steel strings are out,” he said. He nodded at the flight case. “But maybe I can play bass.”

He scrolled through Spotify and played the music of Gareth Dylan Smith, a jazz drummer Chris had played with in his first-ever band, when they were both still at school. “I should have been on that album,” said Chris. But the album was recorded in 2024, he explained, “and I just couldn’t.”

Maybe you could record something from home, a visitor suggested, and send it to him, get on the next one? “Maybe,” he said. “Maybe I could play some bass.”

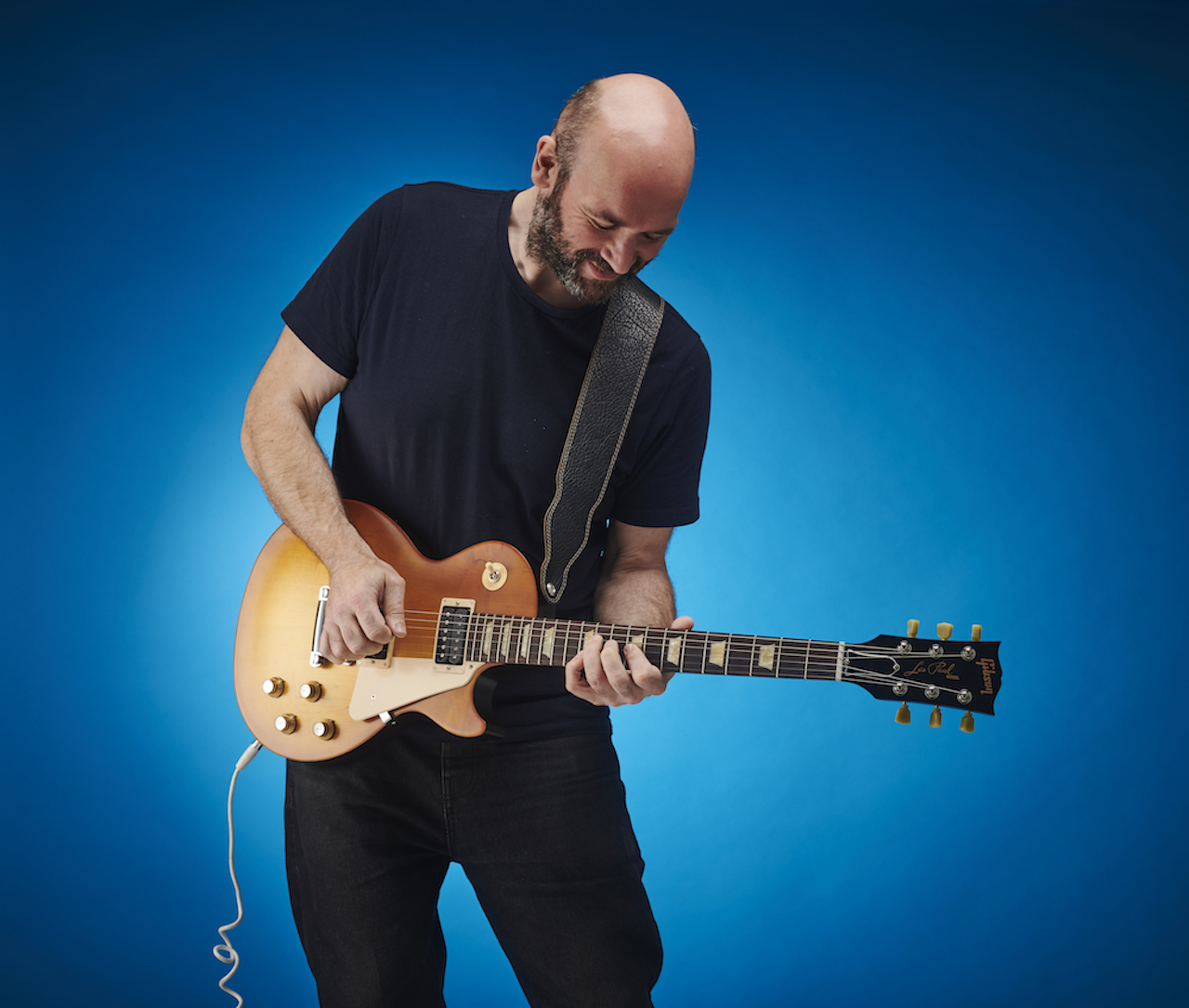

Chris Bird worked on Total Guitar magazine for 17 years, from 2007 to 2024. Launched in 1994, Total Guitar – known to the team that worked on it as TG – quickly became the biggest-selling guitar magazine in the UK and Europe, targeted at young players just finding their way on guitar. But by the mid-2010s, the presence of free tab sites and video lessons on YouTube meant that the attention of young players was elsewhere.

Total Guitar had eight Editors in its 30-year lifespan before it ceased publication in October 2024. Chris Bird was the last Editor of TG.

It wasn’t something he dwelt on. In April 2024, Chris was diagnosed with Stage 4 bowel cancer. It had spread to his liver. “At this stage,” he said, “I just need to outlive my mum.”

When he was six, Chris told his mum, Sue, that he wanted ‘a rhythm stick’ for Christmas. Chris can’t remember saying this, but it tickled Sue and stuck with her. “It must have been something to do with the Blockheads song,” he said.

Hit Me With Your Rhythm Stick by Ian Dury and the Blockheads went to no.1 in the UK in 1978. Chris would have been just two years old then. “I don’t remember asking for a rhythm stick, but I do remember the song. When you’re a kid, there’s a lot of fun in that song.”

Maybe his dad, Graham, or his older brother or sister, Matthew and Sarah, had it as a 7” single. Graham loomed large in Chris’s musical memories. Long before he picked up a guitar, he listened to The Beatles and The Shadows on his dad’s stereo.

Graham was a hi-fi buff, with a huge system. It was the tail end of the golden era of British hi-fi, when brands like Naim, Linn, Quad and Wharfedale ruled. His dad built his own speakers from kits and, when he was a teenager, Chris helped him. “I don’t think I would’ve gotten into music if it wasn’t for hi-fi,” he said. “I think if I’d listened to music on a little teeny radio, it might have really turned me off.”

Forget music, forget guitar – Chris Bird fell in love with sound itself.

He was inspired to play guitar by his uncle in the summer of 1988. His uncle was living on a narrowboat with his wife of the time, and Chris stayed with them. At night, they would sit on the boat, under the stars, singing and playing acoustic, and his uncle showed him how to play the basics.

He came back from his narrowboat holiday in love with the guitar.

He picked it up quickly, self-taught at first, and discovering the legends of guitar playing. Chris Bird was a 12 year-old Eric Clapton and Mark Knopfler fan. “I was terribly uncool in terms of what I was listening to,” said Chris. “I got into that level of sophisticated playing quite quickly.”

He was living in Shoreham, between Worthing and Brighton on the south coast of England. His secondary school was full of budding musicians and he met “two frankly incredible musicians.”

“My friend Gareth [Dylan Smith, the drummer] is an utter, utter genius in music,” said Chris. “He’s someone who thinks very much outside the box. To this day, I consider myself so lucky to have met him and played with him.”

His other bandmate was Steve Reynolds. “Gareth and I were substantially a few steps down from him,” said Chris. “He was just amazing. At first he was piano player, and then he took up bass as well. He had really poor eyesight, never had a driving license or anything like that, but he could play jazz. There’s was never a time when he wasn’t capable of jamming across an entire 8-octave keyboard.”

They started out as piano, drums and guitar – “It made for this weird concoction of non-music” – and did some gigs at school and for youth clubs who would put on shows in marquees on the Adur Rec in Shoreham. “Shoreham was a strange place back then,” he said. “There were just so many bands.”

His parents divorced when Chris was around 13 (“I was okay, though,” he said. “It wasn’t too bad”). He took A-Level music, and his school had a 24 track reel-to-reel recording system. So Chris and his band would record music on it as part of their course work.

He already had a bit of background experience. His mum’s second husband, Gordon, had a Tascam cassette recorder and some PZM flat mics, and he and his band messed around with those, jamming in their living room. Gordon knew computers and when Steve Reynolds got the Roland U-20 synth, they would sequence stuff into the computer.

They were just tooling around, learning through experimentation. “I spent an enormous amount of time learning how to improvise,” said Chris. Their parents let them jam in their garages, and his uncle threw house parties where everyone would join in. The stuff you learn doing that, you can’t possibly learn when you’re being schooled,” said Chris. “It leaves gaps in your knowledge but at the same time, it teaches you this level of free-ness of playing. It’s brilliant.”

And some new music was finally fighting for his attention. “I really loved the grunge stuff,” he said. “I think it was because it suited the fashion of the time – the bands looked like all my friends.”

He took classical lessons for a year or two, did early grades, and then took Music for GCSE and A-level. “I had a mix of knowledge. But that pre-formal bit of completely finding my way and just experimenting – the value in that. I’d put it above most of my school learning, almost. Almost.”

It was a different time for young guitar players, with few guitar magazines or no internet. Guitarist magazine was aimed at slightly older, more serious players. Official tab books were often inaccurate. “Some of the guitar books back then were really shit,” said Chris. He remembered buying the official book for Extreme’s Pornograffitti. “It was awful. Rubbish. Those books didn’t start getting good ’til probably the mid-90s.”

Total Guitar launched in 1994, and a local band in Shoreham managed to get a song on one of the magazine’s early CDs. (As well as backing tracks and gear demos, the free covermount CD would showcase some new music and unsigned bands.)

“I remember reading the early issues of Total Guitar and Guitar Techniques,” said Chris, “but they weren’t around until ’94 and I was already 18 by then.”

His brother Matt was another musical influence. Born in 1971, Matt was a big music fan. Chris remembers him listening to stuff like the Sisters of Mercy and Fields Of The Nephilim – goth/alternative rock borne out of the post-punk scene.

“I was surrounded by music that I wouldn’t necessarily have found or chosen,” said Chris. “In many respects, Matt had a wider taste in music than I did – and more of a voracious appetite to discover it.”

In his later teens, Matt began roadie-ing for a Brighton folk rock band called Altogether Elsewhere. “We were living in Sussex when the Levellers were starting to get big, and that was just a huge whole folk scene along the south coast.” Matt took Chris to some Altogether Elsewhere gigs. “You’d see a whole room of total hippies descend into total madness when they came on. Brilliant fun.”

When he left school, Chris went to University of Wolverhampton where he did an unlikely joint degree: Philosophy and Popular Music. “It’s the weirdest degree you can ever have,” he said.

It would be equally weird to imagine you could ever get a job out of it – and yet that’s exactly what he did: “I actually ended up using both of those things: writing thoughtful stories about artists and musicians, and teaching about popular music and how it works.”

University was also the beginning of another unlikely period: Chris Bird, The Punk Years. “One of my best mates, Ben, was a punk fanatic,” said Chris. “He got me into US punk.” Ben was promoting on the Birmingham punk scene, Chris helped out a little and they formed a band.

Ben played guitar and needed a bassist. Chris said, “Sure, man.” The band was called Seal Club. (Ben later formed the equally brilliantly-named Crap Shags.) They lived in a massive detached house with huge rooms and spent their days jamming. “I think we probably did 30 or 40 gigs, all original material. A lot of it was just Oi! punk.”

They did a load of gigs with Brummie punks Eastfield, who are still going now. It was the time of Rancid, Green Day, the Offspring and the ska punk explosion: No Doubt, Less Than Jake, The Mighty Mighty Bosstones. “My mates were big into ska punk,” said Chris. “It was all new to me, so I was just playing whatever. With ska punk, I might do a little bit of slap, you know, or it might just be crude down strokes. I got the hang of it pretty quickly.”

Some of those US punk bands had great bass players: Rancid’s Matt Freeman, Karl Alvarez of the Descendents. “All far better than me,” said Chris, “but I tried to assimilate some of that stuff. We didn’t have very straight punk sensibilities.”

In his living room in Chippenham, the Precision Bass remained in its flight case. Chris’s throat was dry. He was always softly-spoken, but the cancer, or the treatment, gave him a dry throat and reduced his voice to a husk. To soothe it, Sue brought him an ice lolly and made his guest a cup of tea.

He wanted to talk about a difficult period.

“I’ve had various dalliances with illness in my life,” he said.

It was when he was at university, and playing with Seal Club, that he experienced “a bout of ill health.”

ME (Myalgic Encephalomyelitis) is also known as Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and defined by the NHS as “a long-term condition that can affect different parts of the body. The most common symptom is extreme tiredness. The cause of ME/CFS is unknown.” In the 90s, ME was often dismissively referred to as “The Yuppie Flu,” as though it was hypochondria or the result of stress-related burnout. “I got it after a really nasty virus,” said Chris. “So it would have been a flu – but I was no yuppie.”

The medical establishment is still debating whether ME is psychological or physiological. Chris wouldn’t care to guess either way, but something was stressing him out.

He was gay and he hadn’t told anyone.

“I was in the closet at that time,” he said. “I didn’t come out until my mid-20s, which was a bit more normal back then. These days, kids come out in school.” He’d recently spoken to one of his old schoolmates and the two of them realised that – of the 1,200 people at their secondary school – neither of them knew a single person who was gay.

“So I don’t know,” said Chris. “Maybe depression was a part of it.”

He suffered from ME for around three years and it subsided around the same time as Chris began using a new medication for his epilepsy. “But maybe that epilepsy medication acted in a similar way to an antidepressant,” he said. “I don’t really understand what made it stop. But it did – and then I got the hell on with my life.”

Epilepsy. It had started when he was 13. He took medication for a few years, let it slip for a bit, and then made it part of his daily regimen: “And that’s when it seemed to make the ME go away.”

“The last time I had a seizure was either 2012 or 2010,” he said. “I have a driving license, have had for a long time, and it’s completely stable, so I’m lucky enough not to have to worry about it.”

It was around 2000 when he finally felt over it. “And that’s when I was able to really focus on music, post-degree. I joined a gym, got fitter, and a couple of years later, I was a guitar teacher.”

The illness had forced him to drop out of university for a bit, but he stayed in Wolverhampton, gigged with Seal Club, and then returned to his course around 1997, where he balanced his punk bass playing by hanging out with some great guitarists who were doing pure music degrees, and trying to pick up as much as he could. “Two players I remember in particular: Adam Dunn and Ian Alan. Just really, really talented people to be around.”

In 1999, his sister Sarah died, aged 26. Sarah had been disabled all her life. She was born with hydrocephalus – aka “water on the brain,” a buildup of fluid that exerts pressure and damages the brain – and she also suffered from epilepsy. “She was a bit of a medical miracle, my sister,” said Chris. “At one point, she had brain surgery something like nine times in 18 months. She lost a large part of her brain, just having it chopped out and stuff, and then her skull started to grow in and crush her brain.”

Sarah died of an epileptic seizure one night. “But it was peaceful,” says Chris. She was in hospital, being cared for after an infection, and just didn’t wake up one morning. “That was as peaceful an ending as we could have hoped for – and a life lived longer than we could have hoped for.”

After university, Chris Bird didn’t really know what to do. He toyed with the idea of doing law for a while (“There’s a parallel between law and music: There’s an interpretive nature and, if you’re a schooled musician, there’s a very formal nature”) but he decided to do another music course, at the ACM in Guildford.

“They had just opened up in their biggest new building, and all the guitarists who are now famous through the guitar mags were in the school that year: Guthrie Govan, Dave Kilminster, Eric Roche, Pete Callard, Jamie Humphries, all those guys.”

He loved it. He and a mate formed an acoustic duo, doing covers – making good money – and he did that for a couple of years.

“What you got from a place like ACM at that time, was a level of direction,” he said. “I’d just done a degree, but it was pure music, they didn’t give you much career advice. Whereas at the ACM in 2000, they’ve got connections to record companies, opportunities to try out for bands – and that’s what seemed like an opportunity to me.

“In the end, I just became a guitar teacher for a few years.”

Around this time, he said, “I became a bit of a fingerstylist.” He lost interest in electric guitar and focused instead on finger-style acoustic. What inspired that?

“Eric Roche and Clive Carroll.”

Eric Roche was an astonishing acoustic player who was appointed Head of Guitar at ACM the same year that Chris joined. His percussive style – where he’d tap rhythms on the body of his acoustic while playing – was legendary, as were his performances, which often culminated in extraordinary solo arrangements of pop and rock hits like Van Halen’s Jump or Smells Like Teen Spirit.

Eric Roche died in 2005, aged 37, from throat cancer.

“I had lessons with Eric,” said Chris. “It was one of my reasons for going there that year. My eternal claim to fame is the first exercise we did with him was a stretch down the fretboard and – because I was fairly tidy technically at that point – I got all the way down to the bottom of the fretboard with him, and nobody else in class did.

“But that,” he stressed, “is the sum total of any comparison I have with Eric.”

It was Clive Carroll’s playing that really bewitched him. Acoustic Guitar magazine once called Clive “…the best and most original young acoustic guitarist/composer in Britain”. Guitar Techniques called him “the acoustic Guthrie Govan.”

“Clive Carroll’s style utterly, utterly amazed me,” said Chris. “His album, The Red Guitar is, to my mind, possibly the finest 45 minutes of unaccompanied acoustic guitar music ever recorded. It’s insane.

“He writes music away from the guitar and then transposes it onto the guitar – and that makes for enormously complex music. He’s writing a bass line and melody line, and always finding something in the middle as well, and getting them to sit in a less guitaristic way.

“He’s following fewer patterns, because he’s already got it on paper, and he’s trying to make the paper [the written music] fit the guitar, rather than relying on shapes he knows on the guitar. He’s a total virtuoso.

“If you start with a shape, that’s where you’re gonna go. And that’s what an awful lot of guitarists do. They’ll have a shape, or a few shapes – maybe a lot of shapes – but ultimately, they’re led by muscle memory and the shapes that their fingers remember. This is where Clive leaves all that behind. His music’s just on another level.

“If you you compare him to Tommy Emmanuel: Clive will call Tommy ‘the Governor’, and you can see why – Tommy is an incredible player – but he’s playing very much more within the box. Clive is just a whole other world. I’d never heard anything like it and I really haven’t since, either.”

Chris sat in on a few masterclasses with Carroll, and would watch him live whenever he could. He became fascinated by fingerstyle. “Fingerstyle is like the piano,” he said. “You’re trying to put together multiple voices, in a way that I’m sure some people do on electric – but not really.”

In 2002, more tragedy: Graham, Chris’s dad, died alone in bed from a heart attack. Chris didn’t talk much about that.

He moved to Brighton and became a full-time guitar teacher and – at the age of 30 – made himself a five-year plan. It had one real goal: By the age of 35, he’d be writing for the guitar mags.

“I’d spent the best part of 20 years, working on my playing, getting better, studying, being around amazing musicians, different ways of learning from improvising, more scholarly learning. So I was like: ‘Oh, you’re starting to get good. You’re not Steve Allsworth yet, but you’re only 30. 35 is a reasonable goal for you to be writing tutorials for the mags at a really good level.’”

And then – just like he’d willed it into being – a year later, a little bit ahead of schedule, The Job came up.

Total Guitar’s Music Editor, James Uings, was making a sideways move on to website MusicRadar and Total Guitar were looking for a Music Editor.

He couldn’t quite believe it. He was only one year into his five-year plan. He didn’t think he was good enough to do the tutorials, but he knew he was good enough to do the sheet music, the proofreading, to commission lessons and come up with ideas. He told himself: “There’s no way you’re not applying for that.”

The application consisted of two things: One 150 word album review. Simples. The other? Not so simple: A fully transcribed and recorded song of your choice.

You had to submit both of these things to Jason Sidwell, the Senior Music Editor, who worked across Total Guitar, Guitarist and Guitar Techniques. Jason would vet the transcriptions and recordings, and – if the playing and the notation was good enough – the successful candidates would be brought in for an interview.

Chris did his transcription without consulting any another sources. “So there will have been mistakes – no doubt about it,” he said. “I could have just ripped off someone else’s, but I wanted to say: ‘That is my work. 100%.’”

The song he chose was Nutshell by Alice In Chains, from their Jar Of Flies EP, and once voted one of The 10 Saddest Songs of All Time by Rolling Stone readers. “It’s primarily acoustic, with some really nice electric over the top,” said Chris. “It’s a relatively simple song, but I knew Jason would get it because – even if you’re doing a transcription of an acoustic song – there is an expectation in these magazines of absolute accuracy.

“And that means getting every single strumming rhythm right. It takes bloody ages to go through 80-90 bars of music and make sure every strummed rhythm is correct, every single amount of strings is correct – that you’re strumming five strings, not six strings or whatever. And I knew Jason would get that.”

It took him three weeks to transcribe and record the full song to the standard he was happy with.

He was interviewed in Bath by Total Guitar Editor Stephen Lawson.

He got the job.

We could finish this story here, with a happy ending. We could talk about the good times he had working with Stephen Lawson and Deputy Editor Claire Davies.

We could skip forward to when Stuart Williams became Editor and, says Chris, kicked off “a new golden era for the team,” with Rob Laing as Content Editor (Rob later became Editor of TG, and is currently Reviews Editor of Guitars, across Guitar World, MusicRadar and Guitar Player), and Michael Astley-Brown as Reviews Editor (Mike is now Editor In Chief of Guitarworld.com).

We could talk about how the four of them formed a covers band, playing grunge classics, called Ratbush, and why the band was so-named: When the bushes at the front of Future’s headquarters in Bath, Quay House, were cut down, the rats that lived in the bushes re-homed themselves in the basement of Quay House – and then got into the ventilation system and died. The whole building stank for months.

Hence: Ratbush. The band was eventually and officially known by the more professional name, The Seattle Revival. No-one wanted a band called Ratbush to play at their birthday party

They had Editorial meetings down the pub, and went to see bands together. Chris got to work with guys he’d looked up to for years, like Steve Allsworth, and he interviewed legends like Joe Satriani, Steve Vai, Brian May, Jimmy Page and many others. “Steve Vai is every bit the wizard you think he’s gonna be,” said Chris. “He really does have that kind of insightful magic about him. Tommy Emmanuel is another great talker. You just get so much insight from somebody like that.”

In 2009, he bought an iMac, switched from PC to Mac, from Cubase to Logic, and did a Logic course at Bath City College, where he met a guy called Adrian. Adrian was in a romantic partnership with a guy called Adan. They were both songwriters and Chris became really good friends with them and started working with them on some songs. Over a four year period, they wrote and recorded 80 or 90 songs, initially under the name Electrolyze and then Sea Of Flowers.

“Adrian and Adan are wonderful people, but they would be firing off at all different directions, with me kind of trying to rein them in. Adrian’s idea was to try and be as broad as possible do loads of different songs. Adan was more of a lyricist. It was one of the one of the most fun times of my life.”

Some of their tracks sound like REM, others like Fleetwood Mac or Coldplay, some are disco and R’n’B. “I feel like we could have been jobbing songwriters,” said Chris. “We just didn’t have the discipline between the three of us.

“I think you make the best music with your friends, and we were good friends. Every project I’ve ever been in has been about the chemistry. We were so prolific. You just can’t expect an experience like that to come again.”

Sea Of Flowers has six songs on Spotify; Electrolyze, just one. The rest are unfinished, lying on various hard drives. Chris set up a Soundcloud at one point, called Unfinished Songs, to host them all. Unfortunately that was also an unfinished project. The only song on there is a track called The Funky Suicides, a “mental jazz” song that was the first thing he ever created on Logic.

Recently, Adrian sent Chris a new song, suggesting that maybe they could work on it together.

“I’m afraid you’re probably too late,” said Chris.

At the end of 2019, two months before the world went into lockdown, Chris became Editor of Total Guitar.

“Nobody knew the mag better than I did at that point,” he said. “We had some really good ideas for first 18 months of my editorship, and some good wins, with Jimmy Page and Brian May in particular.”

Chris’s interviews with Brian May and Jimmy Page were long and detailed – guitar hero heaven. But as well as his coverage of the legends, he brought a moden sensibility to the magazine. He was open-minded about the way that guitar is used in modern music – whether it was pop, or alternative, metal or whatever.

Some people in the industry have a habit of tuning their noses up at bands because “the playing isn’t good enough”. Not Chris.

“That attitude sucks,” he said. “It doesn’t just dismiss bands, it dismisses genres. What, let’s not do post-rock? Black MIDI, Squid? People play in different ways. If you’re just expecting someone to come along and either play pentatonics or be a virtuoso, then you’re substantially limiting the music you’re listening to.

“In the last few years, we’ve seen a real growth in guitar music and guitar techniques. Progressive metal has moved on, and that’s fantastic, just to hear something that feels fresh and new. Polyphia, Chon, even bands like Haken – all of that is technical.”

As well as the usual set of legends, the people he put on the cover of TG included Sam Fender, Polyphia, the Nova Twins, Yvette Young, Marcin, Matteo Mancuso, Tash Sultana, Carmen Vandenberg and more. Young, diverse, talented. It showed a love of music – of sound itself.

“It’s funny,” said Chris. “When people ask me what I listen to, I’ve never really been able to answer. I prefer the discovery of it. I love Spotify. I love it firing music at me.

“On Total Guitar, I liked recommendations from the people around me. Sometimes I trust other people’s recommendations more than my own. I’m more likely to go, ‘Yeah, Stan, this is brilliant! Mike, this is brilliant, love it!’ than I am with something I chose myself.”

In 2023, Chris’s brother Matt died, aged 52. After his time with Altogether Everywhere, Matt had become a DJ, made some of his own music, and promoted dance nights in Brighton and London. Somewhere along the line, he got into drugs, was rescued from a bad situation in Brighton and eventually settled in Torquay.

“He stayed there till the day he died,” said Chris. “He established roots – and established ways to get drugs. Where he died was not a nice place. He died with pretty much nothing.”

Matt died from sepsis. He had a fall, cracked a rib, and it went undiagnosed.

After Matt’s death, Chris discovered that the password on his phone was Sarah’s date of birth. Chris connected that to a traumatic incident when Sarah was 14 and Matt was 16. Sarah had a stroke, Matt found her and resuscitated her, and then called their dad for help.

“He carried that for his whole life,” said Chris. “He carried that, at some level, and he became a drug addict.”

Towards the end of 2023, Chris started to feel unwell. He couldn’t work out what it was. One night, after work, he walked from the Future office to the train station – possibly 200 metres – and had to sit down and rest.

He went for blood tests, had his heart checked out, and then – in April 2024, he got the news. He had stage 4 bowel cancer and it had spread to his liver.

He continued to work – was determined to – to keep busy, stay positive. Almost exactly a year after his diagnosis, they told him that his liver was too sick to continue with chemotherapy.

“You have months,” they told him, “but prepare for weeks.”

“My liver is so ill that I could get an infection and go quickly,” said Chris. “There’s also a chance that it might recover a little to give me that slightly longer prognosis – and of course I’m hoping for that. Not least because there’s a new Hives album out in August. My next job is to stop my mum from playing bloody Elbow at the funeral.”

In recent weeks, he’d found himself listening to an old favourite: Icelandic artist Ólafur Arnalds. “Beautiful,” he said. “He may well make an appearance at my funeral.” Chris was making a playlist of songs to be played at his own wake.

“It’ll be easy, because a funeral is 45 minutes long, and you get four songs, right, and I’ve already decided one. It’s more for, like, the pub and memorial afterwards. What I thought I might do is just ask all my friends to choose a song. Then everyone who turns up will hear a song they like.”

It was getting late. His living room in Chippenham was glowing orange. “I think we’ve spoken about everything I’ve ever done, musically,” he said. “It’s been a lot of fun.”

There was loads they hadn’t talked about. They hadn’t talked about his dad much, or about coming out, or his long-term relationship with Simon, or his car crash last year, or about how he almost represented the UK at judo in the Commonwealth Games when he was younger.

But maybe there was still time.

“I don’t know what I’m going to do with this,” said his guest. “But I don’t want it to be your obituary. Let’s work on it together. I’ll write it up and send it to you and we can go back and forth on it. There might be some bits you’ll want to add or take out.”

“Yeah,” said Chris. “And then after I’m gone, you can just add a footnote. ‘Chris Bird died on blah blah blah.’”

“Yeah.”

It was a hard thing to talk about.

“Yeah, I’m sure we can do that.”

Chris Bird died in hospital, a week after this interview, on 27 May, 2025.