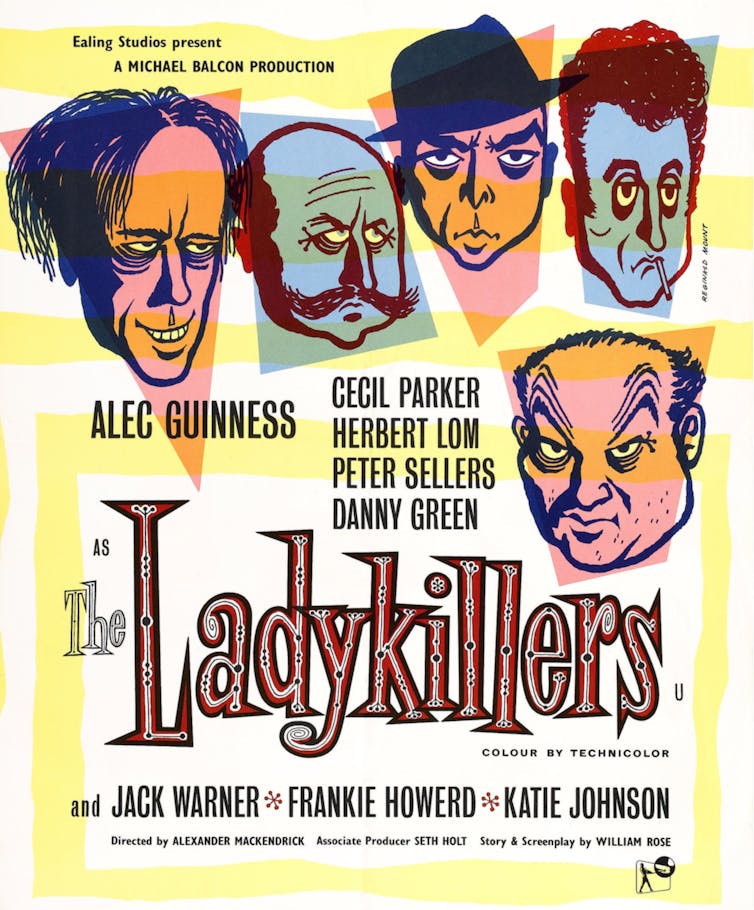

Mrs. Wilberforce (Katie Johnson) lives alone in a rickety Victorian house near London’s King’s Cross railway station. She rents a room to Professor Marcus (Alec Guinness), who claims to be a musician, and asks to use the room for practice sessions with his string quintet.

But wait. Professor Marcus and his four associates are in fact plotting an armed robbery and plan to use Mrs. Wilberforce in their dastardly scheme.

What a pleasure it is to revisit The Ladykillers (1955) – a jet-black, peculiarly subversive marriage of genteel English manners and anarchic criminality.

With its cast of eccentrics, dry wit and distinctively British whimsy, this film from London-based Ealing Studios perfectly zig-zags between kind-hearted and creepy. And 70 years on, it is fondly remembered as the closing flourish of the golden age of Ealing comedies.

A comic institution

Ealing Studios, based in the west London suburb of the same name, was founded in 1902, making it the world’s oldest continuously running film studio.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, under the leadership of Michael Balcon, the studio became known for producing a series of comedies that reflected British values, class tensions and post-war anxieties, often in a light-hearted or ironic way.

Films such as Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949), Passport to Pimlico (1949) and The Lavender Hill Mob (1951) portrayed a particular brand of British humour: ironic, restrained and, above all, socially observant.

These films gently poked fun at the British class system while celebrating quirky individuals and tight-knit neighbourhoods. As Balcon himself later said:

We made films at Ealing that were good, bad and indifferent, but that were indisputably British. They were rooted in the soil of the country.

Earlier successes depicted criminal protagonists whose schemes were both ingenious and only slightly morally dubious. The Ladykillers took this tradition to its logical extreme: the criminals were no longer charming anti-heroes, but grotesque figures, hapless in their execution of the robbery.

The film’s delicious central irony, in keeping with the Ealing ethos, is that the one person capable of undoing the criminal plot is the least likely: a frail old woman with a kettle and a parrot.

Making a masterpiece

The Ladykillers was written by William Rose, who allegedly dreamt the plot and awoke to write it down. This dream-like provenance makes its way into the film.

Scottish-American director Alexander Mackendrick, who had previously worked for Ealing on Whisky Galore! (1949) and The Man in the White Suit (1951), gave the film its distinctive atmosphere of part-grotesque fairy tale and part-suburban farce. As Mackendrick once remarked

the characters are all caricatures, fable figures; none of them is real for a moment.

Mrs. Wilberforce’s house, where most of the action is set, was constructed on an Ealing backlot – a convincing reminder of the sooty urban geography of post-war London.

Prague-born cinematographer Otto Heller used shadow and deep contrast to lend a macabre quality to a comedy that often flirts with horror. A perfect example is when Mrs. Wilberforce opens the door to the professor for the first time.

Alec Guinness’s performance is a revelation. His waxen features, exaggerated false teeth and vulture-like gestures are a far cry from Obi-Wan Kenobi and George Smiley. He turns Professor Marcus into a grotesque parody of a criminal mastermind.

Guinness is abetted by stalwarts such as Herbert Lom and Danny Green. And Peter Sellers gives a nervy performance as Harry, in a role that would mark the beginning of his rise to Hollywood stardom.

A profoundly moral tale

Professor Marcus and his band of misfits mock the pretensions of criminal sophistication, contrasting them with the quiet rectitude of an old woman who represents a vanishing Britain.

They brilliantly capture the contradictions of 1950s London: the post-war optimism laced with paranoia, social deference mingled with subversion, and a genteel facade barely concealing the chaos beneath. It’s little wonder some critics see this Ealing output as deeply political.

Without spoiling the plot, The Ladykillers concludes with a restorative, comic sense of moral order. The criminal enterprise collapses, not due to law enforcement or clever detection, but because of the gang’s own ineptitude and Mrs. Wilberforce’s stubborn innocence and moral clarity.

A beloved film, then and now

The Ladykillers was a critical and commercial smash in the United Kingdom. Critic Penelope Houston applauded its “splendid, savage absurdity”. It was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay and won Katie Johnson a BAFTA for Best British Actress, aged 77.

The film was remade by the Coen Brothers in 2004, this time with Tom Hanks as a Southern gentleman crook. But this version was widely panned, illustrating just how specific the tone of the original was.

Its reputation has only grown since December 1955, with the British Film Institute ranking it among the best British films of the 20th century.

At one point in the film, Professor Marcus cries out

We’ll never be able to kill her. She’ll always be with us, for ever and ever and ever, and there’s nothing we can do about it.

Just like the stubborn, indomitable spirit of Mrs. Wilberforce, The Ladykillers isn’t going anywhere.

Ben McCann does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.