1) Von Cramm goes close, 1937

Fred Perry’s final victim at Wimbledon had an eye-catching name but there was far more to Baron Gottfried von Cramm’s story than his outstanding moniker. Born into nobility in 1909, Von Cramm was one of the finest tennis players produced by Germany, a champion, an aristocrat with an Aryan appearance and a strident opponent of the Nazis. He was a man consumed by a burning sense of fair play and honour. He lived a full life.

Money and status were not his motivations. He loved tennis and in 1932 he formed a formidable doubles partnership with Daniel Prenn, a Jewish refugee from Russia. However Prenn fled to England after the Nazis came to power in Germany in 1933 and Von Cramm was left to try his luck as a singles player. He flourished, picking up his first title by winning the 1934 French Championships, beating Perry in five sets. He won it again in 1936 and was a losing finalist three times at Wimbledon, succumbing to Perry in 1935 and 1936 and to Don Budge in 1937.

The Nazis sought to capitalise on Von Cramm’s sporting prowess, but he loathed them and rejected their overtures to join the party. “Hitler?” he said. “He’s nothing but a house painter.” Hermann Göring, founder of the Gestapo, went to great lengths in his efforts to change Von Cramm’s mind, tearing up the mortgages that were held by Jewish banks on Von Cramm property. “Now you are free,” Göring said.

“One more reason not to join you,” Von Cramm replied.

He became a target for the Nazis. The Gestapo were after him and he was arrested in 1938. His crime was a past homosexual relationship with a Jewish actor called Manasse Herbst, who was now living in Palestine. He was actually married twice, first to Lisa von Dobeneck before the war and then to Barbara Hutton, the American socialite and Woolworth heiress, 10 years after it ended. Hutton, dubbed the Poor Little Rich Girl, had an alcohol and drugs problem and the couple divorced in 1959.

Von Cramm was accused of immoral behaviour in court – the judge called his relationship with Herbst a “perverse compensation for an unhappy married life” – and Von Cramm was sent to Lehrter Strasse prison in Berlin. He was released in 1939 and attempted to continue with his career.

He was one of the best in the world in 1937. Perry had turned professional and was thus excluded from playing at Wimbledon, so another all-time great rivalry developed. Budge beat Von Cramm in the Wimbledon final. They met when Germany played the USA in the inter-zone final of the International Lawn Tennis Challenge (now the Davis Cup) and Budge won a famous match in five gripping sets, fighting back from two sets down.

Von Cramm always seemed to come up short. They met in the final of the US Open in 1937 and Budge won 6-1, 7-9, 6-1, 3-6, 6-1.

There should have been more classic battles. Instead the Gestapo intervened, Von Cramm’s career was put on hold and by the time he returned, Budge had also turned pro. Not that Budge forgot him: he led other American athletes in putting pressure on the Nazis to release Von Cramm while he was in prison.

However, Budge’s absence from the amateur circuit did not open the door for Von Cramm; instead it was slammed shut in his face. He ruled at Queen’s in 1939, but he could not play at Wimbledon because of his criminal record (Wimbledon officials argued that he had not applied to enter the tournament) and he missed the US Open after he was denied a temporary visa.

The war began, Von Cramm was drafted, injured and awarded the Iron Cross – and then in 1944 he was arrested again, accused of being part of the plot to assassinate Hitler. Yet he survived the Gestapo’s interrogations and spent the rest of the war in Sweden, where he was given refuge by King Gustaf V. When he returned to tennis after 1945, his best years were behind him.

For more details about Von Cramm’s life, check out this article in The Scotsman from 2009.

2) A Gallic affair, 1926

The aforementioned King Gustaf V was a keen tennis fan – he liked to play, using the pseudonym Mr G, and once shared a court with the legendary Suzanne Lenglen – and Von Cramm was not the only player who benefited from his help during the war. You’ve got to love the monarchy!

But first, some scene setting. For the first 36 years of the US Open, the men’s singles title was won only once by a non-American, Britain’s Laurence Doherty in 1904, and there was always at least one home favourite in the final. Yet that changed when the 1926 final was contested by two Frenchmen, René Lacoste beating Jean Borotra, who was born on the French side of the Basque country, 6-4, 6-0, 6-4.

They were fine players, part of the dominant French generation who were revered as the Four Musketeers, Jacques Brugnon and Henri Cochet making up the rest of the gang. Lacoste won three French Opens, two Wimbledons and two US Opens, Borotra not far behind with two Wimbledons, an Australian Open, a French Open and a superb record in doubles and mixed doubles. Borotra was known as the Bounding Basque.

Then came the war. France fell to the Nazis and although Borotra took a job in the Vichy regime as sports commissioner in 1940, he fell out of favour with the Germans and was sacked in 1942. He decided to join the opposition – and was soon whisked away by the Gestapo and sent to Sachsenhausen, a concentration camp near Berlin.

In came King Gustaf, thanks to some prodding from one of Borotra’s fellow Musketeers, Lacoste. The king intervened, Borotra was transferred to the Itter Castle in Austria and as it became clear that the Allies were winning, he escaped through a window, evaded the guards and brought American troops back to the castle. That’s good musketeering.

3) Clijsters returns, 2009

It is not easy for female athletes to combine their careers with motherhood and for Kim Clijsters, tennis’s loss was her family’s gain when she retired in 2007 because of injuries. She was only 23 and had already won the US Open in 2005, winning in the final against her fellow Belgian, Justine Henin, another who put down her racket too soon. “To retire before the age of 24, it is very young but it was so beautiful,” Clijsters said. “Money is important, but not the most important thing in my life. Health and private happiness are so much more important.” She gave birth to her first child in early 2008.

However, she did not take to retirement and ended her two-year sabbatical a month before the 2009 US Open. Surely she could not regain her crown? It seemed a stretch. But they do say that mum knows best and despite her lack of match sharpness, Clijsters had the class to fight her way through the draw and into a semi-final against Serena Williams. Surely she would meet her end here, against the No2 seed? Think again. Williams was outplayed and her emotions got the better of her when she was given a point penalty for a verbal tirade at a lineswoman when she was match point down.

Clijsters was into the final and there was no stopping her now: Caroline Wozniacki was dispatched 7-5, 6-3 in front of a disbelieving New York crowd and Clijsters was holding her little daughter, Jada, when she gave her post-match interview on court. “We tried to plan her naptime a little bit later so she could be here today,” said Clijsters, who won another US Open title and the Australian Open before retiring again in 2012. “It’s the greatest feeling in the world, being a mother.”

Has there ever been a better comeback?

4) Serena beats Hingis in 1999

Martina Hingis was not to know it, but she was playing a dangerous game when she said that the Williams family had big mouths. Richard Williams, Venus and Serena’s father, had predicted at the start tournament that his daughters would meet in the final and Hingis, the top seed and reigning Australian and French Open champion, was less than impressed. “They always talk a lot,” she said. “It’s more pressure on them. Whether they can handle it or not, now that’s the question.’’

And the Swiss prodigy had a point. Only 18, she already had five majors in the bag, winning the first of them when she was 16, and could be forgiven for her dismissive tone. Little was she to know that there is a price to pay for getting on Serena Williams’s nerves. “She’s always been the type of person that … says things, just speaks her mind,” Williams said. “I guess it has a little bit to do with not having a formal education. But you just have to somehow think more; you have to use your brain a little more in the tennis world.”

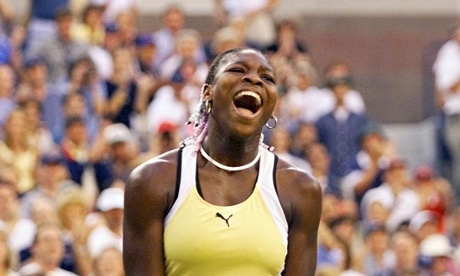

Big words from a 17-year-old who was yet to win her first grand slam. Yet that was about to change, even though her father’s prediction did not quite come true. Serena got to the semi-finals and beat the defending champion, Lindsay Davenport, 6-4, 1-6, 6-4, but Hingis saw off Venus in three sets in the other semi. Now for little sister.

Yet Serena had other ideas. She was inspired, winning 6-3, 7-6. It was the start of a new era. “She was the player I least liked to play against,” Hingis told the Guardian recently. “It was hard to read her serve and she came up with the best when she was down, with danger.” Sixteen years later, Williams has won 21 grand slam singles titles and counting, 16 more than Hingis.

5) Graf beats Sabatini, 1988

Williams is chasing history at Flushing Meadows. You might have heard that she is on the verge of becoming the first player to win the calendar slam for the first time since Steffi Graf held all four majors in 1988. Not only that, but victory will also see Williams equal Graf’s record of 22 grand slam singles titles in the Open era. “I remember above all the extreme fatigue I felt in New York,” Graf said. “I was feeling the expectation around me that wasn’t mine and that was becoming suffocating. It was terrible.”

And the final against Gabriela Sabatini was far from straightforward. Graf won the first set 6-3 but she wobbled and let the Argentinian teenager back into the match. Sabatini won the second set 6-3. Yet few players had the German’s awe-inspiring mental toughness and she roused herself in the decider, winning it 6-1.

“I think it is great what she did,” Sabatini said. “Not too many people can win a grand slam. She won all with much confidence. Her mentality is perfect.” Williams will need to match the coolness that German teenager had 27 years ago.

6) Lendl breaks his duck, 1985

Just like that scowling chap he coached for a couple of years, Ivan Lendl lost his first four grand slam finals. He lost in the final of the French Open in 1981 and 1983. He lost in the final of the US Open in 1982 and 1983. He finally got the monkey off his back at Roland Garros in 1984, but more misery awaited him at the US Open in 1984 and the French a year later. Normal service was resumed and his record in the US Open, three consecutive defeats in the final, haunted him. Jimmy Connors was his tormentor in 82 and 83, John McEnroe in 84, and the American supporters lapped it up.

Lendl was made out of granite and his revenge, a 7-6, 6-3, 6-4 victory over McEnroe in the 1985 final, was sweet. “I’m just so happy I’m not even going to try and describe it,” Lendl said. “I have been through it so many times that I just say to myself: ‘Keep trying,’ as I did last year in the French. I said: ‘Keep trying. One of these days you have to get it.’ Not too many people expected me to win. I had only to gain. If you asked me two weeks ago, I would have said I’d take it over my grandmother.”

Lendl’s iron will lifted him to the next two US Opens as well, a triumph of spirit, ability and unstinting stubbornness, and his refusal to give in should be an example to anyone who has struggled to overcome the pain of failure.