It's hot, humid and thunder rumbles threateningly around nearby hills. A river of sweat runs down my back and between plucking blackberry thorns out of my socks I swat swarms of blood-thirsty mosquitos.

To say conditions are far from comfortable would be an understatement. But I wouldn't want to be anywhere else, for I'm about to witness one of our region's most captivating wildlife spectacles - the nightly fly-out of the aptly named eastern bentwing bats (Miniopterus schreibersii) from a cave squirrelled away in the hills of Wee Jasper.

While the exact location of the far-flung cave, one of only three large maternity caves in NSW and a handful in the entire country, is kept top secret, one man who has observed the phenomenon hundreds of times is NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service Ecohealth team leader Dr Doug Mills.

Doug has been studying the cute (yes, bats can be cute too, can't they?) chocolate-coloured microbats, which are about the size of a mouse, for the best part of two decades, including monitoring this remote site now for 15 years.

And despite the near-nightly pothole-ridden drives from Canberra each summer he "never tires of it" - "It still impresses me every single time I come out here".

"It's wonderful to see the bats fly out, it's incredibly special," he explains as he leads me through thick scrub, and more mozzies, up towards the mouth of the cave.

Not that you'd really know it was a cave. It's more a tiny opening in the limestone outcrop, barely a couple of metres wide.

"With just one small exit, only one species using it and ease of access, it's a near perfect place to research these microbats," explains Doug, adding "it's incredible to think that at this time of the year there are likely hundreds of pups [babies] per square metre of cave ceiling".

While Doug starts his routine of setting up his monitoring gear overlooking the mouth of the cave, I plonk myself on a limestone pillar and smother myself from head to toe in another layer of insect repellent. The natural spectacle is supposed to be the bat fly out, isn't it? Not an Akubra-clad columnist being eaten alive by a swarm of mozzies.

The mosquitos don't seem to worry Doug. He's too focused on the task at hand. Over 15 years, Doug has refined a highly specialised thermal video monitoring survey technique that is now being used to monitor bat colonies in other parts of Australia.

"We use thermal imaging and software designed by the US military to record the bats entering and exiting the cave each night," he explains showing me his camera screen, which "will soon fill with hundred hundreds of flashing red dots, each representing an individual bat."

"This technique allows me to quickly and accurately count the population and get a better understanding of breeding success as well as the timing of weaning and migration," explains Doug, who admits he also does a manual count to help validate the software as required.

Just as dusk turns into night, as if on cue, we hear a muffled commotion emerging from the direction of the cave. It's the frenzied flapping of wings. Each bat jostling for position in preparation for their nightly exodus to forage for food.

"You won't see the first few, but you'll hear them," advises Doug.

And, of course, he's right. First, I feel one whoosh by my cheek, then two. Then before long, they are flying out at several hundred per minute. Thankfully I don't need to duck or weave - the bats with their inbuilt echolocation navigation systems are experts getting out of my way.

"As a specialist insect-eater, these bentwing bats provide important ecosystem services with individuals capable of consuming their own body weight in insects [bugs and moths, sadly not mozzies...] every night," reveals Doug.

Wow! If that's not justification for the burger with the lot I woofed down on the drive out through Yass, then what is?

When I ask Doug how the population is faring, despite the veil of darkness that has now enveloped us, his face lights up.

"After their numbers were smashed by the long drought culminating in the Black Summer fires, there's been a dramatic increase in numbers," he reveals, adding, "the population inside the Wee Jasper limestone caves is now 17 per cent higher than the long-term average."

This is great news, especially on top of similar post-Black Summer bouncebacks of populations of bogong moths and spotted-tailed quolls also recently exclusively revealed in this column.

"The higher-than-average rainfall over the past two summers has had an obvious positive impact on this population, and their recovery is astonishing," he explains, adding "the same population declined by one-third, or around 7000 bats, in the years preceding the Black Summer bushfires, so we are thrilled to see it not only bounce back but thrive," Doug says, still smiling from ear to ear.

"This most recent data indicates that bentwing bats are capable of recovering from short-term declines and provides a better understanding of how the species is tracking across its entire range," he explains.

It's wildlife warriors like Dr Doug Mills that dedicate years of their life to understanding a single population of a species that are our true champions of the Australian bush. Now, if only he could somehow convince his bats to develop a taste for those pesky mozzies.

Postscript: The bat count came in at 21,160 +/- 613 bats. (And yes, I lost count at about 53).

Bat Facts

- Eastern bentwing bats can live up to 20 years.

- Each summer, tens of thousands of female eastern bentwing bats migrate up to 300km to large limestone caves in southern NSW to deliver and rear their pups. The females congregate here for the entire summer, leaving in autumn to disperse across the landscape.

- Although Dr Doug Mills would "dearly love" to venture into the Wee Jasper maternity cave, it's unlikely he, or anyone else for that matter, will for the foreseeable future. "Histoplasmosis [a fungal infection that can lurk in bat guano, and which left untreated can be fatal] infected a group of scouts here in 1972," explains Doug, adding, "since then, adventure cavers stay well clear of here, which is actually good thing for the bats".

- Banded bats from the Wee Jasper colony have been found as far afield as Eden and Gabo Island, off the East Gippsland coast in Victoria.

- The bats fly up to 30km a night to a foraging site.

- If it's raining, they will still fly out, but may not be as successful in foraging for insects as the rain makes it harder for the bats to echo-locate their prey.

- From mid-February, Doug will also count the pups as they join their mothers on their nightly foray for food.

- A NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service study of eastern bentwing bats is undertaken on the national parks' estate at two of three known large maternity colonies in NSW, highlighting the critical role of national parks in the effective conservation of threatened species.

- NPWS is the first national parks agency in Australia to commit to a zero extinctions target, and one of the first globally, and NPWS' Threatened Species Framework outlines a series of actions to meet its commitment of zero extinctions and to restore threatened species populations.

- For more information on eastern Bentwing bats, visit the NSW Environment website.

WHERE ON THE SOUTH COAST?

Rating: Easy - Medium

Clue: Monthly markets transform this hinterland village

How to enter: Email your guess along with your name and address to tym@iinet.net.au The first correct email sent after 10am, Saturday, January 28, wins a double pass to Dendy, the Home of Quality Cinema.

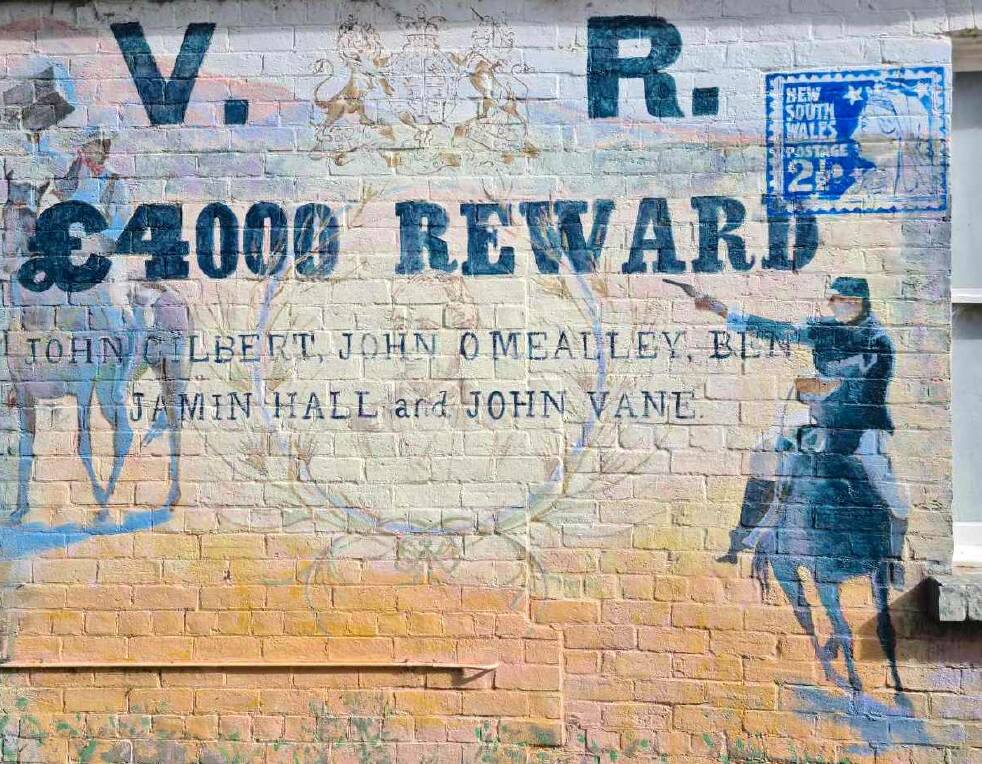

Last week: Congratulations to Jordan Gannaway, of Holder, who was first to correctly identify last week's location as part of the Gilbert Mural, on the side of the Old Produce Store (facing Pioneer Park) in Binalong. The mural tells the story of the shooting death of bushranger "Flash" John Gilbert by police, as told by Banjo Paterson in his poem How Gilbert Died. Jordan just beat a barrage of other correct entrants, including John Morland and Frances McGee, both of Curtin. Frances visited Binalong last year in between COVID lockdowns. "The shop in the old building sells locally made products, including some intriguing teas, but sadly was closed when I was there. The Bushranger Blend would have been top of my shopping list!" she exclaims.

MAILBAG

Singing Stones Duo

While Alan Hume, of Burrill Lake (formerly of Greenway in the ACT), was unaware of the Singing Stones Beach near Pretty Beach, he reveals "there is a very similar cove of singing stones just south of Pebbly Beach (appropriately named) and north of Depot Beach". According to Alan, who visited the remote beach often back in the 1990s with kids in tow, "it is easily accessed from either end at high or low tide". Meanwhile, several readers are perplexed as to who bestowed Singing Stones Beach its unofficial name to begin with - perhaps a mystery to tackle in a future column.

SIMULACRA CORNER

While on a summer stroll at Urambi Hill, Rose Higgins and family from Kambah stopped in their tracks at the sight of this tree. "It looks like an alien with two googly eyes," claims Rose.

._Patrick_s_Day_Parade_94380.jpg?w=600)