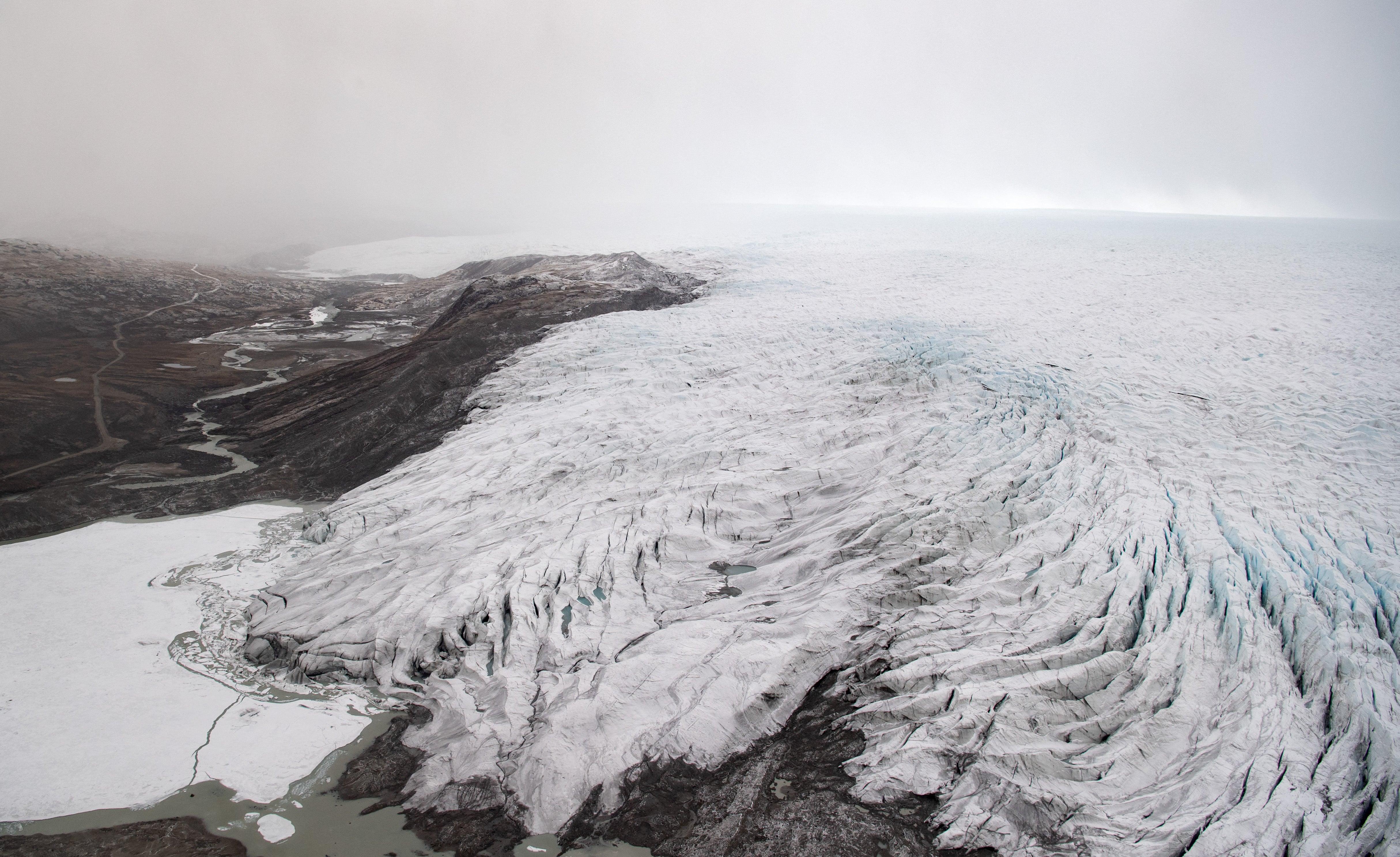

Greenland had a quite a year. For the first time in its history, rain fell at its summit. In August, it experienced one of the latest-occurring melt events in recent memory. This also became the third year with major melting events in the past decade.

By the end of the melt season, the ice sheet lost more ice than it gained – for the 25th year in a row.

“The long-term past two decades have shown us the incredible wrongness in calling ‘glacial pace’ something slow,” says Marco Tedesco, a research professor at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University.

Greenland lost a net total of 166 gigatons of ice from September 2020 through August 2021. Overall, this loss is on par with recent decades – but how it arrived at that final number is not.

“2020/21 was a comparably ‘normal’ year. The new normal, that is,” writes Martin Stendel, a polar researcher at the Danish Meteorological Institute, in an email. “But that does not mean it was good in this sense.”

The island experienced anomalous swings from intense melting to unusual snowfall from a former hurricane. While the annual snowfall accumulation was healthy, ice loss from iceberg calving and ocean melt was the highest since satellite records began in 1986.

Starting in July, Greenland experienced three notable melting events. Researchers reported that one episode triggered a significant loss of eight to 12 gigatons per day

“When we see instability like this, this switch from a lot of accumulation to a lot of melting to a lot of accumulation to a lot of melting, it's really a signal of the system that is looking for a way to be stable again,” says Tedesco, who also serves as an adjunct scientist at the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies. “The message of instability that Greenland is sending is terrible.”

This year's activity over Greenland has many researchers concerned for a not-too-distant future.

Scientists calculate Greenland's total mass losses and gains by accounting for several factors. For one, they look at the net accumulation of snow on the ice sheet's surface, known as surface mass balance, from when the first snowflakes fall (typically September) through the end of the melt season (the following August).

Winter snowfall was close to average this year, according to a summary by Stendel and his colleagues. Then in late June, a near-record amount of snow fell. Not only did the snow add mass to the ice sheet, but it also helped reflect sunlight back into the atmosphere and helped delay the first melt of summer.

But starting in July, Greenland experienced three notable melting events. Researchers reported that one episode triggered a significant loss of eight to 12 gigatons per day. Another episode in August also caused widespread melting, but it was perhaps more noteworthy because it occurred unusually late in the melt season as rain fell on the ice sheet's summit for the first time on record.

Overall, the ice sheet managed to gain 396 gigatons of mass due to snow from September 2020 to August 2021 – average for recent decades, although still significantly lower than in the 1990s.

However, mass increases from snow on the ice sheet's surface are only part of the story.

During the year, a large portion of ice is lost through the calving, or breaking off, of icebergs. Ice is also lost from relatively warmer seawater coming into contact and melting glacier tongues. (A much smaller proportion of ice is also lost through “basal melting”, which accounts for the heat flux from under the ice sheet as ice slides over the ground.)

This year, scientists calculated that around 500 gigatons were lost from iceberg calving and ocean melt – the highest in 35 years of satellite records.

Notably, the Jakobshavn Glacier (also known as the Ilulissat glacier) on West Greenland, the world's fastest-moving glacier, shed about 45 gigatons in the past year – particularly alarming considering it was growing recently. This calving accounts for about 10% of the total calving and ocean melt loss this year.

“The warmer ocean – together with the surface melt – is what really makes a glacier like that retreat and probably Jakobshavn got the double whammy this year,” ocean scientist Josh Willis writes in an email. Willis leads NASA's Oceans Melting Greenland project, and he conducted field research in Greenland this summer.

In the end, the high amount of ice loss from calving and submarine melting significantly affected the ice sheet's mass balance for this year. But it could have been worse had the surface mass accumulation not been so high. In 2019, low winter snowfall plus a warm summer resulted in a net ice loss of 329 gigatons.

The 2020-21 period “was not close to a record, which I'm very thankful for, but it was another year where we were, overall, losing ice and not gaining it on the ice sheet,” says Twila Moon, a researcher with the National Snow and Ice Data Center.

From September 1968 to August 2021, the Greenland Ice Sheet has lost around 5,500 gigatons of ice – equivalent to 1.5cm of global average sea level rise.

Climate change is a double-edged sword for Greenland. On one hand, as global temperatures rise, the amount of moisture in the air will increase and could lead to more precipitation – including more snowfall.

“You have an accumulation that is helping to mute the melting and help the mass of Greenland to gain a little,” says Tedesco. “But at the same time, it's something that we think is very connected to what is going to happen as part of global warming.”

Global temperatures will also induce more surface melting and melting from the ocean, with the losses outweighing the increases in snow accumulation, similar to this year.

“What we've seen, if we look at sort of longer-term trends, is that loss of mass from Greenland from increased melt and runoff from the summer would more than offset the increased accumulation that we would see,” says Tom Mote, a climate scientist at the University of Georgia.

Another concern is that the increased snowfall could change to rain as the climate warms. In recent decades, darker, wetter clouds have increasingly moved over Greenland, says Tedesco. This year, rain was prevalent across the ice sheet. Qaqortoq, a town in southern Greenland, set a record daily rainfall of 5.7 inches over the summer. The town of Qaanaaq in northwestern Greenland also experienced flooding. Then, there was the rain on the summit.

“When we see events like we saw in mid-August where we see rainfall at the highest elevations of the ice sheet, I think it portends what we might see in future climates,” says Mote.

Rain negatively affects the health of the ice sheet in several ways. Moon says it can change the shape of the snow grains and make them darker, leading to more sunlight absorption and melting on the surface. The rain can also create ice lenses, which prevent meltwater from percolating into older snow layers in the ground and freezing. Instead, the meltwater would flow off the ice sheet.

Rain would also make life harder for researchers visiting the ice sheet for field research. It would affect everything from the field technology, runways for aircraft, underground food storage and even sewage.

“With every decade warmer than the last, breaking records is the new normal. The ice sheet is in for a wild ride,” writes Willis. “And so are we.”

© The Washington Post