I’ll admit: Having grown addicted to the treats of literary nonfiction, I don’t make it through too many academic histories these days. If I’m going to, there’d better at least be a decent lede—and the Marxian opening to a new history of the eugenics movement in Texas fits the bill.

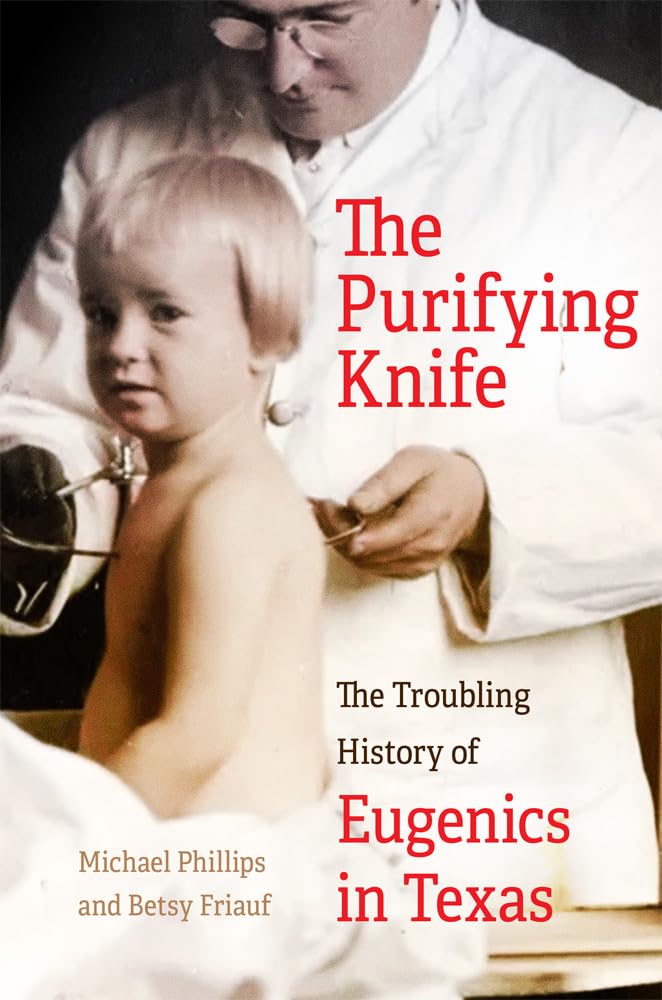

“Monsters haunted the imaginations of some of the most educated white Texans from the 1850s to the dawn of World War II,” tees off The Purifying Knife: The Troubling History of Eugenics in Texas, a 300-page (endnotes included) work by husband-wife historians Michael Phillips and Betsy Friauf.

Philips, who recently retired from a teaching position at the University of North Texas in Denton, previously authored White Metropolis, a well-regarded history of race in Dallas.

The new book, out June 3 from University of Oklahoma Press, unearths a cast of unsavory Texas characters who pushed eugenics—the discredited pseudoscientific belief that the human species should be improved through practices such as forced sterilization—from the mid-19th century through the 1930s. In the latter decades of that period, the majority of U.S. states enacted forced-sterilization laws that targeted the non-white and the disabled, leading to more than 60,000 coerced operations. But Texas, perhaps surprisingly, never passed such a law.

“Although a violent and white supremacist place, Texas remained on the sideline during this particular American carnage,” the authors write. The reasons why are the book’s most interesting subject.

Though the Lone Star State ultimately resisted eugenics, it was home to early pioneers. A Georgia-Texas transplant, Gideon Lincecum was a botanist and surgeon who “one day in the 1850s took it upon himself to castrate an alcohol-dependent patient in Texas, an assault he said cured his involuntary test subject’s addiction.” Lincecum did so before the term eugenics had even been coined, and he became one of the earliest advocates of treating humans more like a breeder treats horses or dogs. Lincecum managed to get the nation’s first forced-sterilization bill put before the Texas Legislature in 1853. But Lincecum, much too far ahead of his time, saw the bill fizzle amid “copious mockery.”

F.E. Daniel, another physician and editor of the Texas Medical Journal from the 1880s until the 1910s, pushed for forced vasectomy and hysterectomy to assure Anglo-Saxon dominance, the book’s authors report. Daniel “embodied the values of the southern Progressive movement,” a particular turn-of-the-century brew that mixed scientific rationalism with rank racism. Eugenicists also made inroads at Texas universities, particularly UT-Austin and Rice.

But Progressives and egghead professors were poor messengers in a state where politicians like “Pa” and “Ma” Ferguson stoked right-wing populist prejudice against government and academic elites—and where religious fundamentalism was a rising political power. Eugenicist proposals, whether focused on sterilization or restricting who could marry, continued to fail.

“Attacks on colleges and universities, therefore, provided the unintentional benefit of shielding the poor and politically powerless in Texas from a horrifying, widely shared elite agenda that prevailed elsewhere,” the authors write. In fact, liberal California was the nation’s eugenic epicenter, where deference to academic expertise helped fuel the largest number of forced sterilizations among states—a practice continued through 1980.

Further frustrating the Texas eugenicists, a large portion of the state’s capitalists depended on cheap Mexican labor and weren’t going to forsake their bottom lines over abstract concerns about race-mixing. John Box, an East Texas Congressman, attempted to overcome these employers when federal lawmakers passed the deeply racist Immigration Act of 1924, which sought to halt immigration from Asia and Eastern and Southern Europe. Box pushed for a cap on Mexican immigration, too, but the Western Hemisphere was ultimately exempted.

“To the wealthy landowners exploiting migrant labor, the threat of paying higher wages proved far more frightening than any dysgenic nightmare that Box and his allies could conjure,” the authors write.

Ultimately, the combination of greedy capitalists, right-wing anti-intellectualism, and solidifying religious opposition (Catholics grew rapidly in Texas during these decades, and the Vatican explicitly opposed forced sterilization in 1930) doomed eugenicist legislation that was considered in Austin between the 1850s and the 1930s. In an email to the Observer, Philips called this “a unique alignment that led one set of bad ideas … to defeat another malign worldview.” Soon, the eugenics movement began its fall from grace nationwide as the discovery of Hitler’s concentration camps generally tarnished proposals for racial engineering.

The history laid out in this book could tempt one to reassess today’s right-wing populist attacks on academia. Perhaps these, too, could end up being right for the wrong reasons. But Philips doesn’t think so.

He attributes universities’ erstwhile embrace of eugenics to higher education’s status as “almost universally white, straight, American-born, male, and wealthy.” More diverse scholarly bodies would have likely eschewed such ideas; a Jewish anthropologist, Franz Boas, eventually did help puncture the movement’s pseudoscience, for example. “That’s why the attacks [today] on diversity, equity, and inclusion today are so dangerous,” Philips wrote the Observer. “It threatens to make universities more like they were at the time eugenics became widely accepted wisdom.”

The book takes a pass through more recent figures trying to revive race science in America, like Charles Murray and Richard Spencer, and the authors also highlight the eugenics-adjacent rhetoric of today’s rabidly xenophobic politicians—namely the U.S. president and the governor of Texas. A bit more provocatively, they tie threads between eugenics and the current fight over abortion. While some on the right make hay of the historic ties between eugenics and early advocates for reproductive rights, the authors take another tack by focusing on the power allowed or disallowed to the state.

“The battle over the right of the state to control reproduction once centered on preventing children labeled as dysgenic from being born. By 2023, the state decided it could force women to give birth even when the child had no chance of survival,” they write. “The two great battles in Texas over government power and bodily integrity since the 1850s, eugenics and abortion, had very different outcomes.”