The record on immigration of the past five years has not just damaged the Conservatives’ reputation but also voters’ confidence in what politicians can do. As a result, voters are more angry and frustrated and often less well-informed than ever.

In the coalition agreement, the Lib Dems accepted the Tory red lines on immigration in return for a deal, not entirely honoured, to end the detention of children. David Cameron’s “no ifs, no buts” pledge to reduce net migration to “the tens of thousands”, which was never compatible with membership of the EU and the obligation to respect free movement of workers, fared even less well. In 2010, the figure for net migration, 252,000, set a new record, but the latest figure stands at another new high of almost 300,000. That is despite a three-pronged attack on students, workers and extended families.

Attempts to limit the number of overseas students in further education and post-graduate workers merely offended valuable partners like India. Immigration from outside the EU remained static: there is a limit on skilled workers, and a higher skill level for employer-sponsored visas. Britons wanting to bring in non-EU spouses now need an annual income of over £18,600, which excludes more than 40% of British citizens. But from the EU, immigration has more than doubled in the past five years, to over 170,000.

The coalition cut the migration impacts fund. Communities were left with little extra support as pressure grew on public services, in particular primary schools, housing and doctors’ surgeries. Headlines about schools where every child spoke English as a second language fuelled rising anxiety about immigration, which became a dominant concern for voters. Yet these fears were often based on inaccurate ideas about the scale of immigration and the number of non-British-born citizens, which politicians failed to challenge by pointing out, for example, that an EU worker who comes to the UK for more than a year is considered to have migrated. It has become received wisdom that large numbers of unskilled migrants from the new EU accession countries are driving down wages and pinching Britons’ jobs, a view often encouraged by the anti-immigration Home Office. In fact, although there are local exceptions, the weight of evidence suggests that migration could account for as much as 0.5% of George Osborne’s tentative recovery.

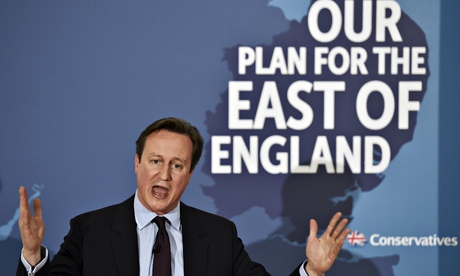

In this tricky context of wide concern and limited powers of action, there is a bidding war from the main parties for 2015. The Conservatives have downgraded their pledge to cut net migration to a mere ambition. In a competitive field, Ukip stands out for its toughness: a points-based system, a five-year freeze on all unskilled immigration, a cap of 50,000 skilled workers a year, and a five-year wait before any migrant can claim benefits. But all the main parties are responding to voters’ concerns that have been inflamed by a lethal mix of political neglect and political over-reaction. So EU citizens would be barred from certain benefits for four years for the Conservatives, and two for Labour. Both Lib Dems and the Tories would end the payment of child benefit to children abroad. Labour rightly emphasises tackling exploitative working practices, but also boosting border controls. Its manifesto also offers a welcome humanity by promising a more generous response to the Syrian refugee crisis and – like the Lib Dems – ending indefinite detention for failed asylum seekers.

How the country imagines itself is always the unspoken context of an election campaign. What sort of a society we want to live in, and what kind of economy will best sustain it – this is the underlying matter of most party policy proposals and most politicians’ rhetoric. Migration speaks directly to both parts of the debate. Britain can be an outward-facing nation, engaged with Europe and the world, capable of building and sustaining a society in which both old and new citizens of the union feel comfortable, and reap the economic rewards that flow from it. But only if politicians frame their arguments in that context. Labour has acknowledged that in government it misjudged both the scale of immigration and how people would react. Now that the Tories have failed to live up their rhetoric of 2010, this is a debate whose parameters need resetting again. No party is ready to take that risk.