The devil might wear Prada, but she definitely does not eat pasta. At least, that seems to be the takeaway from a new interview with Emily Blunt. Speaking to Porter, the British actress who played Emily in The Devil Wears Prada spoke about reprising her role in the highly anticipated sequel, which also stars her brother-in-law, Stanley Tucci. “He’s not good for your Devil Wears Prada diet though, because he’s cooking pasta and making me drink martinis with him every night,” she teased. “He was like, ‘Em, do you want some pomodoro pasta?’ I’m like, ‘I do, but I have to be in Dior couture today, so we’ll see’.”

Blunt might’ve been joking. But her words speak a sadder, more serious truth about the state of an industry’s perennial obsession with thinness, one that has not dissipated at all since the original film came out in 2006. In fact, I think it’s only become more prevalent. Consider the parallels between Blunt’s words and those of her character in the first film, who tells protagonist Andrea Sachs (Anne Hathaway) that she’s trying to slim down for Paris Fashion Week. “I’m on this new diet,” she says. “Well, I don’t eat anything, and when I feel like I’m about to faint, I eat a cube of cheese. I’m just one stomach flu away from my goal weight.”

That quote – funny, absurd, and firmly established in the pop culture canon for all time – might seem like a throwaway line designed to poke fun at fashion. We can laugh because it’s hyperbole; surely nobody would ever actually do such a diet, or try to make themselves unwell to lose weight. Well, as someone who has covered London Fashion Week for around eight years and has several friends in the industry, I can tell you quite confidently that they would. Because this is how people in this industry speak and behave.

I’ve been to fashion shows that have been delayed because models have fainted backstage. I’ve sat on front rows and overheard editors giddily exchange starvation tactics under the guise of diets, or more recently, wellness culture. And I know first-hand that despite years of body positivity campaigns, relentless virtue signalling, and half-hearted calls for diversity, almost every runway I’ve ever sat alongside has been mostly populated by very thin women. Then there are the parties, which have always been (and still are) aplenty in fashion. Dinners, cocktail evenings, breakfasts, and myriad other occasions where food is served and often left entirely untouched.

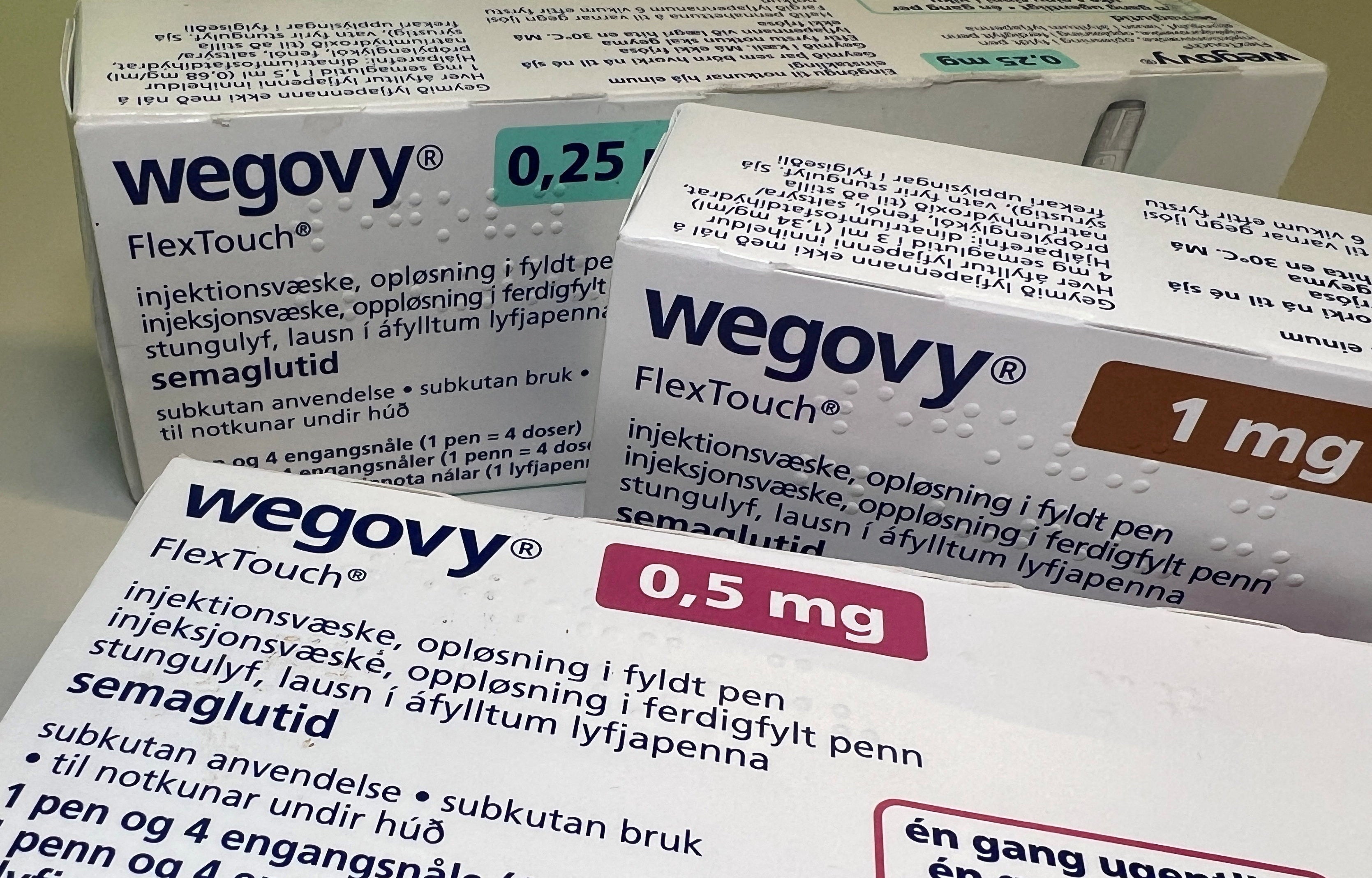

And that was before Ozempic. Since the advent of weight-loss jabs containing semaglutide, such as those also sold under brand names Wegovy and Rybelsus, the fashion world seems to have been on a persistent mission to shrink itself into non-existence. Last year, a friend of mine in the industry rattled off a list of famous models, designers and celebrities who were said to be taking the drugs, which are typically only prescribed to patients with type 2 diabetes, but have been obtained by a litany of people without clinical supervision. All of the women the friend listed were already slim; some, she told me, had suffered from eating disorders in the past.

In the original film, Andy is supposed to be the “normal” woman compared to Emily in terms of her detachment from diet culture; she's just like us! A woman of the people! Someone who is not a sample size! Of course, her trajectory for a second film becomes complicated, perhaps strained, when you consider she's played by a Hollywood actress, one who reinforces society’s increasingly limited beauty standards just as much as anyone else. It doesn’t help, of course, that in recent months, Hathaway has been subjected to countless rumours around what procedures she might and might not have had.

According to data collated by American analytics company Inovalon, off-label usage of semaglutide increased by 256 per cent from 2018-2022. By 2022, the company’s data suggests that more than one in five patients (22.1 per cent) in the US were prescribed this treatment off-label. This is a growing problem for numerous reasons, not least because of how new these drugs still are. Meanwhile, in May, research led by the scientists at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has found that tens of thousands of Americans have ended up in the emergency room after taking semaglutide, with the most common reason being gastrointestinal complications. Symptoms included nausea, vomiting, stomach pain and diarrhoea.

The impact on fashion has been undeniable. Countless plus-size models who were once inundated with work have spoken about their dwindling demand: “The past two years have been really challenging,” said Skye Standley in an interview with The Guardian. “I think there’s been a lot of erasure all around. I’ve noticed a lot less work.” Meanwhile, according to data compiled by Felicity Hayward’s “Include The Curve” report, the number of plus-size women being cast in shows continues to dwindle from season to season. In February, Hayward found that just 22 out of 4,860 models were plus-size on the runway at Paris Fashion Week, marking a 47 per cent reduction from the previous season. Meanwhile, her report claimed that the February shows in New York and London featured 50 per cent and 68 per cent fewer plus-size models, respectively.

All of this is desperately bleak. Not just because it shows how resistant the fashion industry is to embracing a more inclusive definition of beauty, but because of the message it sends to women whose bodies dare to differ from those that we see on the runways. Sure, to those outside of these circles, you might think what fashion designers are doing has no relevance. But to paraphrase Meryl Streep’s character in the first film, the choices those designers make dictate the culture at large, whether it’s the clothes and bodies we’re seeing on a billboard or a red carpet.

It also dictates what we’re seeing on social media, something that didn’t exist when The Devil Wears Prada came out. At least back then, we had a little more respite from all this. Now, images of slim, toned – and possibly Ozempic-built – bodies are ubiquitous, and just a few taps away on our smartphones. A part of me hopes that the sequel addresses all this, highlighting how pernicious it has all become in the fashion industry and beyond. But the cynic in me knows better. After all, if Blunt herself is joking about not eating pasta so that she can fit into her couture for the film, what hope is there for the rest of us?