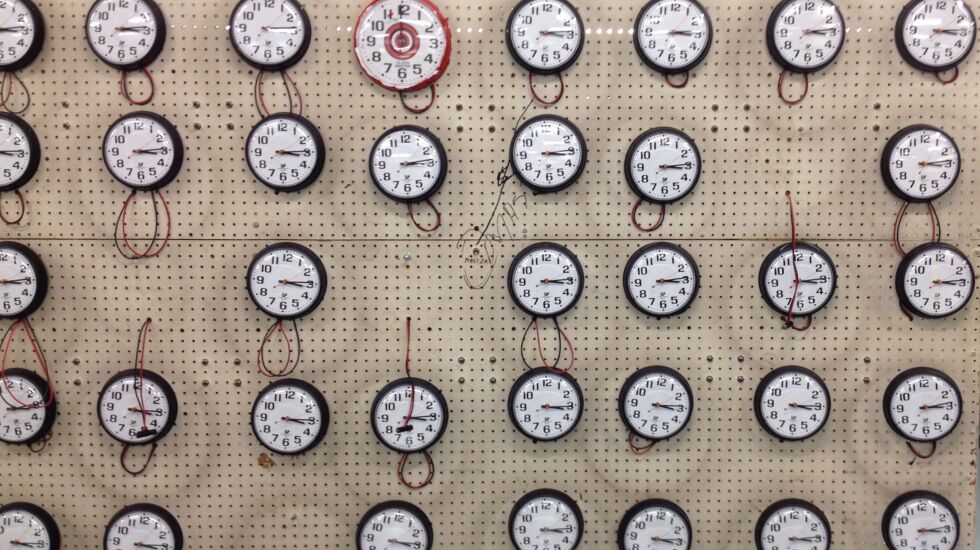

Time stopped in Chicago. On Nov. 18, 1883. Twelve noon arrived and the pendulum of the main clock at the West Side Union Terminal was stilled for nine minutes and 32 seconds, while trainmen stood around, pocket watches in hand, waiting for the future to arrive with a decisive click.

Solar time continued unabated, of course. High noon sped westward during those nine minutes and 32 seconds from the lakefront to Rockford. But solar time, which had guided human endeavor since the dawn of humanity, would never again matter quite so much in Chicago. The second noon of the day, coordinated with Central Standard Time, arrived with a telegraph signal from the Allegheny Observatory at the University of Pittsburgh.

Why is this worth knowing today? Well, besides being a cool story unfamiliar to most, as we grapple with advances in technology, it helps to remember just how difficult even the most mundane changes were when they were new. Not everyone accepted Central Standard Time. Not even all the railroads. The Illinois Central, worried the change would confuse suburban commuters, held out for a week.

And because today, speaking of time — if you are reading this on Wednesday, Oct. 12, 2022 — is also the day my new book, “Every Goddamn Day: A Highly Selective, Definitely Opinionated, and Alternatingly Humorous and Heartbreaking Historical Tour of Chicago” is being published by the University of Chicago Press. I figure, if I don’t notice the event, who will?

The book divides Chicago history into 366 daily vignettes. Some famous, like the Great Chicago Fire or the Leopold & Loeb murder. Some obscure, like the Day With Two Noons, or the surprising number of technological firsts originating in Chicago: not just the cell phone, which many already know about, but a host of developments from videotape to jockey shorts to controlled man-made nuclear fission, from pinball machines to blood banks to malted milkshakes.

I wrote “Every Goddamn Day” during the first year of COVID — time on my hands — and grew to really appreciate the way the one-story-a-day form limited and expanded the material. Aug. 15 is the day both the Picasso sculpture was unveiled in 1967, and the Battle of Fort Dearborn fought in 1812. The first story couldn’t be shifted, so I began telling the second on Aug. 14, with a Potawatomi returning his friendship medal to the fort commander. What for too long was cast as a senseless slaughter becomes a tragic tale of miscommunication and betrayal.

Sometimes I set out merely looking to fill a date and blundered into something fantastic. The Art Institute had three Cezanne paintings stolen in 1978 and didn’t even know they were gone. It’s silly to be proud of Chicago for pizza and hot dogs while being unaware that we also pioneered both public school for students with disabilities and juvenile court.

Odd resonances presented themselves: Maybelline the mascara and “Maybellene” the song were both created in Chicago, and yes, Chuck Berry named the latter for the former, changing a letter in the process.

The book benefited the column and visa versa. I knew that Prokofiev had composed “The Love of Three Oranges” for the Chicago opera, and since the centennial happened to be upon us, wrote a column about it in the paper.

That column prompted a reader to tell me about another first: the first Ibsen play performed in the United States debuted in Chicago. I did not know that.

Nobody in Europe would touch Ibsen’s “Ghosts” — not surprisingly, given its themes of congenital syphilis, adultery, incest, and assisted suicide. None of which stopped Helga Bluhme Jensen and the “skilled dilatants” of the Norwegian-Danish Society from mounting a production at Milwaukee and West Huron in 1882.

Don’t get an author started about his book. We do tend to go on. When I turned it in, I told my editor I so enjoyed writing the book, he didn’t even have to publish it, as far as I was concerned. I had my fun, and sometimes it seems that publication is the punishment inflicted upon authors to compensate for the joy of being allowed to write a book. But publish it they did. You can order it on Amazon, buy it in what bookstores still exist, and if you want to hear more about “Every Goddamn Day,” I’ll be talking about it and reading some vignettes on John Williams show Thursday on WGN-AM (720).