The latest novel from Fiona Neill, best known for her Slummy Mummy columns, is The Good Girl (Michael Joseph, £7.99), a stark morality tale about the perils of sexting. When a video showing 17-year-old student Romy giving her boyfriend a blow job goes viral, the ramifications are grimly easy to imagine. But Neill leaves the aftermath till the end, beginning instead with the months leading up to the incident – a period of domestic strife for Romy’s family, culminating in a move to the country that was supposed to restore order, and might well have done had their new neighbours not been sex therapists Wolf and Loveday.

The Good Girl is vivid and insightful, and Neill has a trained eye for the pressures and poignancies of modern family life. But even allowing for the fact that she has clever parents, Romy is impossibly intellectually sophisticated for her age. And her parents’ professions (father a neuroscientist writing a book about impulse and the teenage brain, mother the head of the secondary school Romy and her siblings attend) have clearly been chosen for their symbolic value. Of course, you could say the same about the characters in Howards End. But no one in Howards End spouts dialogue like this: “Don’t you realise that the release of cortisol under stress means that the amygdala imprints memories that have a strong emotional charge?”

Less ambitious but more effective is Tasha Kavanagh’s pitch-black comedy thriller Things We Have in Common (Canongate, £12.99), also set partly in a school and with bullying as a theme. Here the victim is compulsive eater Yasmin, a half-Turkish girl who falls in love with the blond and aloof Alice, one of the “cool” girls in her class. Yasmin, whose life at home is miserable following the death of her father and her mother’s remarriage, becomes obsessed with the idea that Alice is about to be abducted by a man she sees walking his dog. Stronger than her urge to protect Alice, however, is her greedy awareness that she and the man, who is possibly a paedophile, want the same thing.

This is a novel you read half covering your eyes, willing it not to venture where you fear it might. But of course it does, with great panache. Kavanagh gets Yasmin’s sulky-needy voice just right, so that her warped hunger for power and attention is shown in an ultimately sympathetic context.

MJ Carter’s The Infidel Stain (Fig Tree, £14.99) brings back Jeremiah Blake and William Avery, the stars of her India-set debut The Strangler Vine. Relocating the action to fog-and-cobblestones Victorian London, as Carter does here, is a dangerous move. In The Strangler Vine, Blake and Avery’s fussy Holmes-and-Watson relationship was an incidental pleasure. This new setting brings the Sherlock connection to the foreground and risks diminishing it as we become overfamiliar with the dynamic of their relationship. Still, this is another tremendous performance by Carter: its hallmarks are deep but unobtrusive research, prose that channels Conan Doyle with nimble precision, and a sense that she is genuinely engaging with history rather than using it as set-dressing. We encounter Chartism, suffrage reform and poverty, as Blake and Avery are commissioned by a philanthropic peer to investigate the murders of two dubious printers.

The first novel in Louise Welsh’s dystopian Plague Trilogy, A Lovely Way to Burn, imagined Britain in the grip of a killer flu pandemic known colloquially as “the sweats”. Part two, Death Is a Welcome Guest (John Murray, £14.99), shows us the same events from the perspective of up-and-coming Scottish standup Magnus McCall. Imprisoned on a false charge, McCall emerges from Pentonville to find the world collapsing; though it turns out he and his cellmate Jeb have stronger immune systems than most. Almost everything about this scenario is familiar, from the abandoned luxury hotels to the looped news bulletins on TV. (The internet has, well, broken – a neat satirical touch.) But Welsh’s writing is so effective that it was as if I were encountering these tropes for the first time; as if I was 12 again and watching Threads, the 1980s BBC nuclear drama to which this series is clearly indebted. Richly imagined and, in Welsh’s hands, horribly plausible.

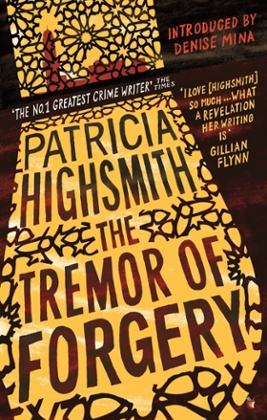

Finally, and pleasingly, Virago has added four more Patricia Highsmith novels to its Modern Classics list: Edith’s Diary, The Blunderer, Deep Water (Gillian Flynn’s favourite Highsmith novel) and The Tremor of Forgery, about an American screenwriter stranded in Tunisia, which Graham Greene considered her finest work. Most people discover the Queen of Misanthropy via the Ripley novels, as they should, but as novelist Denise Mina points out in her introduction, “if you really want to wonder at Highsmith you have to read off-road”.

.png?w=600)