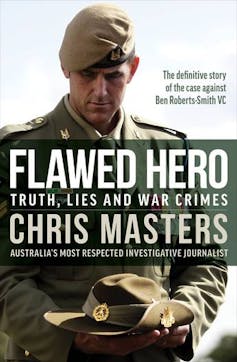

The Australian War Memorial is in the news for reportedly retrospectively changing the rules of its Les Carlyon prize for military history. This resulted in it not being awarded to Walkley award-winning journalist Chris Masters’ book about disgraced special forces soldier Ben Roberts-Smith.

Flawed Hero: Truth, Lies and War Crimes details the evidence Roberts-Smith committed war crimes in Afghanistan. It describes the defamation proceedings brought by Roberts-Smith against Masters, fellow journalist Nick McKenzie and Nine Media.

Masters’ book had been chosen from a shortlist of six by an external judging panel. (The shortlist was first compiled by an internal panel of memorial employees.) Leaked correspondence from the Australian War Memorial suggests the governing council revived eligibility criteria from a few years earlier (when the prize was explicitly for emerging writers only), after Masters’ book had been chosen as the winner.

This disqualified Masters, an author of multiple books. This was the third time the biennial prize, established in 2020, was to be awarded. Instead, it has been deferred.

Eligibility was reportedly broadened in 2022 to include established authors at the request of Carlyon’s widow Denise, one of the prize’s two external judges. This year, she said, Masters’ book had “stood out as the winner”.

The Federal Court found, on the balance of probabilities, Roberts-Smith did commit war crimes in Afghanistan. A fortnight ago, the High Court refused Roberts-Smith’s application to appeal.

The War Memorial has strongly promoted the achievements of the Victoria Cross winner, who featured prominently in its Afghanistan exhibition. The memorial’s former director Brendan Nelson became a strident defender of Roberts-Smith against war crimes allegations.

The head of the memorial’s internal judging panel (and its military history section) warned the Memorial’s director of the consequences of meddling with the prize. Not awarding it in 2024 “may avoid possible short-term uncomfortableness due to the nature of the nominated work”, he wrote in an email, but it would ultimately attract “greater reputational damage”.

“It’s a divided institution, clearly,” said Masters of the controversy. “I know the historians are honourable and I know that they think as I do, that war brings out the worst in us as well as the best in us.” He believes the judges saw awarding his book as “as an opportunity to discuss something […] discomforting but important”.

What is the purpose of national history?

This latest controversy follows criticism of governance processes concerning the half-billion-dollar expansion of the War Memorial, aired by the ABC’s Four Corners program earlier this year.

It raises important questions about the very purpose of the Australian War Memorial and the values it espouses.

Should the memorial avoid aspects of Australian military experience that cast our service personnel in an unsavoury light? Does it exist to describe Australian war experience truthfully, or to celebrate an idealised version of it? Is it a shrine to Australian military achievement and a vehicle for a certain — somewhat traditional, aggrandising and masculinist — version of nationalist pride?

Or is it a site for the appreciation of courage and sacrifice, but also for examination and reflection?

These are important questions, loaded with a significance that extends well beyond the walls of the War Memorial itself. The ways nations represent themselves in their cultural institutions have significant implications for the values that lie at their core.

It is no coincidence the Trump administration’s “anti-woke campaign” is targeting organisations such as the Smithsonian Institution and the Kennedy Center in its effort to remake the cultural landscape of the United States.

Making warriors sacred and venerating military prowess has proved particularly potent as a means of generating nationalist feeling. Students of history can point to many examples where the combination of chest-beating nationalism, aggressive militarism and blatant manipulation of the historical record has led to dire outcomes.

They include the conduct of European empires in the lead-up to the first world war, and of Japan and Germany during the 1930s, in the lead-up to the second world war.

The actions of the War Memorial also raise vital questions about information and truthfulness. As events in the US underline, the effective functioning of a democracy requires a consensus about adhering to basic principles of truth and fact.

The War Memorial Council effectively disqualified a book that demolished the reputation of a man it had venerated as a modern embodiment of the Anzac ideal. How it represents our history is a measure of our national values.

Origins of the Australian War Memorial

The man who conceived the Australian War Memorial, Charles Bean, understood the connection between the representation of war and our national ethos.

The official correspondent of the first world war and later its official historian, Bean was wary of creating an institution that celebrated or romanticised war. Indeed, he resolved to create a “war memorial museum”, as he bore direct witness to the battle of Pozières in July 1916. Australia suffered 23,000 casualties in less than seven weeks of bitter fighting.

Bean envisaged an institution that was a monument to those who served, as well as a museum containing “relics” of the war. (He preferred the term, with its sacred connotations, to the more bellicose “trophies”.) He also imagined the institution would hold a vast archive of letters, diaries, unit histories and other documents that would illuminate the experience of those who served.

Bean was adamant the Memorial’s galleries and exhibitions would not glorify war, denigrate the enemy, or boast of victory. They must avoid doing these things, Bean believed, for “both moral and national reasons and because those who have fought in wars are generally strongest in their desire to prevent war”.

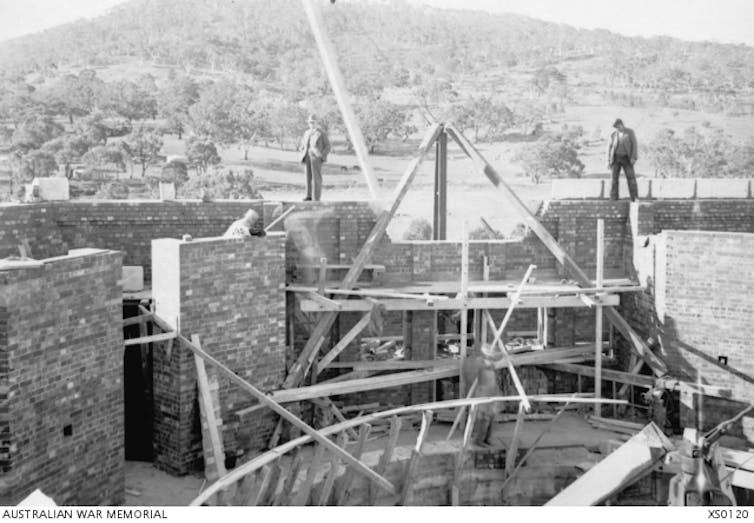

The foundation stone of the magnificent art deco building at the foot of Canberra’s Mount Ainslie was laid in 1929. The Great Depression delayed completion of the Australian War Memorial, which did not open until 1941, in the midst of another global conflict. The remit of the memorial was naturally expanded to include the second world war. In 1952, during the Korean War, that brief was again expanded. The War Memorial would now represent all Australian wars and operational service.

The institution’s current role, outlined in the Australian War Memorial Act (1980), requires it to function as a national memorial of Australians who have died “on or as a result of active service, or as a result of any war and warlike operations in which Australians have been on active service”.

The act also requires the memorial to maintain a collection of historical and exhibit material, to facilitate research into Australian military history, and to disseminate information about our military history.

Frontier conflict

Conflicts after the second world war, such as those in Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan – as well as peacekeeping activities – have been added to the memorial’s responsibilities without controversy.

But when historian Geoffrey Blainey suggested in a 1979 report the War Memorial should consider representing frontier conflict, his proposal was ignored. In those conflicts, more than 10,000 Indigenous people (perhaps many, many more – between 20,000 and 60,000) were killed by European Australians.

The issue became the subject of public controversy in 2008 when the memorial’s then director, Steve Gower, arguing against including the frontier wars, referenced a report he had commissioned from his Military History section. It concluded Australian military forces were not involved in “the wars”.

Recently departed principal historian Peter Stanley publicly responded he’d had “nothing to do with the report”, and was not consulted despite “having researched the frontier wars”. Stanley has continued to be a prominent advocate for representing frontier conflict at the memorial, most recently as president of the Defending Country advocacy group.

Those in favour of coverage of the frontier wars have seized on the opportunity presented by the current A$550 million expansion of the memorial. Council chair Kim Beazley appears to favour increased representation of the wars.

Resistance remains, however, among members who include military officers, former prime minister Tony Abbott, and former national RSL president and Australian Defence Force reserve officer Greg Melick.

Melick has said publicly that the memorial’s exhibitions should be limited to those representing defence personnel and peacekeepers who served in wars and conflicts overseas.

To date, the director has committed only to a small expansion of frontier war coverage in an area to be named the “Pre-1914 Galleries”. One of the less remarked on aspects of the controversy about the Carlyon prize is a leaked email in which memorial director Matt Anderson observes “considerable work on difficult content has informed what will go in the new (and existing) galleries”.

Will the memorial decide to fulsomely represent an “uncomfortable” part of Australian history – one that jars with stories of heroism and derring-do? The answer will be revealed when the redevelopment project is completed in 2028.

What kind of country?

While the issue of frontier conflict has been diverted by critics into a debate about how we define the memorial’s charge to represent “war and warlike operations”, the current controversy cannot be so easily sidetracked from the real issue at stake.

Roberts-Smith was on active operations overseas. He has been found, on the balance of probabilities, to have committed or been complicit in the murders of four unarmed Afghan men.

A less defensive, more enlarging approach on the part of the Australian War Memorial Council would acknowledge that our military history includes both acts of sacrifice and courage, and acts we collectively condemn because they contravene our basic values.

A capacious approach would include unfamiliar perspectives, and suffering that differs from our own. These issues are not confined to the eligibility requirements for a book prize. They are about ensuring we don’t glorify war – and that we prize truthfulness, as far as we can determine it.

They go to the heart of our values as a nation.

Carolyn Holbrook receives funding from the Australian Research Council. She is affiliated with Defending Country.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.