In the late ’90s, not long after I left Cameroon to attend college in the United States, I learned of a word used in certain African-immigrant communities to refer to African Americans: Akata. It was not uttered with affection; far from it—Akata means “wild animal,” and thus has much in common with the N-word. In my early days here, it wasn’t unusual for me to see a fellow African look at an African American and say, with a sneer, “Look at that Akata,” or “I just don’t understand these Akatas.”

Days after George Floyd was killed, I attended a Zoom memorial of sorts, organized by Africans for Africans, so we could mourn his death together and think of how we, as a community, could better treat our American brethren. The ludicrousness of this was not lost on me—that it would take so long, take a tragedy of this public magnitude, for us to see what America had been doing to our brothers and sisters; that it would take a graphic video for both immigrants and citizens of America to comprehend what they’d wrought in fostering an environment in which African Americans are so often treated like animals.

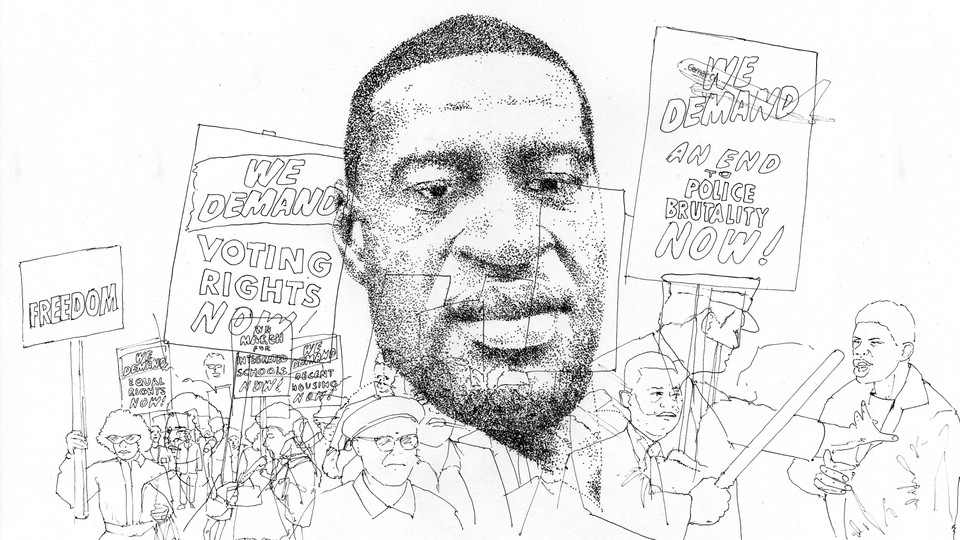

Early on in His Name Is George Floyd, Robert Samuels and Toluse Olorunnipa make mention of the fact that George Floyd wanted to change the world. “As long as anyone can remember,” they write, he “wanted the world to know his name.” It is hard to read this sentence and not feel a twinge of sadness, considering that the world did not come to know his name in the way he’d imagined. It’s unlikely that Floyd ever dreamed he would one day cause an entire nation—nay, the entire planet—to reckon with its centuries-long destruction of Black bodies.

As Samuels and Olorunnipa tell it, Floyd’s aspirations were quite ordinary—he wanted, among other things, to be an athlete and achieve fame and fortune, but American racism stood in his way, and Floyd stood in his own way, largely as a reaction to American racism standing in his way. This mélange created an unsustainable situation that was all but bound to explode.

[Read: Why Minneapolis was the breaking point]

Samuels and Olorunnipa deserve every praise for presenting Floyd as the complex character that he was—what human isn’t? Both writers are Black men and could easily have diluted portions of the book that show Floyd’s many shortcomings and poor decision making, but they resisted the urge. The result is an expertly researched and excellent biography, a necessary and enlightening read for all, especially those who, like my fellow African immigrants in the ’90s, have ever looked upon young Black men in the inner city with disdain.

If America were a more perfect union, George Floyd might have been born into a wealthy family thanks to his industrious great-great-grandfather, a former enslaved person who “after more than thirty years of working as a free man … had managed to amass five hundred acres of his own farmland” in a period when, at one point, “less than 2 percent of White farmers in North Carolina held more than five hundred acres of land.”

But America then, and now, is not a place where white people are overly comfortable with Black success, so white men had Floyd’s ancestor dealt with, eventually dispossessing him of all those acres and ensuring that later generations would not get a sniff at the American dream. And so it would be. By the time George Floyd was born in October 1973, every generation since his ancestral land was stolen had known only failed dreams. He spent his early days living with his family in a trailer park in North Carolina as his parents nursed the pains of their futile attempts to escape poverty. Their marriage ended when Floyd was still a boy, and his mother moved, along with her children, to Houston, where they ultimately settled in a housing project “with a population that was 99 percent Black and most residents living well below the poverty line.”

Still, his was a fairly happy childhood, surrounded by a loving mother, siblings, relatives who regaled him with stories of his ancestors, and a community where everyone felt as if they were part of one big Black family. Such sections of the book, which depict how much Floyd was loved and how much he loved back, are a joy to read, a celebration of one of the many beauties of African American culture—a people’s ability to get together and eat and laugh and have an overall good time, as if they weren’t one of the most persecuted people in human history.

In addition to his community, Floyd was blessed with a teacher—a white teacher, as it happens—who “put together a curriculum designed to engender a sense of Black pride and potential” in Floyd and her other students. It was in part thanks to her that Floyd was a solid student in elementary school and proceeded to become a star athlete in high school. His high-school football team’s attempt to win the state championship is a thriller in its own right, but its achievement did little to help Floyd become a pro. When his athletic ambition failed, his descent began.

[Read: The enormous scale of this movement]

This much is clear: George Floyd was a devoted son, a loyal friend, a caring sibling, an esteemed member of his community. He was also a drug user and trader, not the hardest worker, someone convicted of aggravated robbery—you’d have to read the story of the robbery to decide for yourself whether he was truly guilty—and far from a great boyfriend, though he never seemed to run out of women eager to fall in love with him and go to great lengths to make him a better man. Did he want to become a better man? Yes, he did, and he made several attempts at it. After cycling in and out of prison, falling in and out of drug addiction, he picked up and, with the help of a friend determined to see Black men turn their lives around, moved to Minneapolis in search of redemption and a chance to atone for his mistakes. He yearned to create a life he would be proud of, especially because, by then, he had a child, a daughter named Gianna, whom he dearly loved.

Anyone who was old enough in 2020 knows what became of him in Minneapolis.

But Samuels and Olorunnipa are not interested merely in replaying that horror story. Theirs is a far more ambitious mission, to demonstrate all the ways in which American laws and government policies (intentionally racist or otherwise) conspired against George Floyd. And there is no shortage of examples.

Richard Nixon declared a War on Drugs in the ’70s, treating drug abuse as a crime rather than as a public-health concern, something that an aide to Nixon later admitted, as Samuels and Olorunnipa paraphrase it, was an effort to “target, vilify, and disrupt Black communities—seen at the time as a political threat to the president.” It worked. Ronald Reagan cut the social safety nets that had benefited poor families like the Floyds, sending them into deeper poverty. The state of Texas in 1990 started requiring all high-school students to pass an assessment test as a requirement for graduation, despite being aware that a majority of its Black students, Floyd included, were unprepared and would fail. And if one is inclined to think that anti-Black measures were largely pushed by conservatives, the Democrats did their fair share of showing that they too could be tough on crime (read: Black people) when Bill Clinton signed a crime bill sponsored by then-Senator Joe Biden.

Is it therefore a surprise that when the sun rose on the day of his death, George Floyd was a poorly educated Black man with a history of drug abuse, multiple health problems, and a list of criminal convictions and stints in prison, flailing through the early days of a pandemic that was disproportionately affecting Black folks? Samuels and Olorunnipa don’t need to answer that question; it is clear from their work that America had been slowly killing George Floyd for decades before Derek Chauvin pressed the last breath out of him.

Which is why it is confounding that the authors shy away from more pointedly calling out the hypocrisy of governments and corporations and all manners of institutions that immediately took the knee, vigorously condemned Chauvin, and pledged their allegiance to anti-racism, not because it was just but because it suited them. The authors know this, and yet a good portion of this book is spent on the Chauvin trial and the theatrics of the aftermath of the killing, as if all the superficial changes in the world will prevent future tragedies of this nature.

Perhaps I am transferring my disappointment with America onto Samuels and Olorunnipa. Perhaps I am unfairly asking them to do more than bear witness. I imagine they would say, in their defense, that putting America on trial for the death of George Floyd is an impossibility, and beyond the scope of this book. Fair enough, but deep down I know, many of us know, that even with Chauvin in prison, justice has not been fully served. Those entities that created the conditions for Floyd’s death carry on. They thrive. Their next victim awaits.

[Read: George Floyd was also a father]

This, perhaps, was why at the end of reading this book, I felt nothing but a deep exasperation. An exasperation not unlike what I experienced after reading Nathan McCall’s Makes Me Wanna Holler, and Jeff Hobbs’s The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace, similarly outstanding books that chronicle the plight of modern-day African American men.

Such accounts are even more imperative these days, because, despite all the Black Lives Matter bumper stickers on our cars and signs stuck into our yards, despite all our self-professed “wokeness,” these authors know that millions of George Floyds still live among us and we as a nation do not care enough whether they live or die.

But what good is cynicism? George Floyd, as presented by Samuels and Olorunnipa, was a man of tremendous hope. Notwithstanding the many millstones this country threw around his neck, he continued to believe that he would overcome. It was always absurd to imagine that Floyd’s killing would somehow lead to the end of systemic racism—certainly Kamala Harris’s assertion, as Samuels and Olorunnipa characterize it, that Floyd’s death “could allow the country to sing a new song when it came to racial justice” seems laughably naive just two years later. But the portrait that remains is of a man who encouraged others to never give up, a man who would have urged us to never stop fighting for a more just America and to never stop believing that there shall surely come a day when stories like his will no longer need to be told.