1984

The inaugural Turner prize – awarded for “the greatest contribution to British art in the previous year” – goes to painter Malcolm Morley, who has been living in America for 20 years (and doesn’t turn up), to the outrage of critics, commentators and the arts minister, Lord Gowrie. Handing out the £10,000 cheque, stumped up by an anonymous donor, Gowrie baldly states his preference for the land art of Richard Long, who will be shortlisted three times before finally winning. The first two winners were Morley and Howard Hodgkin, and there won’t be another painter for 13 years Photograph: Rosie Greenway/Getty Images

1988

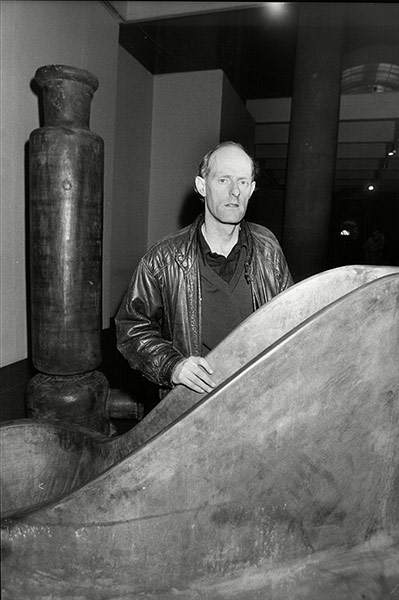

Sculptor Tony Cragg wins out in the stiffest competition ever, against Richard Hamilton, Richard Wilson, Richard Long and Lucian Freud, not that the public knows this, as the publication of the shortlist – supposedly humiliating to established names – is abolished, only to be restored two years later after media protest. Only Cragg’s work is shown at the Tate, so the original aim of the prize – to encourage more people to look at more art, as the Booker prize encourages reading – is comprehensively thwarted. Nicholas Serota becomes Tate director and immediately restricts the prize to artists only (as opposed to curators: Serota himself had been nominated), but still the rules are critically chaotic. This will never change Photograph: Malcolm Clarke/REX

1990

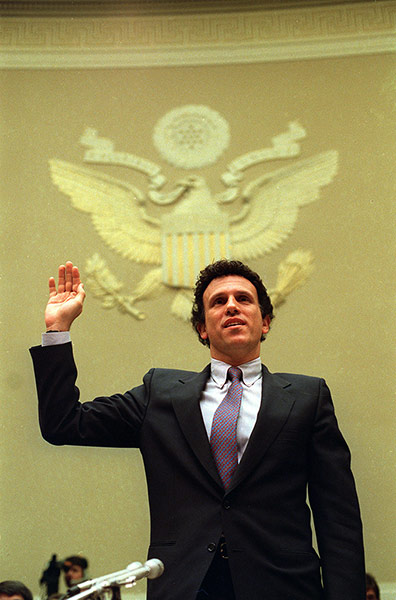

Drexel Burnham Lambert, the investment bank now subsidising the award, goes bust in the junk bond scandal. There is no sponsorship; there is no prize. It has been looking more like a lifetime achievement award of late, in any case, but all this changes when Channel 4 offers to sponsor and televise the prize from 1991. The public is invited to submit nominations, the emphasis is on new stars, and the over-50s are no longer eligible. This is the Turner prize as we now know it – evergreen controversy, the media puffed up like angry bullfrogs over conceptual art, punning headlines and ratcheting William Hill odds Photograph: J. Scott Applewhite/Associated Press

1993

Rachel Whiteread wins both the Turner prize and the anti-Turner prize for the ephemeral and haunting House, her plaster cast (which stands on the same spot) of the interior of the last remaining house in an East End terrace before its demolition. The local council will shortly destroy the sculpture too. The K Foundation’s £40,000 award for “the worst artist in Britain” has an identical shortlist; Whiteread accepts and gives the money to charity. (Despite the unprecedented outrage provoked by his prize-winning pickled cows in 1995, Damien Hirst does not receive a K Foundation award) Photograph: Jon Bradley/REX

1997

Gillian Wearing, the winner, shows 60 Minutes of Silence, in which a group of police officers (or actors, as it later turns out) manage to stand still for an hour in a mesmerising endurance test that splits the critics. Tracey Emin is drunk on the live Channel 4 discussion programme, ripping off her microphone and storming out; she later claims to have no memory of the event (and in a collective mis-memory, is widely thought to have won the 1999 prize herself for the notorious unmade bed). This is the first and, to date, last time the prize has an all-female shortlist (Wearing, Christine Borland, Angela Bulloch and Cornelia Parker) Photograph: Courtesy Maureen Paley, London

1998

Chris Ofili wins, providing this year’s tabloid talking point for the elephant dung balls attached to and propping up his paintings – including one of a black mother of Christ, The Holy Virgin Mary, which will later enter the Tate’s collection. Dung is deposited on the museum steps in protest. The annual hoopla, and the surrounding furore, have now become such a social fixture that celebrities are becoming involved. Neil Tennant of the Pet Shop Boys is the first of the celebrity judges; fashion designer Agnès B awards the prize. This is the boom time, when Ofili can win over such gifted artists as Tacita Dean Photograph: Richard Young/Rex

2002

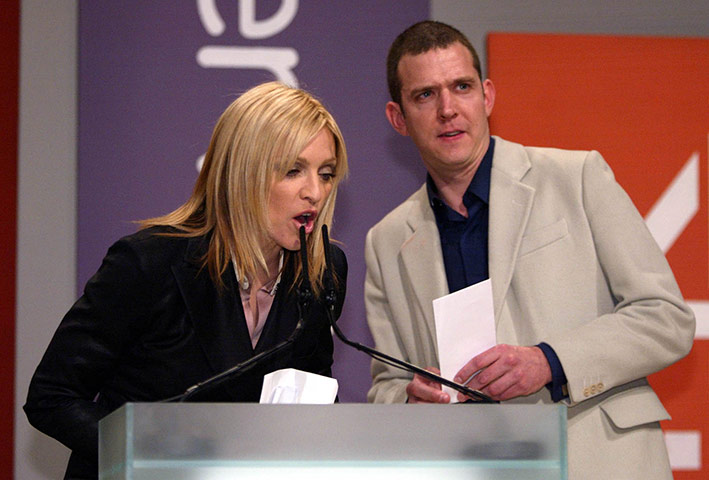

Catnip for the headline writers, Martin Creed’s Work No. 227: The lights going on and off is possibly the most ridiculed of all prize-winning works. No matter that the Tate has by now installed a gallery full of pamphlets and filmed interviews with the artists as context for visitors, and Creed’s characteristically wry and philosophical remarks might have deflated the most indignant opponent. Eggs are thrown at the walls. The choice of Madonna to present the prize is scorned as shameless marketing, especially when she swears on air before the watershed. Channel 4 gets an official warning from the Independent Television Commission Photograph: Dan Chung/Reuters

2006

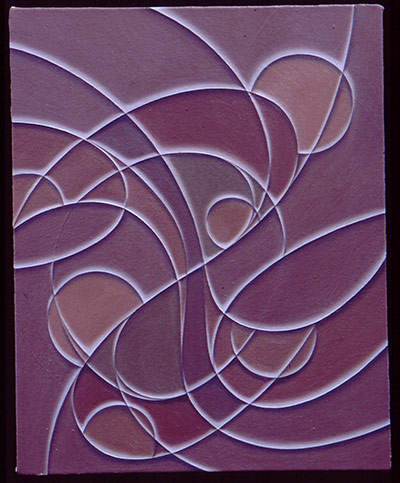

Lynn Barber’s year, as it's known, when the Observer writer breaks with the jury’s traditional vow of silence to reveal what everyone has long suspected: that the judges are frequently working from catalogues and slides. And that some of them have never set eyes on the work of the shortlisted artists until it arrives in the gallery. Tomma Abts wins the £25,000 prize for her delicate and epigrammatic abstracts. Not that the public can see what the jury might (or might not) have admired, for the shortlisted art is never the same as the work displayed in the Tate exhibition accompanying the prize – yet another Turner prize anomaly Photograph: Courtesy of Tomma Abts

2008

The dullest year yet, comparable only to 2002 when the almost classically boring wooden shack – Shedboatshed, by Simon Starling – won the prize. The shortlist is now properly international, like the British art scene itself, with artists from Bangladesh and eastern Europe. But the works include an installation of dirty dishes, a lecture on cinema and some drip-dry photomontage that could scarcely hold anyone’s attention, and which rely heavily for what little meaning they have on the pamphlets and films in the context room. The Turner prize is not quite dead – Mark Wallinger was the much-admired winner the previous year – but is certainly dormant Photograph: Dave M. Benett/Getty Images

2013

The prize relocates to Derry after outings to Liverpool and Gateshead, attracting record visitor numbers, certainly more than in London. This year one of the prize’s serious flaws has at last been resolved: the shows for which the artists were shortlisted are mainly in Britain, so that judges and public had a fair chance of seeing them. Two very popular artists are shortlisted – David Shrigley and Tino Seghal – their work enthusiastically conscious of its viewers. Laure Prouvost wins. In a perfect reversal, some commentators actually miss the rude, crude, eye-poking, brain-jabbing YBA 90s. And the Turner prize never quite stands still: 2014 features the youngest and least-known shortlist in the award’s history Photograph: PR