Which Side Are You On? (1931)

Reece was the wife of a union organiser during a bloody miners’ strike in Harlan County, Kentucky. After harassment by the mine owners, she dashed off this stark, stern call to arms for the resurgent union movement. Like all early protest songs, it borrowed an old melody, in this case the Baptist hymn “Lay the Lily Low”, the better to spread among the crowds. First recorded by Pete Seeger’s band the Almanacs 10 years later, it has since been rewritten for events ranging from the Mississippi Freedom Rides to the 1984-85 miners’ strike

(Click here to hear Reece's version) Photograph: Public Domain

A Change Is Gonna Come (1964)

Stung into action by hearing Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” (“Jeez, a white boy writing a song like that?”), Cooke wrote a song that reflected the concerns he discussed with friends such as Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali. A statement of faith under pressure, it unites the pain of blues and the perseverance of gospel, Cooke’s conviction building with each repetition of the title, while René Hall’s sensitive arrangement provides a grand, cinematic backdrop. Almost half a century later Barack Obama paraphrased the chorus in his 2008 victory speech Photograph: Redferns/Getty

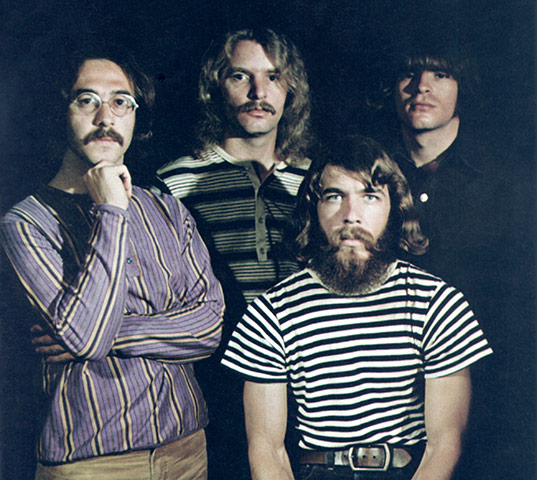

Fortunate Son (1969)

Some songs opposing the war in Vietnam risked being insipid and condescending. John Fogerty’s broadside looked through the eyes of a blue-collar GI. “Screaming inside” at the injustice of well-connected young men escaping the draft, Fogerty scrawled the lyrics in just 20 minutes and sang them like he was calling in an air strike. The initial inspiration was David Eisenhower, grandson of Dwight and son-in-law of Richard Nixon, but it found an even more fitting target in George W Bush during the Iraq war

(Click here to watch a live performance) Photograph: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty

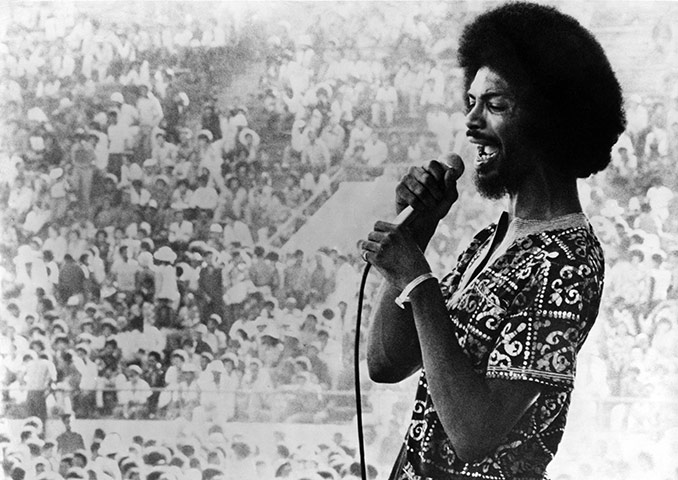

The Revolution Will Not Be Televised (1970)

At 21, Scott-Heron was already a published poet and novelist when he launched his recording career. He charted a path between the hard-nosed street poetry of the Last Poets, the socially conscious soul of Curtis Mayfield and the agile, mordant wit of Bob Dylan. The 1971 revamp, with its muscular bassline and darting flute, became a much-abused inspiration for lyrics, headlines and advertising slogans. Scott-Heron has dozens of great songs but only this one has become part of the language

(Listen here) Photograph: Redferns/Getty

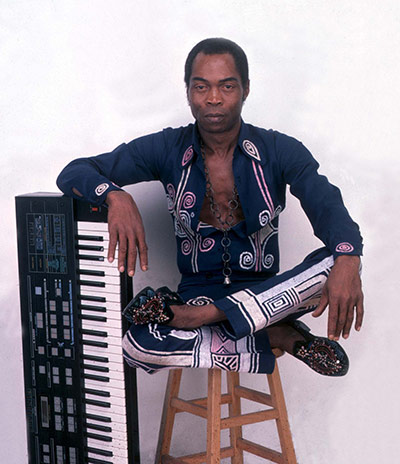

Zombie (1976)

Some protest songs are denied airplay, others are denounced, but it’s blessedly rare that one triggers an armed reprisal. A flamboyant rule-breaker and magnet for dissidents, Fela was already a thorn in the side of the Nigerian authorities when he recorded this infectious and impertinent satire on the army. Its popularity helped bring tensions to a head and soldiers raided Fela’s compound, brutalising everyone inside before burning it to the ground. What you hear in this winding Afrobeat groove, though, is not disaster but joyous, irrepressible defiance Photograph: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty

Police and Thieves (1976)

During this horrendous election year in Jamaica, when armed gangs aligned with the two rival parties left scores of people dead, and almost claimed the scalp of Bob Marley himself, you could hardly move for protest songs . Murvin’s hit typified what you might call crisis reggae: of-the-moment social commentary blended with biblical prophecy and delivered in deceptively sweet tones over a liquid rhythm. After it soundtracked that year’s volatile Notting Hill carnival, the Clash covered it, making explicit British punk’s debt to reggae’s revolutionary fire

(1980 Top of the Pops performance here) Photograph: Redferns/Getty

Ghost Town (1981)

The Specials’ Jerry Dammers claims that he was inspired to write “Ghost Town” as much by terminal tension within the band as by the bleak mood on the streets, but a fluke of timing — it reached No 1 in the same week riots swept Britain — made it aural shorthand for the era of mass unemployment and police harassment. Forget the history for a moment and the song is still an extraordinary achievement: it unfolds like a horror movie, with disparate voices emerging from the fog with dire warnings and barely suppressed violence. The mood is the message

(1981 Top of the Pops performance here) Photograph: Eugene Adebari/Rex Features

Two Tribes (1984)

Nuclear armageddon played out as a loony disco bacchanal, packaged with an arsenal of promotional gimmicks and — here’s the punchline – blasted to No 1 for a phenomenal nine weeks. Wasn’t 1984 strange? Just as relations between the US and USSR were at their pre-Gorbachev worst, “Two Tribes” was almost indecently exciting, with singer Holly Johnson as a mad ringleader, not sure whether to fear annihilation or relish it. Engineered by ZTT Records to be not just a single but a cultural event, it still sounds inspirationally unhinged — an anti-war record like no other

(On Top of the Pops here) Photograph: Ilpo Musto/Rex Features

Fuck tha Police (1988)

Of course, hip-hop produced many cleverer, more persuasive songs than this – “The Message” and “Fight the Power” to name just two. What “Fuck tha Police” had on its side was sheer, breathtaking belligerence which connects like a fist. Thrillingly immoderate, it drew predictable flak from police associations and the FBI, but also from liberal hip-hop fans who preferred their protest without the lurid gangland posturing. It was Exhibit A in the nascent debate about violent rap lyrics, but when the Rodney King trial and the LA riots rolled around, it rang loud and true Photograph: Rex Features

If You Tolerate This Your Children Will Be Next (1998)

A pro-war song? Technically, yes, in that Nicky Wire’s lyric pays tribute to the International Brigades who fought against Franco in the Spanish civil war. But its real subject is the modern-day narrator, a pacifist who wonders what, if push came to shove, he might be prepared to fight for. A self-searching protest song on a par with the Clash’s “(White Man) In Hammersmith Palais”, it was taken to No 1 by its yearning, elegiac melody

(Live on Jools Holland here) Photograph: Jon Super/Redferns