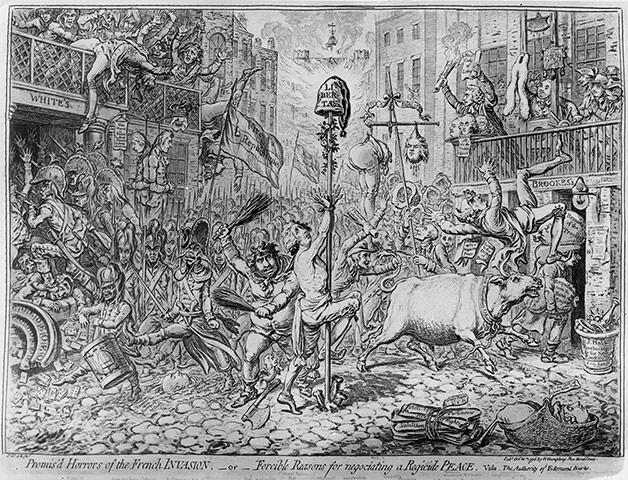

Ice and fire

Charles Fox was short, fat, smelly, a liberal, an internationalist, a drinker, a gambler, a womaniser and a flamboyant orator; even opponents regarded him as a lovable rogue. William Pitt was tall, thin, shy, fastidious, a conservative, an imperialist, a speaker who destroyed opponents with fluent logic; probably died a virgin. According to Shelley, “Mr Pitt is stiff with everyone but the ladies.” Their epic confrontations, amidst the tumult of the French Revolution and its aftermath, established the contours of modern parliamentary politics Photograph: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The duellists

We often talk about political competition being deadly. Viscount Castlereagh and George Canning are the only two rivals who actually tried to shoot each other. In 1809, these two Tories fought a duel on Putney Heath over who was to blame for a setback in the war against Napoleon: Castlereagh hit Canning in the thigh. Even the jaundiced world of the early 19th century was astounded when it learnt that two senior cabinet ministers had tried to kill each other. Both men resigned and the government fell Photograph: Bridgeman Art Library

Dizzy versus the Grand Old Man

Queen Victoria adored the dandyish Benjamin Disraeli, who coaxed her out of mourning and made her Empress of India. She abhorred the priggish William Gladstone, complaining that he addressed her “as if I were a public meeting”. The cynical, witty, opportunistic, romantic Jewish Tory versus the austere, moralistic, self-righteous, self-flagellating Anglican Liberal is the definitive clash between the politician as showman and the politician as preacher Photograph: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Squiffy and the Wizard

The precise and phlegmatic English prime minister forged a tremendously successful partnership with his charismatic Welsh chancellor. Together they drove forward the great, reforming Liberal government of the early years of the 20th century. This relationship was transformed into internecine rivalry because of the stress of fighting the first world war. Asquith, outstanding in peacetime, proved unequal to the challenge of being a war leader. In 1916, he was overthrown by Lloyd George Photograph: MacGregor/Getty Images

Reversal of fortunes

In the autumn of 1938, Neville Chamberlain waved from the balcony of Buckingham Palace to the huge crowd cheering him for bringing back “peace in our time” from his Munich negotiation with Hitler. Winston Churchill, denounced by Chamberlain and his cronies as a warmonger and alarmist, looked washed up. But, by the spring of 1940, Chamberlain had been toppled and a vindicated Churchill was prime minister, rallying his nation as no one else could for the titanic struggle with the Nazis Photograph: Science Museum Photo Studio/SSPL via Getty Images

Unfraternal feelings

The most poisonous rivalries are often within the same party. When Barbara Castle tried to improve Britain’s chronically bad industrial relations in the late 1960s, her fellow Labour cabinet minister Jim Callaghan ruthlessly worked with the trades unions to torpedo her plans. On becoming PM in 1976, he fired her, saying that he wanted “someone younger in the cabinet”. To which she retorted: “Then why not start with yourself, Jim?” Three years later, Callaghan’s premiership was destroyed when his old union chums unleashed the Winter of Discontent Photograph: Getty Images

Blond ambition

Both headstrong and exhibitionist blonds. Both capable of arousing wild passions in followers and opponents. It was always likely that these two large egos would not be able to co-exist in the Tory cabinet of the 1980s. Heseltine pioneered council house sales, an early success of Thatcherism. As defence secretary, he fought CND as ferociously as his leader. But an always uneasy relationship snapped over the Westland affair. He stormed out of the cabinet and, four years later, launched a leadership challenge that triggered her downfall Photograph: Rex Features

The two Davids

At the time he tried to laugh it off, but David Steel has since admitted that he was wounded by the Spitting Image representation of the leaders of the SDP/Liberal Alliance. The Steel puppet was a squeaky figure living in the pocket of a giant David Owen. When the 1987 election did not produce a breakthrough, Steel acted quickly to show who was master by advocating a merger of the parties. Owen tried to carry on with a separate SDP that was eventually killed by national ridicule, beaten at a byelection by the Monster Raving Loonies Photograph: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The TB-GBs

When the two mighty figures of New Labour were working together, they were pretty much unstoppable. When they were battling with each other, which became increasingly the case the longer their volatile partnership went on, government was riven and paralysed. There was fault on both sides, but at the heart of this rivalry was Brown’s inability to come to terms with the fact that the younger man had beaten him to the crown and his impatience to replace Blair as prime minister before their time in power was up Photograph: Murdo Macleod

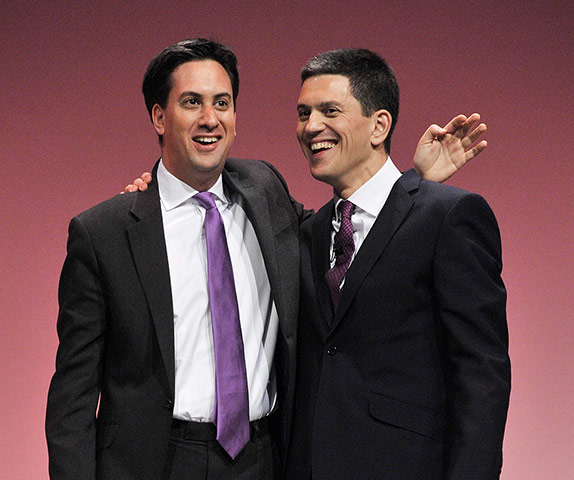

Et tu, brother?

Our five most recent PMs all had an older brother, or, in the case of Thatcher, an older sister. Perhaps the competitive edge is honed by being a younger sibling. It was overlooked by David Miliband, who was late to spot that the greatest menace to his ambitions to lead Labour lurked within his own family. David had beaten his kid brother into parliament and was the first into cabinet. But, when it came to the top spot, in this version of the biblical story, Abel slew Cain. Ed seems to have got over shattering David’s dreams. The same can probably not be said of David Photograph: Rex Features

.jpg?w=600)