Court of King James, 1604

The Tragedy of Othello, the Moor of Venice was first performed by the King’s Men at the court of James I in November 1604. The show starred Richard Burbage, Shakespeare’s greatest contemporary interpreter. No one knows if Burbage blacked up for the part: issues of racism did not surface until the 20th century. The themes of lust, jealousy and betrayal were an instant hit with audiences. Iago, derived from the medieval figure of misrule, became one of Shakespeare’s classic villains not least because he has the play’s largest part, approximately one third of all the lines Photograph: Bettmann/Corbis

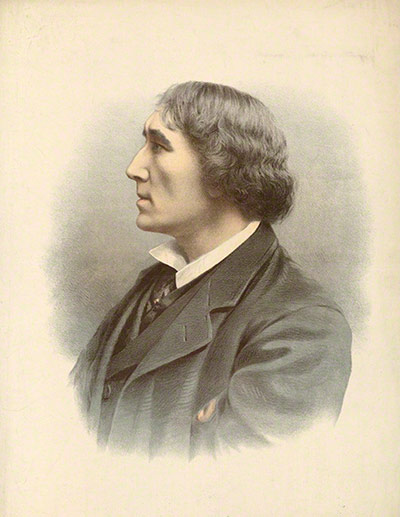

Covent Garden, 1833

Shakespeare knew the meaning of showbusiness. Othello always generated such onstage electricity it was never adapted or revised during the 17th and 18th centuries. It reverberated among actors and audiences as one of the great theatrical experiences: savage, visceral, transgressive. All big-name actors wanted the role. One of the biggest to cause a sensation in the part was Edmund Kean, often playing opposite Sarah Siddons. His last stage performance was Othello at Covent Garden where, collapsing on stage in 1833, he expired soon after, with the words, 'Dying is easy; comedy is hard' Photograph: PR

Haymarket, 1837

By the 19th century, Shakespeare’s reputation was beginning to acquire its present status. Ambitious producers would experiment with new casting ideas to keep the canon fresh. In 1837, the West End actor Samuel Phelps alternated Othello and Iago with his celebrated contemporary William Macready. This innovative role swap, from night to night, was repeated by Henry Irving and Edwin Booth in 1880. Again, in 1955, Richard Burton and John Neville exchanged leads during an Old Vic season. Today, the trend against white actors playing the Moor has put this wheeze out of favour Photograph: Charles and Mary Lamb, Tales from Shakespeare

Lyceum, 1876

Othello’s appeal to actors is that he’s a wonderfully romantic protagonist who has some terrific lines – Shakespeare at the top of his game. This is hardly surprising. As a composition, the play comes soon after Hamlet and just before Macbeth (and King Lear). There was a new patron (James of Scotland) to please, and a new audience to entertain. Othello was intended to be a crowd-pleaser. Over the centuries it has attracted all the top performers. Few were as celebrated or admired as the Victorian actor-manager Henry Irving, who played the role in 1876 Photograph: National Portrait Gallery London

Savoy, 1930

Paul Robeson, son of a former slave, was an iconic American star. His performance in 1930 brought Othello into the modern age. At last a black man played the Moor, and was, by all accounts, utterly mesmerising. Only an audio version of this performance survives, but it hints at an extraordinary theatrical moment. The spectacle of a black man kissing a white woman – Desdemona, played by Peggy Ashcroft – was a sensation. On first night, Ashcroft won rave reviews, and Robeson received 20 curtain calls. The production ran for more than a year Photograph: Angus McBean/RSC

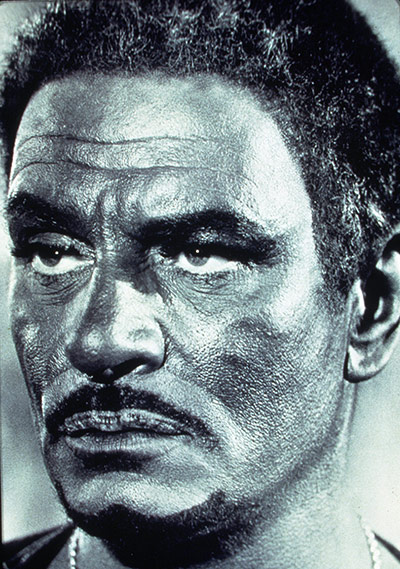

National theatre, 1964

In 1964 Olivier played Othello as if Robeson’s performance had never happened. Declaring this was 'the impossible one', he immersed himself in technicalities of makeup and costume, and told Life magazine that 'the whole thing will be in the lips and the colour'. Edith Evans disapproved; it is one of Olivier’s most disputed roles. Still, on one memorable night his fellow actors applauded backstage. Olivier slammed the dressing-room door. 'I know,' he said, 'but I don’t know how I did it, so how can I repeat it?' Franco Zeffirelli gushed that the performance summed up 300 years of acting Photograph: Rex Features

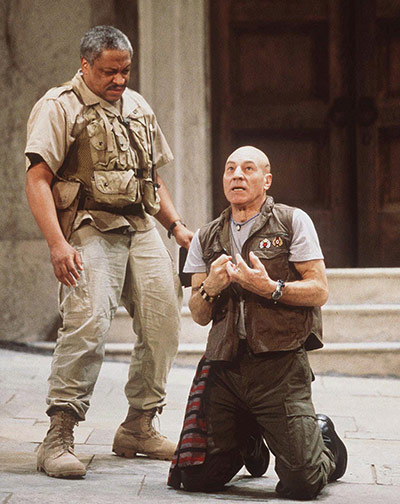

Washington DC, 1997

Stewart turned the part into a reinterpretation of the whole play. His was the first white Othello for half a century. Subsequently, he did a so-called “photo negative” production: the other cast members were black, while his Othello appeared with a shaved head, earrings and a serpent tattoo. Once again, the juxtaposition of Othello’s tragic emotional blindness with Iago’s visceral and obsessive hatred worked its magic. Coleridge described Iago’s onstage torment as 'the motive-hunting of motiveless malignity'. Stewart’s performance found a strange humanity in Othello’s vulnerability to Iago’s relentless torture Photograph: Carol Rosegg/AP

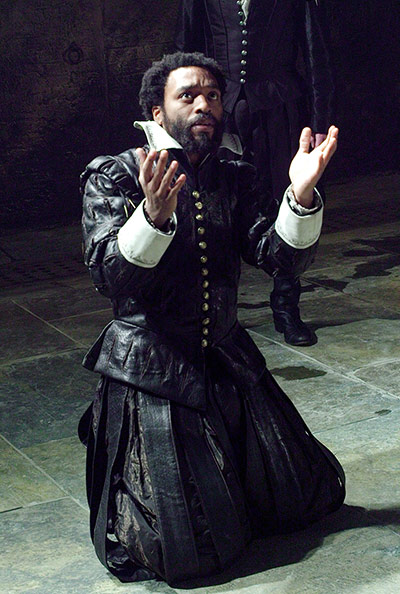

Donmar, 2007

Michael Grandage’s outstanding 2007 production at the Donmar Warehouse starred the Nigerian-born Chiwetel Ejiofor as the Moor, opposite Ewan McGregor’s Iago. Desdemona, performed by Kelly Reilly, was exceptional, but McGregor was not at ease in his part. Ejiofor was a sensation among audiences and critics alike, and the show became one of the season’s hot tickets. The Observer’s Susannah Clapp called him 'the best Othello for generations', and Ejiofor went on to win an Olivier award for best actor. He has not appeared in a Shakespeare play since Photograph: Robbie Jack/Corbis

Trafalgar Studios, 2009

Lenny Henry followed Ejiofor in 2009, making the transition to serious theatrical work. It was an uneven production, directed by Barrie Rutter. The star’s TV fans packed the house but the tragedy remained elusive. At least this version eschewed the iconoclasm of Frantic Assembly, an experimental theatre group which translated the scene to contemporary northern England. Here the Moor, played by Jimmy Akingbola, became the one black inhabitant of a derelict working-class town. Othello, no longer a great soldier, has worked as the doorman at a local pub, and much of the action took place around a pool table Photograph: Tristram Kenton

Berlin, 2009

Possibly the most radical Othello was at Berlin’s Deutsches Theater in 2009, with Othello played white, by a German actress, Susanne Wolff. Upending Shakespeare’s interplay of race and gender meant Desdemona would be in love with a woman. This 'reinterpretation' involved the Moor in weird costume changes. At first Wolff appeared in white shirt and black trousers, but when Othello learns of Desdemona’s alleged infidelity, she reappeared in a gorilla suit, apparently as 'a metaphor for the Moor’s animal rage'. Eventually, Othello morphed into a blonde in a red dress Photograph: Arno Declair/deutschestheater.de