1 | Aneurin Bevan

Brighton, 1957

Some momentous political issues just keep on coming around, as do the passions they arouse. During its 13 years in the wilderness between 1951 and 1964, Labour was often at war with itself, many of the fiercest clashes fought over the nuclear deterrent. Nye Bevan, the party’s greatest orator of the period and founding minister of the NHS, was a hero of the left, but shocked and dismayed them when he opposed unilateral disarmament. Accusing its advocates of “an emotional spasm”, he minted a striking metaphor when he appealed to delegates not to send a future Labour foreign secretary “naked into the conference chamber”.

2 | Hugh Gaitskell

Scarborough, 1960

One test of the worth of a conference speech is whether it has poetry or power that still echoes down the decades. Gaitskell was leader during one of Labour’s least fruitful periods and never became prime minister. But he could put words together. Defeated by the conference – the bomb was the issue once again – he brushed off the humiliation and roused his supporters by vowing to “fight, and fight and fight again to save the party we love”. The decision to commit to unilateral disarmament was reversed a year later. In the wake of Jeremy Corbyn’s election as leader, some are commending Gaitskell’s rallying cry to Labour’s aghast moderates.

3 | Harold Wilson

Scarborough, 1963

Labour leaders have been most successful at bidding for power when they have managed to locate their arguments in a compelling story of national renewal. It was near the peroration of his speech about the pace of technological change that Wilson told his audience that the country would only prosper by forging a “new Britain” from “the white heat of this revolution”. It painted the Tories as old-fashioned and, as he later wrote, was also designed to “replace the cloth cap with the white laboratory coat” as the popular image of Labour. Conference rhetoric is often not matched by reality and so it proved in this case. In government, Wilson struggled to achieve his aspirations to improve investment and industrial relations.

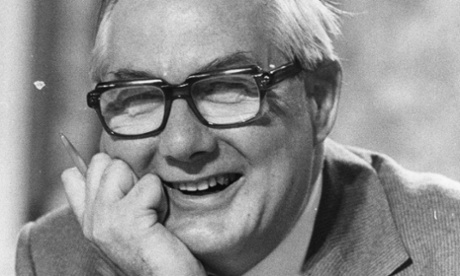

4 | Denis Healey

Blackpool, 1976

That year’s Labour conference was an occasion of high drama and even higher stakes. It met in the midst of a severe economic crisis exemplified by a plummeting pound. Chancellor Healey broke off from bailout negotiations with the International Monetary Fund to dash north to Blackpool where his challenge was to persuade an angry party that it had to accept a package of spending cuts as the price of the deal with the IMF. This bulldozer of a speech, delivered through a barrage of booing and heckling by dissenters, was described by the Guardian’s political editor, Ian Aitken, as “a brutal, belligerent performance”. It did the trick. At the climax, the protesters were drowned out by an ovation from loyalists.

5 | Jim Callaghan

Brighton, 1978

OK, so I’ve slightly bent the rules because this speech was made to the TUC conference. It merits inclusion for being the only time a party leader has sung a song in a major speech and for its historical significance. After a torrid period for his government, an apparent break in the weather encouraged speculation that Callaghan was about to call an autumn election. He mocked those pressing for him to go to the polls by offering a rather tuneless rendition of Waiting at the Church, a music-hall song about a jilted bride. The decision to delay proved disastrous. It was followed by the winter of discontent, defeat by Mrs Thatcher.

6 | Neil Kinnock

Bournemouth, 1985

Kinnock was always a high octane orator and never more so than when he denounced the Trotskyite entryists of the Militant tendency with special reference to the way in which they had run Liverpool council. “You start with far-fetched resolutions. They are then pickled into a rigid dogma… irrelevant to the real needs, and you end in the grotesque chaos of a Labour council – a Labour council – hiring taxis to scuttle round a city handing out redundancy notices to its own workers.” Derek Hatton shouted “liar”. Eric Heffer stomped out. The conference gave Kinnock a tumultuous ovation for answering the yearning for a full-frontal assault on the hard left. It was a critical milestone in the party’s long march back to power.

7 | John Prescott

Brighton, 1993

After four election defeats at the hands of the Tories, Labour was now in the care of John Smith. He staked his leadership on a proposal to replace the union block vote with voting by individual union members. The conference was finely balanced and defeat might have forced his resignation. An unshowy performer himself, Smith looked to Prescott to use his trade union credentials to win over the waverers, which the former seaman did with an extraordinary speech. The grammar was a complete car crash, but the meaning was crystal and passionate. “This man, our leader, put his head on the block,” he said of Smith. The vote was won. Prescott’s career soared towards the deputy leadership.

8 | Tony Blair

Blackpool, 1994

Elected as leader that July, Blair saved the bombshell in his debut conference speech to the very end when he declared an intention to rewrite Clause IV of the party’s constitution, with its historic commitment to mass nationalisation, and introduce a new statement of aims and values that would dedicate the party “to the many not the few”. Advance copies of the speech given to journalists did not include the last page to keep the surprise total. It was of symbolic rather than practical significance: the Labour party had long since given up on wholesale public ownership of industries. But that symbolism was highly potent. After leftwing dissent was overcome, “the Clause IV moment” was a major building block in the creation of New Labour.

9 | Tony Blair

Brighton, 2001

Some Blair fans will prefer his 2006 swansong after he had been forced to announce his retirement in which he joked about Cherie: “At least I don’t have to worry about her running off with the bloke next door.” Blair haters will object to the inclusion of any of his speeches. This one, delivered as the world reeled in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, was the most passionate, eloquent and definitive statement of his worldview. It won a rapturous standing ovation from the audience and rave reviews from newspapers of all political complexions. One half-awed, half-alarmed member of the cabinet described it to me as: “The inaugural speech of the president of the world.” He over-promised when he told his audience that they could “reorder this world” by banishing conflict, poverty and disease. What actually followed was the war in Iraq.

10 | Gordon Brown

Manchester, 2008

Beset by the worst financial meltdown since the 1930s, dreadful poll ratings and a plot among Labour MPs to oust him from No 10, Brown turned the crisis into an opportunity to save his besieged premiership. He stressed that serious times needed someone with serious experience at the helm:in other words, himself. “I’m all in favour of apprenticeships. But this is no time for a novice.” It was a clever barb directed at those after his job. His spinners had pre-alerted the broadcasters. So when he delivered the line, the TV shots cut away to David Miliband, the foreign secretary and chief pretender, who was forced to grit his teeth and join the laughter.