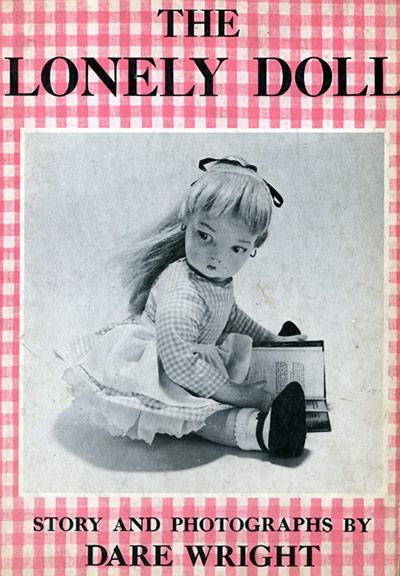

Dare Wright (1957)

This beautiful book by the New York photographer was a bestseller when I was a child. The black-and-white photographs have glamour, mystery and melancholy. Edith, a doll, is expectantly dressed: she has a glossy ponytail, a lace petticoat and adorable black shoes. But she is on her own, praying for company. The pigeons she feeds give her no crumbs of comfort. Then two bears stroll into her life… The book has recently been republished, which is amazing, if only because Mr Bear, I am sorry to report, believes in smacking his charges Photograph: PR

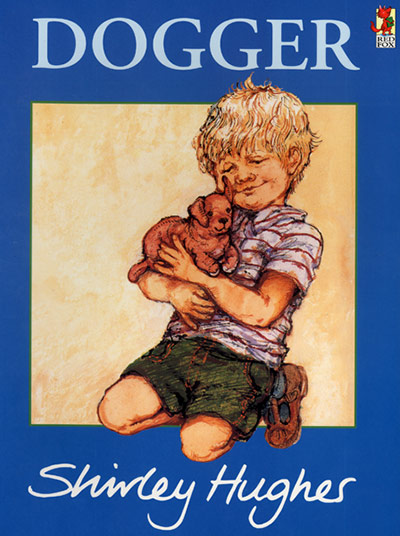

Shirley Hughes (1977)

This is Hughes’s most heartwarming picture book, a comfort read about what happens when Dave loses his toy dog. It avoids sentimentality and evolves into a story in which a sister is outstandingly generous to her little brother. Hughes has a kindly, inexhaustible eye – she misses nothing. Look at that big, vulgar teddy that will save the day – one recognises his sort instantly. Her drawing is invariably superb and usually describes a reassuring world for children – sometimes happier-than-thou. She has illustrated more than 200 titles – she is a virtuoso Photograph: PR

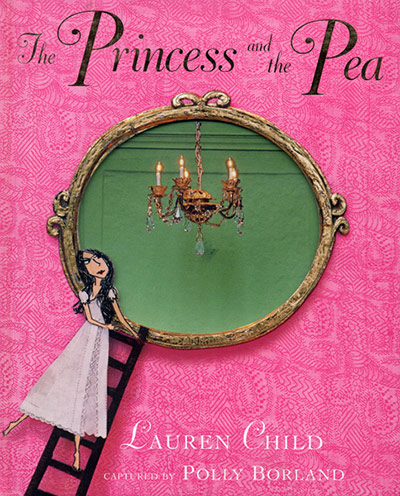

Lauren Child, captured by Polly Borland (2005)

This collaboration between photographer Polly Borland and illustrator Lauren Child was a labour of love – and it shows. Child has created miniature settings out of cornflake packets with fastidious care and furnished them with tiny, handmade antiques and diminutive chandeliers. It is a book that has a doll’s house appeal. And, even if she is not to your taste, Child’s princess with her oval face and slanting eyes is arresting. A millefeuille of mattresses forms the frontispiece – with a pea teasingly visible. A romantic hybrid and a dashing retelling of an old tale Photograph: PR

Quentin Blake (1990)

The joy of this book is that it celebrates family life at its most rousingly impossible. It works beautifully read aloud – with all joining in. Blake’s gift as an illustrator is his agility: he conveys an enormous amount in the flow of the line and the breeziest of his sketches are complete portraits. His adults are eccentrics, his children anarchists. Look at Amy, puce in the face, in a riot of discarded socks. You can almost hear Eric’s deafening cry and register that it won’t be easy to get – let alone bring – Bernard up Photograph: PR

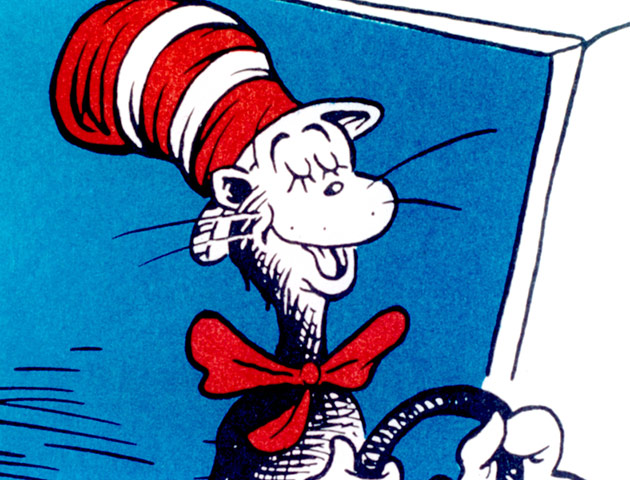

Dr Seuss (1957)

Dr Seuss is the most successful American picture book illustrator of all time. His motto “fun is good” is worth remembering. But the cat in the hat is a complicated character. He enters with his eyes peculiarly closed. His hat bends as if it were alive. There is something sinister beneath the bonhomie – and the RSPCA should be on to him for the way he treats that fish. And as to Thing One and Thing Two, they may help with the housework but they are a creepy duo. The power of the book is that it exists on the edge of children’s panic. Extraordinary to discover it was originally written as a school reader, a “controlled vocabulary book” Photograph: Everett Collection/Rex Features

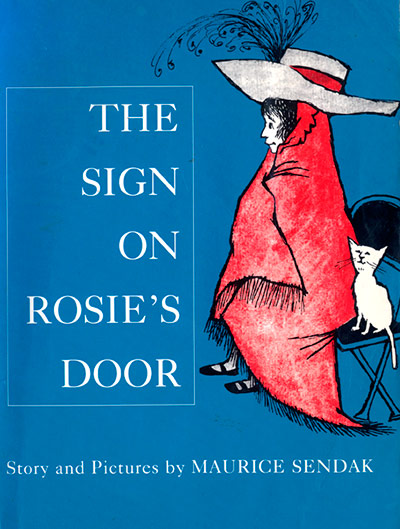

Maurice Sendak (1960)

Sendak is another illustrator who has created a world – but his celebrated Where the Wild Things Are does not eclipse The Sign on Rosie’s Door, an early work of exceptional charm. Like most of Sendak’s books, it explores the way a child moves between fantasy and reality. Rosie instructs friends to address her as “Alinda, the lovely lady singer” but soon discovers the rigours of a performer’s life. Even Rosie’s back view – hopeful and dressed up to the nines, the dress slipping slightly off one shoulder – tells all Photograph: PR

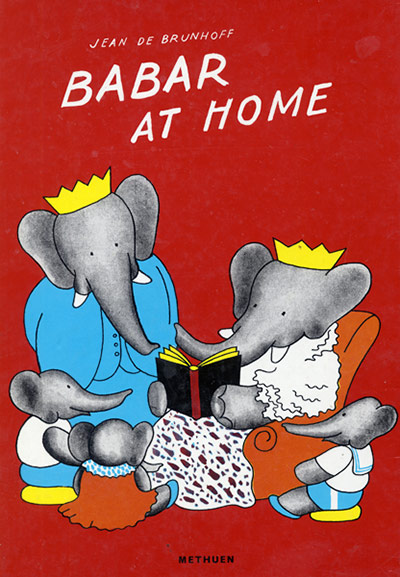

Jean de Brunhoff (1938)

Babar helped launch picture books as a genre. His green suit is the most chic in literature (de Brunhoff was French and knew about clothes). But Babar is also a model father (no slapping from him). He is tenderly hands-on – or trunk-on – with his triplets – Pom, Flora and Alexander – and plays games with them in the nursery. He is the most human of elephants, concluding to his wife after a trying day which included saving Pom from a hungry crocodile: “Truly, it is not easy to bring up children… but aren’t they worth it!” Photograph: PR

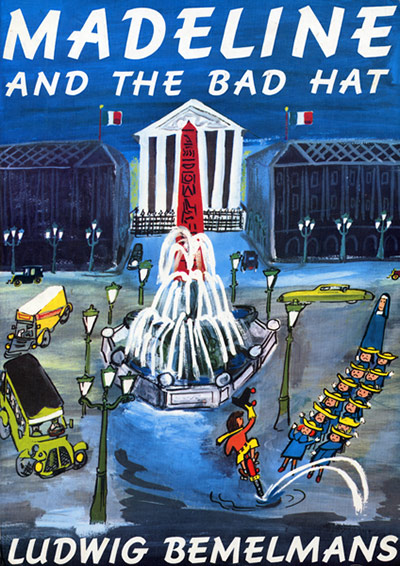

Ludwig Bemelmans (1956)

Another bad hat in the repertoire is Pepito – dysfunctional son of a Spanish ambassador and tormentor of animals. He sticks all the neighbourhood’s cats in a sack and then releases them to the dogs. The story fascinated me as a child because it was so alien – its virtue and vice equally unnerving. It stars 12 convent girls. Madeline, the smallest and pluckiest, tames Pepito. The nun, conveyed with daring simplicity, resembles the black top of a pen. Bemelmans (1898-1962) was an Austrian-born painter. His drawings, against a yellow background, have an angular, unforgettable panache Photograph: PR

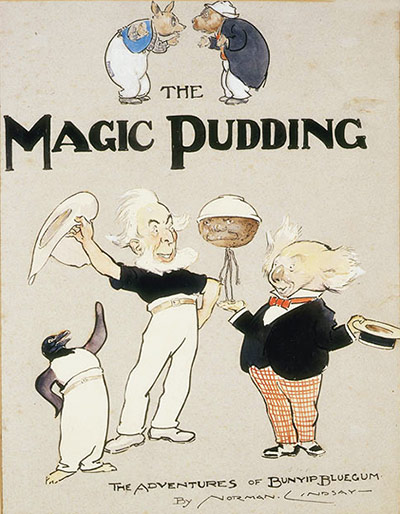

Norman Lindsay (1918)

In this Australian classic, Bunyip Bluegum, a dapper koala, promenades around Australia and meets two rough diamonds: Bill Barnacle, a sailor, and Sam Sawnoff, a penguin. They tuck into a magic pudding named Albert – one of the most outlandish creations in children’s literature. The pud has spindly legs, a nasty disposition and a tendency to run away. Norman Lindsay (1879-1969), a painter, created here a world of irresistible antipodean lowlife. We chase two pudding thieves – possum and wombat – through this triumphant tale divided into four hefty “slices” Photograph: PR

Shaun Tan (2000)

At the end of this book, the narrator says: “I still think about that lost thing from time to time.” And so will Tan’s readers. The lost thing is strange: tomato red with grey tentacles. It is inert, friendly and nameless. Tan’s haunting story is about what it means to be lost and found – dropped off in a place of unclaimed objects. The Lost Thing is surreal and metaphysical. It makes you look – and think – twice. A modern Australian triumph – but much more forlorn than The Magic Pudding Photograph: PR