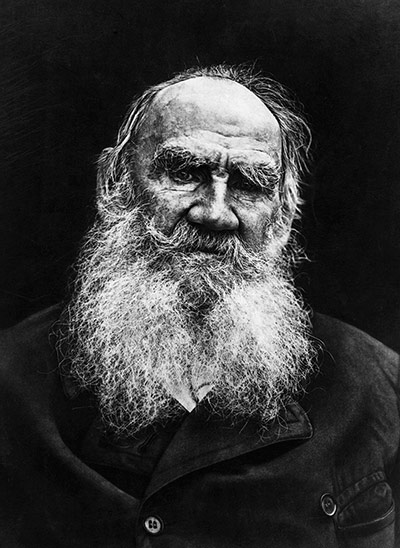

Tolstoy’s 1869 novel - often described as the greatest ever - chronicles the effects of the Napoleonic wars on five aristocratic Russian families. Deploying the technique of literary realism that he helped develop, Tolstoy magnificently evokes the sense of an entire social world. The narrative moves seamlessly between characters and scenes, now describing the inanities of a Moscow drawing room, now charting, in harrowing detail, the chaos of war. Tolstoy’s aim was to use the techniques of fiction to get at the “truth” of history Photograph: Hulton/Getty Images

The 2009 Booker winner is the first in a series of novels (the second, Bring Up the Bodies, has just been published) presenting the life of Tudor statesman Thomas Cromwell. With remarkable immediacy, Mantel inhabits the restless, brilliant, ambitious mind of her subject, so that we see the events of Tudor history - notably Henry VIII’s divorce from Catherine of Aragon - unfold through his eyes. Mantel’s Cromwell emerges as a force for progress at a time when, arguably, a recognisably modern British identity was established Photograph: Murdo Macleod

The great Victorian novelist’s foray into historical fiction is a sprawling epic about Renaissance Florence, which centres on Tito Melema, an Italianate-Greek scholar who becomes a conniving politician, and his wife Romola. The novel takes in many key figures of the time, including the Dominican friar Savonarola and Machiavelli. Critics have stressed the resemblances between Eliot’s Florence and Victorian Britain (also a society in a state of flux) as well as parallels between Romola and her creator: both women of formidable learning who led unconventional lives [This caption was amended on 15 May 2012 to correct the spelling of Savonarola] Photograph: The Print Collector/Corbis

Set in Sicily during the Risorgimento of the 1860s, Lampedusa’s only novel, posthumously published in 1958, is a rich portrait of an aristocratic order in decline, based on the life of his great grandfather. Lampedusa brings a modernist sensibility to 19th-century history as he charts the meandering, opulent life of Prince Fabrizio - the “leopard” of the title. The descriptions of houses and landscape are mesmerising, and were well captured in Visconti’s sumptuous 1963 film, starring Burt Lancaster in the role of the Prince. [This caption was amended on 15 May 2012 to correct the spelling of Lampedusa]

Photograph: Getty Images

The Walter Scott prize defines a historical novel as having to be set at least 60 years prior to its publication; under this, Colm Tóibín’s early 1950s-set novel, published in 2009, would just be ruled out. Still, Brooklyn is a stunningly controlled account of an important historical phenomenon: Irish immigration to America. Eilis Lacey leaves her home in Enniscorthy for a new life in Brooklyn, and there experiences both desperate isolation and quiet excitement. By confining himself scrupulously to Eilis’s point of view, Tóibín succeeds in making her experiences seem fresh and real Photograph: Murdo Macleod

The 2011 Costa-winner charts the progress in pre-revolutionary Paris of the young engineer Jean-Baptiste Baratte, who is given the thankless task of overseeing the destruction of the church of Les Innocents and the clearance of its cemetery. As well as telling a gripping story, the novel dramatises some major conflicts of the Enlightenment: between history and progress, remembering and forgetting. Miller superbly evokes the smells, sounds and sights of 18th-century Paris in lean prose that plunges you into the era without appearing to have to work too hard to get every period detail right. Photograph: Sarah Lee

Fitzgerald’s final novel - published in 1995, five years before her death - dramatises the life of 18th-century German aristocrat Friederich von Hardenberg, otherwise known as the Romantic poet Novalis. It centres on his love, in his early 20s, for Sophie von Kühn, who is only 12 when he falls for her. (They become engaged but she dies of tuberculosis two years later.) Like all Fitzgerald’s novels, The Blue Flower is slim, and is full of shifting perspectives and brief impressionistic scenes. It’s regarded by many as her finest work, but didn’t make the 1995 Booker shortlist - a decision some see as inexplicable Photograph: Jane Bown

This hugely popular 1934 novel is the fictional autobiography of the fourth Roman Emperor. Graves uses this format to present the history of Claudius’s predecessors - Augustus, Tiberius and Caligula - while his 1935 follow-up, Claudius the God, is an account of his subject’s own rule. Claudius’s various disabilities - including a stammer - led to him being shielded from public life during early adulthood, but Graves presents him not as a harmless idiot but as a courageous figure. Graves later dismissed the books as having been written solely for commercial gain, but they remain classics of the genre Photograph: Bill Brandt/Getty Images

Martin’s 2003 novel is a devastatingly honest, sometimes brutal portrait of life on a slave plantation in the 1830s. The narrator is Manon, a young woman trapped in a loveless marriage to her boorish, plantation-owner husband. Manon rebels against her matrimonial subjugation, and acts with bravery in her efforts to improve her lot. In some ways, she’s a feminist pioneer. Yet she’s incapable of applying the same logic to the greater injustice of slavery, whose propriety she never questions. Martin’s novel, shot through with irony, remains somewhat underrated, despite winning the Orange prize Photograph: Murdo Macleod

Barker’s early 90s trilogy is the story of psychiatrist William Rivers and his pioneering treatment of various First World War soldiers - including Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen - for shell shock at the Craiglockhart war hospital near Edinburgh. Barker blends fact and make-believe to create an absorbing drama that takes in many themes besides war, including mental illness, class, homosexuality and creativity. The books were deservedly acclaimed on publication and the third, The Ghost Road, won the 1995 Booker prize. Barker was led to the subject by her husband, a neurologist familiar with Rivers [This caption was amended on 15 May 2012 to correct the title of The Ghost Road, not The Road Home as we had it]

Photograph: Murdo Macleod