Cimitero Acattolico, Rome

Sometimes referred to as the “English” or “Protestant” Cemetery in Rome, this meadow in the shadow of an ancient pyramid is best known to visitors as Keats’s Graveyard for it was here, in February 1821, that the Romantic poet was laid to rest. He had hoped Italy’s milder climate might ease his tuberculosis, but it precipitated his death at just 25, before his poetry was widely recognised. His dismay at his failure to make a mark led him to insist that his name should not appear on his tombstone. He wanted only “Here lies One Whose Name was writ in Water”. His friends added an explanation about “the Bitterness of his Heart at the Malicious Power of his Enemies” but that seems superfluous now that his genius is recognised Photograph: Kathy deWitt /Alamy

Père-Lachaise, Paris

Wilde’s grave vies with that of Jim Morrison as the biggest tourist attraction in this graveyard of the great and good (Balzac, Chopin, Delacroix, Ingres, Molière, Piaf, and the lovers Abélard and Héloïse among others). It is regularly covered in red lipstick kisses and is both a lovers’ rendezvous and a rallying point against homophobia. The memorial – a naked birdman made by the sculptor, Jacob Epstein – has proved controversial. Unveiled in 1914, it had to be covered up because of complaints about the figure’s exposed genitals. A fig leaf was added but in the 1920s a group of anti-censorship protestors tried to chisel it off and ended up inadvertently carrying out a castration. The detached lump of stone was said to have ended up as a paperweight on the cemetery superintendent’s desk Photograph: Luc Novovitch/Alamy

Heptonstall, West Yorks

Poets’ graves can often become shrines - over and above other writers for reasons which are debated- but Sylvia Plath’s has resembled a battleground. It is less the line of verse on the tombstone (“Even amidst fierce flames the golden lotus can be planted” –not one of hers) that has caused this plot to be so contested. It was the decision by her estranged husband, Ted Hughes, to include his own surname after hers. Plath’s admirers, who blamed him for her suicide, would regularly chisel this off, and then, when Hughes removed the stone for repairs, accused him of trying to hide her memory so as to enhance his own. Finally the word Hughes was cast in bronze to deter the defacers Photograph: John Morrison/Alamy

Forest Lawn, California

Writing your own epitaph can be hazardous, not least if your relatives ignore or amend your exit lines, but double Oscar-winning actress Bette Davis, celebrated for her acerbic wit, managed it. Her choice, “She did it the hard way”, is emblazoned on her white marble sarcophagus in Forest Lawn, the “cemetery of the stars” in Hollywood Hills. Spike Milligan’s arguably was funnier – “I told you I was ill” (in Gaelic); Billy Wilder’s strained for effect (“I’m a writer but then nobody’s perfect”) ; Dorothy Parker had requested “Wherever she went, including here, it was against her better judgement", but ended up with just her name and dates. US TV host Merv Griffin’s takes some beating. He wanted “Stay Tuned” but his family opted for a variation on his catchphrase – “I Will Not Be Right Back After This Message”. Photograph: PR

Westminster Abbey, London

Down the ages church authorities have maintained – and in some places continue to maintain – an often-resented veto on the style of memorials and in particular on the “proper” wording used on them. In the case of Isaac Newton, though, their vigilance may (intentionally or not) have paid dividends. This vast marble monument to the great man includes an inscription that binds religion and science pretty tightly together in a way that sounds a little odd in our own more polarised– but imagine how much more offensive Richard Dawkins would find it had Newton’s admirer, Alexander Pope, been allowed to include, as he wanted, , the triumphant epitaph he had penned: “Nature and Nature’s laws lay hid in night; God said, ‘Let Newton be!’ and all was light.” Photograph: Hemis/Alamy

Cimitero Acattolico, Rome

There are angels aplenty in most graveyards, symbolically linking heaven and earth, but this dramatic life-size winged figure speaks more of the pain of those left behind. Collapsed, weeping and draped over the tomb, it is one of the most copied images in the world, made in 1895 by the American sculptor and long-time Rome resident, William Wetmore Story as a monument to his dead wife, Emelyn. Versions can be seen in cemeteries in the US, Canada, Costa Rica, Luxembourg and Cardiff, plus a noted one at Stanford University in California. And it has been employed to add a Gothic twist to record covers, including the Grammy award winners Evanescence, as well as featuring in 2012 horror film The Woman in Black Photograph: Martin Norris Travel Photography/Alamy

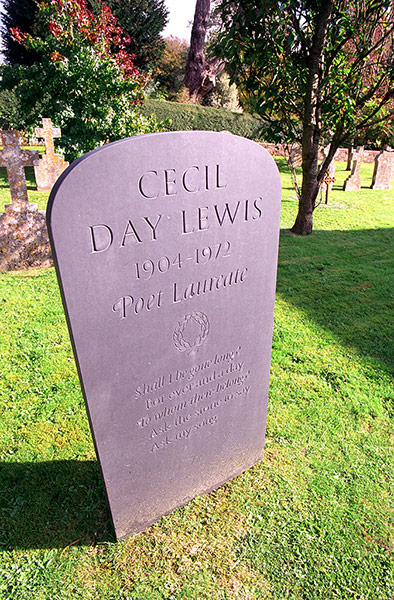

Stinsford, Dorset

The fascination with poets’ graves is given a twist here by a complicated private life. Day-Lewis, poet laureate until his death in 1972, was buried alongside his hero, Thomas Hardy, in this Dorset churchyard, despite being in his own words a “churchy agnostic”. On his tombstone are engraved lines from one of his poems: “Shall I be gone long?/ For ever and a day./ To whom there belong?/Ask the stone to say./ Ask my song.” The final payoff, “Quick, Rose, and kiss me”, is omitted. Such a reference to his lover, the novelist Rosamond Lehmann, for whom he wrote the poem, would have sat awkwardly given that his widow, the actress Jill Balcon, is now also buried in the same grave, ith a stone of her own Photograph: Jack Sullivan /Alamy

Stratford-upon-Avon, Warks

The curse of grave-robbers dates all the way from the pyramids to the “resurrectionists” who in the early 19th century would supply colleges training future surgeons with bodies for students to practise on by disturbing the recent dead. So much so that some cemeteries built watchtowers or offered “mortsafes”, lockable iron cages to place over graves (still to be seen in situ in some Scottish kirkyards). Others opted for a warning on the tombstone, as may be the case with Shakespeare’s grave, inside Holy Trinity Church Stratford-upon-Avon. His dates (1564-1616) are followed by a verse that ends: “Bleste be the man that spares thes stones, And curst be he who moves my bones.” Photograph: Matthew Banks /Alamy

Amherst, Massachusetts

Dickinson arguably wrote more about death and immortality than any other poet. She even left strict instructions as to the manner of her burial, having lived for many years in her family home as a virtual recluse. She wanted her coffin, she said, to be carried through a field of buttercups. But on her simple stone there is no stanza from her works, just the words “Called Back”, reflecting her strong Christian faith. The vast majority of her works may not have been published – or indeed found – until after her death in 1886 but the less-is-more approach to this poet’s grave has contributed to it becoming a place of pilgrimage Photograph: Alamy

Père-Lachaise, Paris

Divine judgment in eternity rubs up against the more tangible verdict of subsequent generations in Père-Lachaise for this is the “celebrity cemetery” sans pareil. Some residents believe that just being buried here alongside big names makes them immortal. Others, though, still feel the need to strain to catch the eye. The monument to Baron Félix de Beaujour (1765-1836) looks like an ill-disguised crematorium tower, but its inspiration was a brief revival in the 1830s of the appetite for “tower-tombs”, themselves loosely based on a reworking of the pyramids, and first seen in ancient Rome. Its purpose was to announce Beaujour (a diplomat by trade) as a man history would remember. And it has – though only for having the tallest monument in Père-Lachaise Photograph: PR