Terry Zwigoff, 1994

I have a weakness for films that examine in-depth the lives of one-off eccentrics. Robert Crumb is a towering genius, as a draughtsperson, as a storyteller and as a creator of cults, and this film gets close to the origins of his ideas and the inner world he inhabits. The story of his family, especially of his relationship with his brother Charles, is heartrending; the transformation of his pain and self-consciousness into epoch-defining art is thrilling; getting to simply watch him draw is a pleasure. I can watch this over and over again. While doodling. Badly Photograph: Ronald Grant Archive

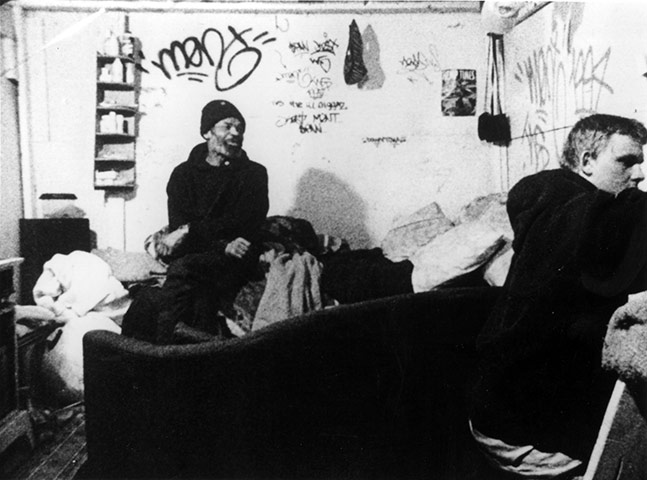

Marc Singer, 2000

Where is Marc Singer? What happened to him? He made one of the greatest documentary films of all time, and then vanished. He was not even a trained film-maker when he made this, which perhaps explains why he was reckless enough to undertake it. While living in New York he heard that there was a community of homeless people living in tunnels under the city, and decided that a film about them might draw attention to their way of life and get them out of there. What resulted was a beautiful and absorbing portrait of an alternative society Photograph: Palm Pictures

Albert Maysles, David Maysles, Ellen Hovde, Muffie Meyer, 1975

Fashion people love this film, and the recent HBO dramatisation with Drew Barrymore raised its profile even more – but its trendiness should not be permitted to detract from its greatness. “Stranger than fiction” is a cliché, but this one did unearth a narrative no screenwriter could have dreamed up. Decayed aristocrats Big Edie and Little Edie Beale initially seem prickly and peculiar, but as the film goes on you fall in love with them; ultimately this is one of the kindest, oddest and most memorable portrait films ever made Photograph: Albert Maysles

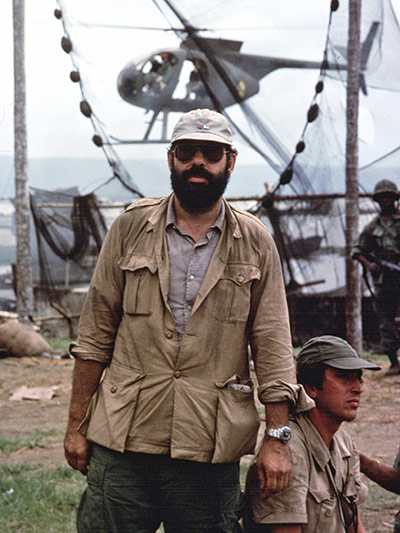

Eleanor Coppola, 1981

The making of Apocalypse Now is one of the epic myths of cinema – an extraordinary combination of personalities, an unbelievable pile-up of crises, and most improbably of all, a masterpiece at the end of it all. This account by Francis Ford Coppola’s wife is at once cool-headed and disarmingly open about the effect upon her and upon her relationship with her husband. Intimate, riveting, and required viewing for any film-maker who thinks he or she is having a bit of a tough time on set Photograph: Everett Collection/Rex Features

Dziga Vertov, 1929

A bravura technical exercise that pushes the potential of cinema to extremes that are still exhilarating today. Vertov (a pseudonym, meaning “spinning top”, for Denis Kaufman) wanted to divorce cinema from theatrical and literary conventions and create a new type of narrative that attained truth through montage. He was terribly solemn about this project, and the film - a collage of images portraying a day in the life of the Soviet Union – functions as a study of the possibilities of documentary observation, but it’s also shot through with charm and humour Photograph: Rex Features

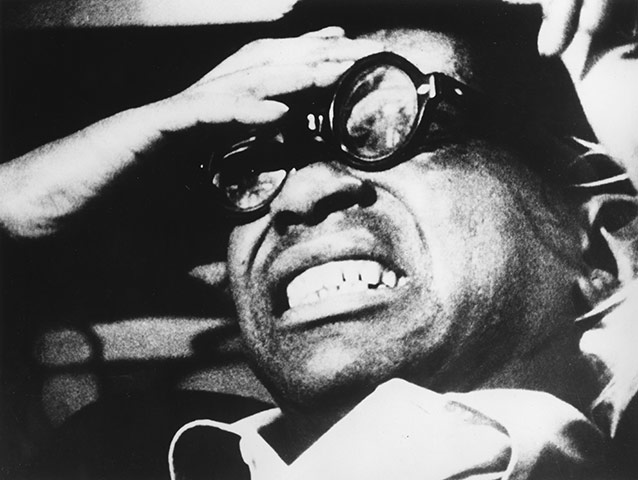

Shirley Clarke, 1967

An unforgettable character study by one of the great avant-garde film-makers of the 20th century. Her subject, Jason Holiday, is a middle-aged African-American hustler who performs the story of his life for the camera with an astonishing mix of sorrow, bravado and high camp pantomime. His account is incredibly revealing about hidden American lives, but it’s also a breathtaking extended performance; like Grey Gardens’s Little Edie, he’s a construction of borrowed mannerisms and tics, elaborately fake but entirely sincere. Clarke, meanwhile, is unsentimental and not averse to goading her subject from off-camera Photograph: BFI

This was made for TV, but it’s probably the documentary I reference most frequently in my head, because of how eloquent it is about film-making and the artistic process - and because it examines one of my favourite artists. It was made during the filming of Lost Highway, but it’s not a simple behind-the-scenes: it approaches David Lynch as a contemporary multi-discipline artist, and addresses his painting and photography and his engagement with the world and his collaborators. Like its subject, it is a mix of curiosity, warmth, generosity and loopy humour Photograph: PR

Jessica Yu, 2007

Plenty of films, including some listed here, centre upon subjective accounts of extreme life experiences. Jessica Yu extends the principle by deconstructing the stories told by her four subjects according to the rules of dramatic structure laid down by Euripides. Four life stories – those of a bank robber, a gay man who has tried to “cure” himself via evangelical Christianity, a terrorist and a victim of childhood bullying – are analysed according to their structure. The intriguing implication is that dramatic structures and sequences are somehow inherent in human lives Photograph: PR

Tim Hetherington, Sebastian Junger, 2010

There is of course a huge body of documentary work around the military experience, but this new film is bold enough to render many of its predecessors irrelevant. The directors – a war photographer and war-zone reporter respectively – spent 15 months embedded with a platoon of soldiers in the Korengal valley in Afghanistan, and have provided a fiercely frank account of the troops’ efforts to win hearts and minds while in fear for their lives. Whatever your take on the politics, this film allows a fascinating proximity to figure on both sides Photograph: Tim Hetherington

Chris Marker, 1983

Not technically a documentary – more accurately an essay, or a collage – but I’ll take any excuse to talk about it. And it’s interesting in the context of documentary, because it is a study of the process of recording, and of the elusiveness of truthful recollection. The narrator collates words and footage supposedly sent to her by an intrepid world traveller; the resulting patchwork of ideas and images is enchanting and confounding and ultimately incredibly life-affirming. For a long time it was very hard to get hold of, but – O brave new world – you can now watch it free on Google Video Photograph: Ronald Grant Archive