Thailand goes to the polls on Sunday to elect the country’s fourth leader in three years amid a tumultuous period of political instability and an ongoing border crisis with rival neighbour Cambodia.

The 8 February election will test whether the country can finally break a cycle of political instability that has lasted more than a decade, marked by a succession of short-lived governments toppled by the military and the courts.

Two major opinion polls released last week showed the opposition People’s Party in pole position, with its prime ministerial candidate Natthaphong Ruengpanyawut the top choice for voters nationwide. A key reason for Ruengpanyawut’s popularity, according to the polls, is his youth. He is 38.

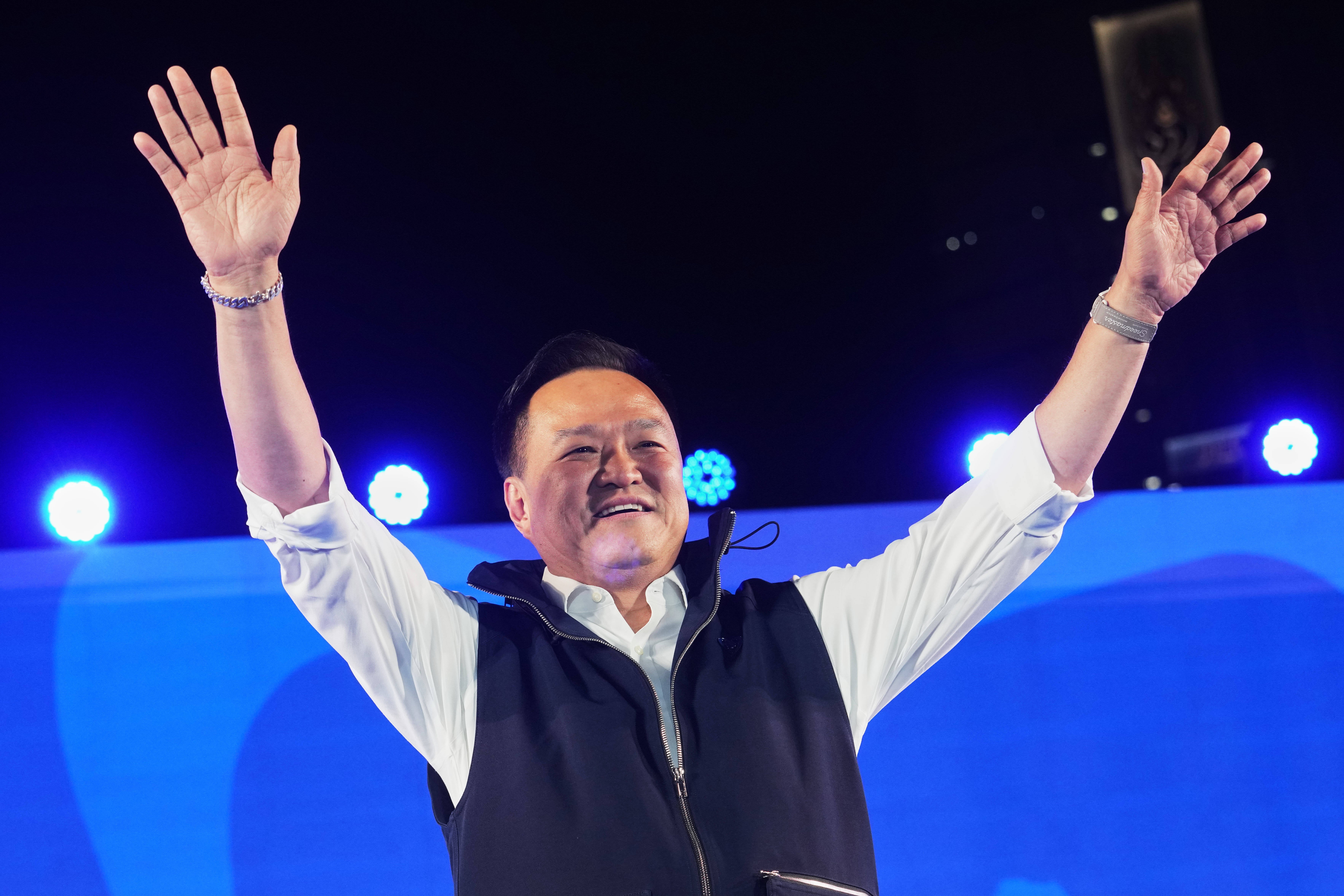

This means caretaker prime minister Anutin Charnvirakul is facing a strong challenge to his hold on power.

The election comes even as Thailand’s democratic credentials remain under scrutiny. The Southeast Asian country has experienced 12 successful coups since 1932. Since the latest transition from military rule in 2019, It has already held two elections.

Thailand was categorised as an electoral autocracy in the 2025 Democracy Report published by the advocacy group V-Dem. Freedom House reached a similar verdict, rating the country “Not Free” and citing democratic reversals such as the dissolution of the Move Forward Party and the removal of Pheu Thai prime minister Srettha Thavisin in August 2024 by the Constitutional Court.

Why does the election matter?

The snap election was called after Charnvirakul dissolved the lower house of the parliament on 12 December to prevent his Bhumjaithai Party’s minority government from being ousted in a potential no-confidence vote.

Charnvirakul, 59, was Thailand’s third prime minister since 2023. He had taken office only in September after Paetongtarn Shinawatra was removed by the courts over a scandal involving a leaked phone call with a Cambodian leader. Shinawatra had been prime minister for only about a year.

The election is seen as a three-way fight between the royalist-military establishment represented by the Bhumjaithai Party, the progressive opposition led by the People’s Party, and the populist Pheu Thai Party linked to the powerful Shinawatra clan.

What’s the election process?

Thailand’s election gives more than 53 million eligible voters the opportunity to decide the make-up of the 500-seat House of Representatives. While 400 seats are filled through constituency races under a first-past-the-post system, the other 100 are distributed to the contesting parties based on proportional representation.

Parties can submit up to three prime ministerial candidates each.

The newly elected lawmakers will then vote to pick the next prime minister. A simple majority is needed for the prime minister to win but close to 270 votes are needed to form a stable government.

The Senate, which is dominated by pro-establishment conservative lawmakers, will have no say in choosing the prime minister.

This marks a break from the last election in 2023, when a military-appointed Senate was able to vote alongside elected lawmakers and block the reformist Move Forward Party from forming a government despite its election victory.

After the 2014 coup, the military introduced an appointed Senate when it changed the constitution, allowing it to handpick lawmakers who ensured junta leader Prayuth Chan-ocha became prime minister after parliamentary elections resumed in 2019. That veto power expired in 2024.

Nationwide referendum

On Sunday, Thai voters will not only vote to elect the new leader, they will also decide, via referendum, whether a new constitution should replace the 2017 charter that was drafted under military rule.

The referendum is the outcome of a decades-long struggle between the pro-military royalist establishment and the popular democratic political movement.

The ballot will ask “Do you approve that there should be a new constitution?” and offer a choice of “Yes”, “No” or “No opinion”.

A majority “Yes” vote would give the parliament the public mandate to begin drafting a new national charter.

A majority “No” vote will leave intact the current constitution, which took effect in 2017 after being drafted by a military-appointed panel following the 2014 coup.

Two previous referendums, in 2007 and 2016, differed from the approaching exercise as they sought approval of drafts written after military coups.

Who are the main contenders?

Charnvirakul of the Bhumjaithai Party is backed by the royalist-military establishment.

He landed the top job as caretaker last year by outmanoeuvring the Pheu Thai Party just hours after a court sacked Shinawatra as the prime minister.

Bhumjaithai has long played the role of kingmaker, operating as a junior coalition partner across Thailand’s polarised spectrum.

More recently, it has sought to sharpen its identity as the country’s dominant conservative force, drawing closer to the military and striking a more overtly nationalist note, particularly as border tensions with Cambodia have resurfaced.

Long regarded as a mid-sized party, it has campaigned on promises of a short-term economic stimulus, decentralisation to allow local governments more control over their budgets, and increased public spending on infrastructure as well as public health.

The People’s Party of Ruengpanyawut is the latest incarnation of the progressive movement that first surged with the Future Forward Party and later the Move Forward Party.

Formed after a court dissolved Move Forward in August 2024, the party has positioned itself as the main opposition force to the conservative establishment.

It focuses on constitutional reform to curb the influence of the military and the courts, reducing the power of big conglomerates, overhauling the bureaucracy and expanding social welfare.

Drawing strong support from younger and urban voters, the People’s Party has leaned heavily on digital campaigning and grassroots mobilisation while continuing to test the limits of Thailand’s tightly constrained political space.

Its leader, Natthaphong, is a former businessman and software engineer who ran a cloud services firm after graduating from university.

He is the country’s youngest leader of the opposition.

Yodchanan Wongsawat, 46, of the Pheu Thai Party is the son of Somchai Wongsawat and a nephew of Thaksin Shinawatra, both former prime ministers. Shinawatra is also the patriarch of the billionaire Shinawatra clan, founders of the Pheu Thai Party and a dominant force in Thai politics for most of the past 25 years.

Pheu Thai, a populist party, was relegated to the opposition bench after then leader Paetongtarn Shinawatra was removed by the Constitutional Court as prime minister for violation of ethical standards.

The party has a strong rural base and benefits from its association with the Shinawatra political brand and network.

Pheu Thai has long been known for its populist cash-transfer schemes, though critics have questioned their fiscal sustainability.

Yodchanan is a political novice. An engineer by training, he spent most of his years in academia as a professor in biomedical engineering at Bangkok's Mahidol University.

He has described himself as “a very small guy on the shoulders of a giant”, a reference to his uncle, the polarising tycoon Thaksin Shinawatra, who is currently in jail.

Former prime minister Abhisit Vejjajiva has energised the Democrat Party, which could alter what appeared to be the three-way contest.

Thailand's oldest political party had long dominated the south and Bangkok before sliding into decline after the military coup in 2014.

Despite the goodwill, Abhisit is unlikely to get enough support to become prime minister, a survey last week showed.

The nationwide survey by Suan Dusit Poll at Suan Dusit University, released on Friday, showed the People’s Party leading in both party-list and constituency support.

The survey conducted between 16 to 28 January showed 36 per cent of people voting for the People’s Party, 22 per cent for Pheu Thai Party and 18 per cent for Bhumjaithai.

Additional reporting by agencies.

Wild elephant kills tourist exercising near his camp in Thailand national park

Airports reintroduce Covid-style checks after deadly Nipah virus outbreak in India

Malaysian restaurant closed after video shows staff ‘washing leftovers for reuse’

Vietnam’s military has been ‘secretly planning for US invasion for 50 years’

Indonesia lifts ban on Grok but AI tool to remain ‘under strict supervision’

Yvette Cooper warns of ‘dire’ crisis in Myanmar, five years on from coup