Thailand’s top political parties are wooing more than 14 million farmers, the single-largest group of voters, with promises such as suspending crop loans and measures to triple their income in four years.

Pheu Thai, a party that has deep roots among Thailand’s rural and farm community and is leading in pre-poll surveys, plans to halt payment of interest and principal on farm loans for three years if it wins the May 14 general election. The debt freeze will allow 7.4 million farmer households to save money for fresh investment, the party said.

It also promised to transfer ownership of an estimated 50 million rai (8 million hectares) to debt-ridden farmers, which will give them new access to credit by using the land as collateral. Move Forward, another opposition party that’s also gaining in surveys, has vowed to confer land titles for about 40 million rai.

Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-Ocha’s United Thai Nation said it will set up a fund to support agriculture product prices, while Deputy Prime Minister Anutin Charnvirakul’s Bhumjaithai party, which has gained in popularity with its successful push to liberalize cannabis and is promoting it as a cash crop, is pledging to guarantee crop prices.

Thailand’s farming heartland in the north and northeast have become key battlegrounds as they can influence the outcome of the election to about 175 seats to the 500-member House of Representatives. How political parties deal with the issue also has ramifications for the global food security and inflation, with the country being a major supplier of rice, sugar and rubber to the global market.

While the Thai government spends about 150 billion baht ($4.4 billion) annually to support crop prices, insurance and other benefits for farmers, slumping prices of rice, rubber, sugar and palm oil over the years amid rising fertilizer and pesticide costs have pushed them deeper into debt.

Efforts by political parties in the past to improve the lot of farmers have at best yielded mixed results. A policy to purchase rice at above-market price from 2011 by then Pheu Thai-led government under Yingluck Shinawatra saddled the nation with millions of tons in stockpiles and cost more than $15 billion.

Distorting Markets

It also distorted the global market, with Thailand unable to export much of the high-priced grain and having to use them as cattle-feed. Yingluck’s government was toppled in a 2014 coup and she fled the country three years later rather than face jail in a criminal case related to the rice program. Her brother, Thaksin Shinawatra, an enduring yet polarizing figure in Thai politics whose term was marked by allegations of corruption, backs Pheu Thai.

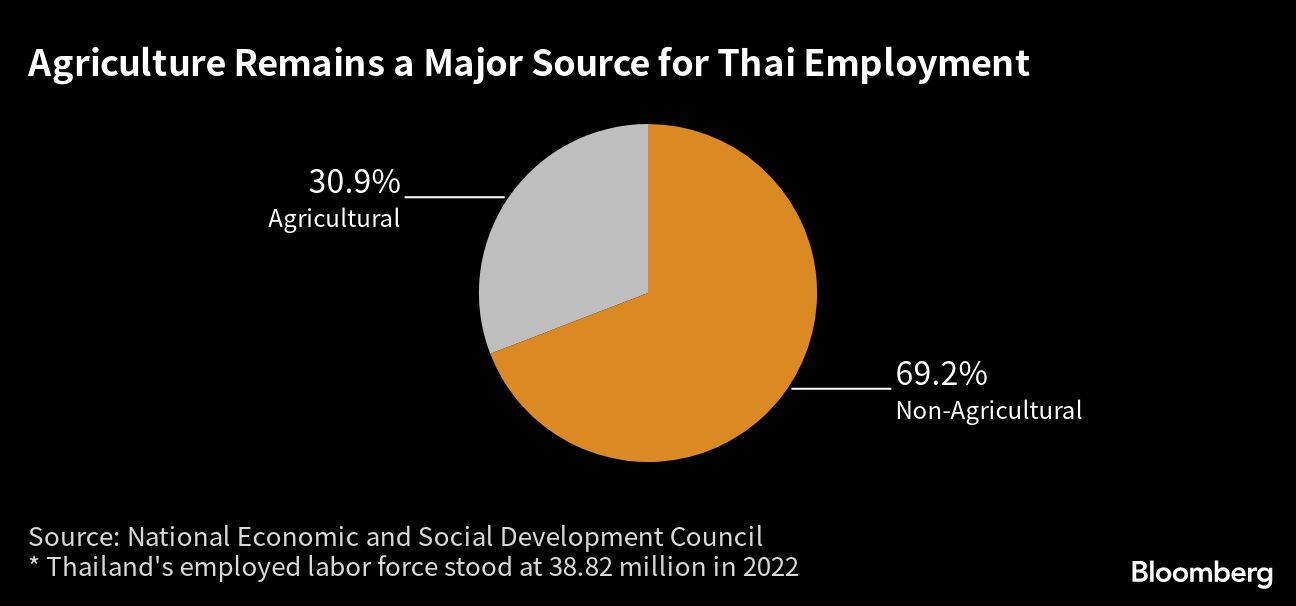

Agriculture, which employs about a third of the nation’s total workforce of about 40 million, has seen its share in the nation’s economy steadily shrink over the past decades with low crop prices, soaring input costs and mounting debt. The sector accounts for about 8% of gross domestic product now, down from about 36% in the 1960’s.

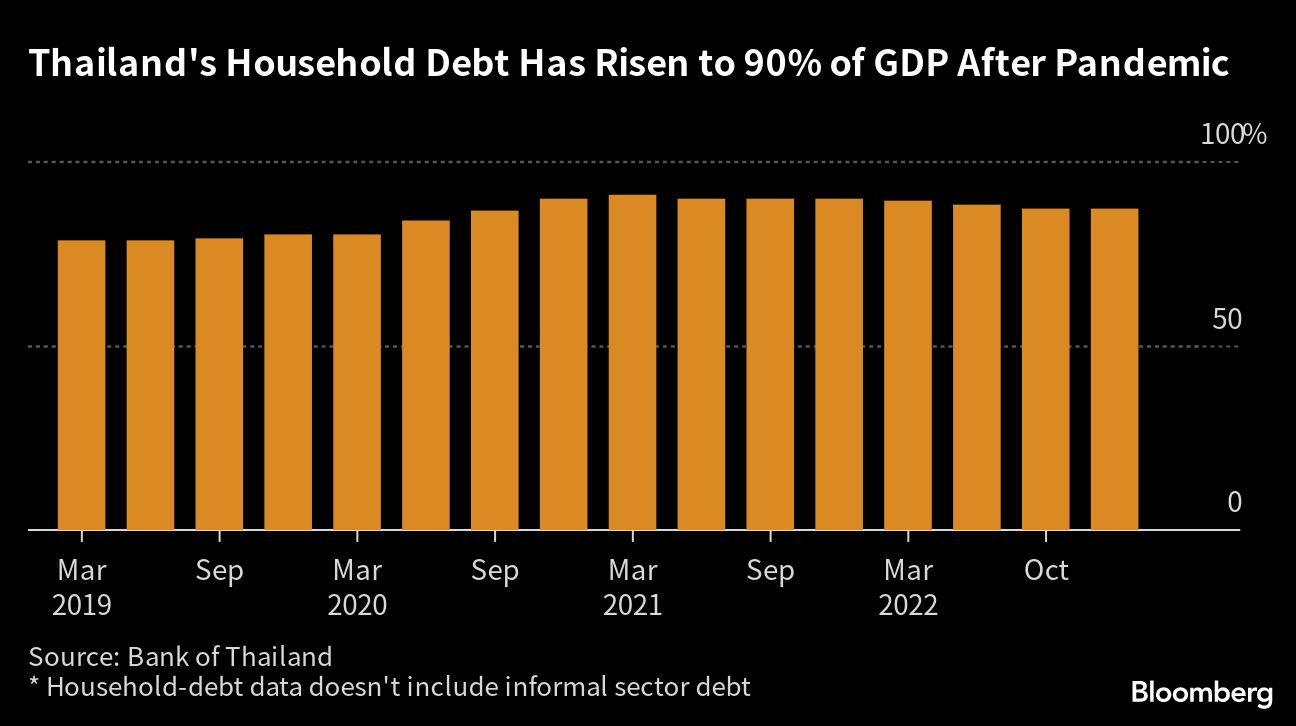

More than 90% of Thai farmer households are indebted at an average of 450,000 baht, and the vicious cycle of debt and reliance on credit to overcome the burden pushes them into a trap, according to a study by the Puey Ungphakorn Institute of Economic Research.

If all the farm support measures announced by major parties are to be implemented, it may cost as much as 300 billion baht, according to Nipon Poapongsakorn, distinguished fellow at the Thailand Development Research Institute.

The way out of the debt trap, according to the Puey Ungphakorn study, is not moratoriums but creating a rural financial market that works, ensuring households can repay while lifting farm income through value addition.

“Debt moratorium policy has been implemented every year. This hasn’t addressed farmers’ debt problem, but rather compounds it,” Nipon said.

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.