How can work style reform be implemented for doctors, for whom long working hours have become common practice? A commission of experts under the Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry is aiming to compile a final report on this matter by the end of fiscal 2018.

There are many issues to deal with: how to advance reform under the Medical Practitioners Law, which legally obligates doctors to provide medical treatment unless there are due reasons to refuse; how to regulate overtime; and a shortage of staff at local hospitals and emergency medical services. We asked three people for their viewpoints: a hospital administrator and representatives of a doctors union and a patients organization. The following are excerpts from the interviews.

(From The Yomiuri Shimbun, May 10, 2018)

Doctors alone cannot sustain medical services

According to a Yomiuri Shimbun survey, 103 regional core hospitals across the nation were issued recommendations for corrections from Labor Standards Inspection Offices, for such reasons as illegally forcing doctors to work long hours. Many hospitals explained the reason for the overtime work as "doctor shortages," and the survey highlighted anew the serious lack of doctors, not only in rural areas where medical staff are insufficient, but also at large university hospitals and in urban areas.

The excessive workload of doctors has been getting more serious year by year. Grave medical errors can occur at any moment under such circumstances, and a commission of experts under the Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry has started discussing how to solve the problem. It is important to consider how to preserve community-level medical services when reviewing doctors' work style.

Regarding their work style, it is necessary to revise the working system by introducing part-time shifts to resolve unduly long hours. Doctors, like anyone else, cannot handle excessive workloads and need breaks and free time. When it comes to university hospitals, doctors assume roles in research and education, as well as in providing medical treatment. If the lines clarifying those roles remain unclear, the heavy burdens placed on doctors will remain unchanged. There should be concrete discussions focusing on these matters.

It is also essential to look at how the regional medical care system should be managed.

A good case in point is an initiative taken by Iwaki, Fukushima Prefecture. A municipal ordinance enforced last June details the roles of the city, medical institutions and residents in this regard.

Under the ordinance, the city government is responsible for securing doctors and maintaining and enhancing the medical care system, while the medical institutions cooperate and share their duties based on patients' conditions. Residents are supposed to choose appropriate medical institutions based on their symptoms and avoid unnecessarily consulting doctors at night and on the weekend.

The three-pronged structure is designed for cooperation to prevent local medical services from collapsing. Although the ordinance only requires efforts be made, attention should be paid as to how the ideal can be achieved.

In addition, the legal obligation for doctors to provide medical treatment -- which many hospitals cited in the survey as the reason for long working hours -- should be discussed in tandem with the current medical care system. The emergency medical care system was insufficient in the past, but it has improved and individual doctors no longer have to handle every medical case.

The obligation is set to protect patients' rights to receive due medical treatment. The responsibility for preserving that right should not be solely taken by doctors -- it is important that governments and medical institutions play a role as well.

However, it will take time to solve all of these issues. Considering the special characteristics of a doctor's job, the work style reform initiated by the central government allows a five-year extension to implement the amended Labor Standards Law after the law is enforced.

It seems unlikely that the problem of doctor shortages can be resolved, and the necessary reforms for hospitals completed, within the grace period. If changes are implemented too hastily, these reforms could cause the medical care system to collapse. The reforms should be advanced incrementally and steadily to eventually apply the same labor standards for other workers to doctors.

--This interview was conducted by Yomiuri Shimbun Staff Writer Kentaro Tanaka.

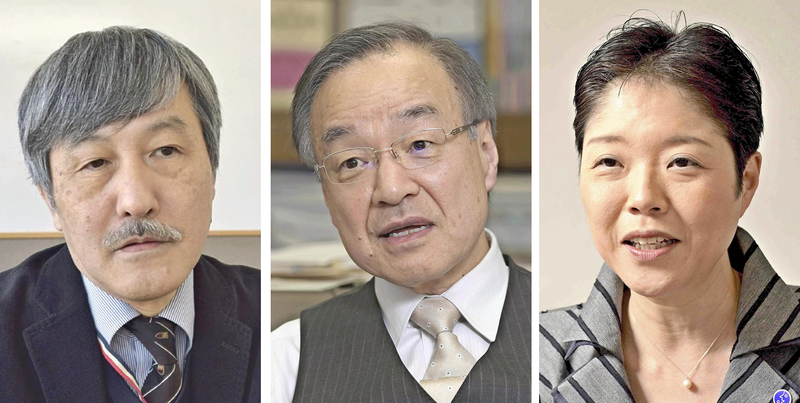

-- Naoto Ueyama / Representative of the National Medical Doctors Union

Graduated from the Faculty of Medicine at Kagoshima University. Established the union in 2009 and assumed his current position. Also serving as a director of the Gyoda-Kyoritsu Clinic, Gyoda in Saitama Prefecture. He is 60.

Capping working hours not the solution

St. Luke's International Hospital in Chuo Ward, Tokyo, has been working on doctors' work style reform since receiving a recommendation for correction from a Labor Standards Inspection Office in 2016.

The inspection office pointed out two main problems. First, the working hours for doctors were simply too long. Although the labor-management agreement at the time restricted overtime work to 80 hours a month [it is currently set at a maximum of 180 hours], doctors' records show it exceeds 200 hours.

We reduced the number of personnel for night shifts, drastically limited the treatment we provide on Saturdays, and stopped consulting with patients' family members both at night and on holidays. We've received complaints, but we've been working on gaining understanding by explaining our situation to everyone with concerns. It took about six months to reduce monthly average overtime, which was almost 100 hours, to about 40 hours.

Second, we had to manage night and day shifts on holidays. We decided to categorize them as overtime that comes with extra pay, instead of paying across-the-board allowances.

The experts commission of the ministry has been discussing restricting doctors' working hours. Needless to say, it is important to manage doctors' own health. But I have some strong concerns that unrealistic conclusions might be reached if the commission considers the matter without properly understanding the reality of the medical field.

Many doctors are accustomed to going to the hospital shortly after 6 a.m. and leaving around 7 p.m. or 8 p.m. at the earliest. Medical interns are called residents in the United States, and in keeping with that title, they work and study as if they actually live at the hospital. When I was younger, I worked overnight shifts two to three times a week and sometimes stayed at the hospital for two months, not stepping out of it even once.

In the United States, medical errors caused by overwork led to limiting interns' weekly working hours to up to 80 hours on average. A research paper published in the United States concluded that these restrictions have adversely affected the quality of medical care for patients and harmed interns' skills.

It is, of course, not good to stay at a hospital for an unnecessarily long time. However, setting time limits collectively brings about negative effects. Physical conditions differ among doctors, and therefore more attentive health management for each doctor should be prioritized.

First of all, the central government has not calculated the number of doctors needed regionally and in each specialized field, nor has it educated or trained enough doctors. Abruptly presenting an argument based on idealism will just demoralize people in the medical field.

The number of doctors for emergency rooms are insufficient, even at hospitals with many doctors, including St. Luke's International Hospital. We're recruiting doctors, but we cannot secure them. The situation must be much worse in rural areas.

It does not make sense to demand limits on working hours and at the same time legally obligate doctors to provide medical treatment. The legal obligation should be abolished. Doctors always see patients whenever it is necessary. It comes from their professionalism, not because the law stipulates they have to. The work style of doctors should not be restricted by limiting their working hours. Rather, it is better suited to a discretionary work style, which entrusts much of the decision-making to doctors.

-- This interview was conducted by Yomiuri Shimbun Senior Writer Yoshihiko Tamura.

--Tsuguya Fukui / President of St. Luke's International Hospital

Graduated from the Faculty of Medicine at Kyoto University in 1976. Earned a master's degree at Harvard's T. H. Chan School of Public Health. After serving as a professor at Kyoto University and other positions, assumed his current position in 2005. Also serves as the president of St. Luke's International University. He is 66.

Patients should change their way of thinking

It's not only doctors but also patients who must change their way of thinking, in order to realize work style reform for doctors.

Some inpatients ask for attending doctors to see them, even in the middle of the night. They've become more aware of their rights as a patient and feel entitled to receive a higher level of treatment from doctors, and doctors spend more time talking to patients and their family.

Asking for a consultation from doctors on weekends or at night because patients are busy with work during the day has forced doctors to work long hours. We need to change society so that people can say, "Let me take time off, because I have an appointment to see a doctor for a consultation."

What effects should we expect if we introduce overtime limits on doctors, just as with ordinary workers? Will the medical system be sustainable? Strictly restricting doctors' overtime work in regions that lack doctors would cause the collapse of the community's medical service.

These restrictions should be considered and applied differently in keeping with the situation in each region, such as what sort of medical care is available locally, the size of the hospital and other factors. To become a full-fledged doctor, younger doctors have to learn numerous things. They need to spend time learning the basics, otherwise patients cannot comfortably rely on them.

A legal obligation -- requiring doctors to provide medical treatment unless there are due reasons to refuse -- is one of the factors that have led to long working hours for doctors. However, they are not ordinary workers. Rather, they have a sense of duty to save patients' lives. Doctors must have that kind of mettle.

Simply increasing the numbers of doctors is unlikely to solve the problem. There could be more doctors in urban areas, but the situation in rural areas, which face a shortage of doctors, will not improve. We should start working on practical measures first. Continuing to work after an overnight shift should be reconsidered. No one wants doctors to be tired or sleepless. This is also problematic from a medical safety viewpoint.

It may be effective to put attending doctors on a team system, in which a team of doctors sees patients, instead of one doctor taking charge of a patient. Patients must understand that always asking for the same doctor overextends the doctor and is to their own disadvantage.

Any medical services that can be performed by someone other than doctors should be assigned to other staff, such as nurses, pharmacists or office assistants. In the future, it is likely that artificial intelligence will come to play a larger role in image diagnosis and other areas. Patients and their family members have excessive expectations of doctors, and this needs to change.

It is not well known that doctors are included in the work style reform that the government is promoting. Each person should understand the reality that the current level of medical service is sustained by the long working hours of doctors. We should act sensibly to promote work style reform for doctors, and not demand that doctors do everything for us.

--This interview was conducted by Yomiuri Shimbun Staff Writer Kazuki Nishihara.

-- Ikuko Yamaguchi / Chief Director of the nonprofit Consumer Organization for Medicine & Law (COML)

Joined COML in 1992 after suffering from an illness. Asssumed her current position in 2011. COML conducts telephone consultations and other activities aiming to realize medical service emphasizing patients' values. She is 52.

Read more from The Japan News at https://japannews.yomiuri.co.jp/