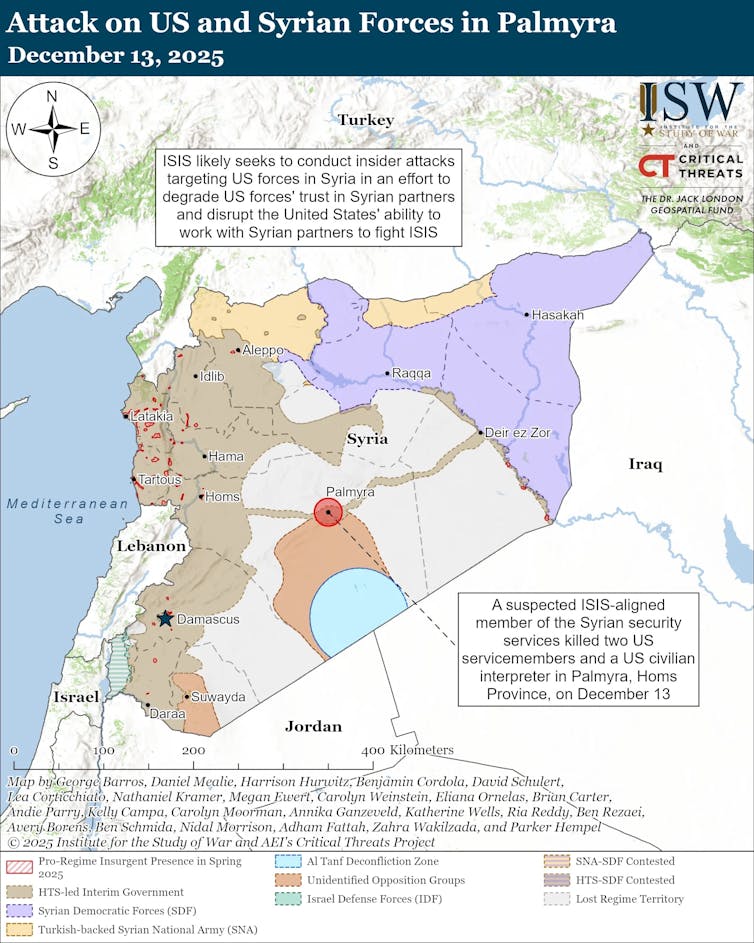

The US military launched a wave of strikes against targets in central Syria on December 19 in response to an attack on US forces near the ancient city of Palmyra one week earlier. That attack saw a lone Islamic State (IS) gunman kill two US service members and one American civilian at a fortified base in the city.

The perpetrator, whose identity has not yet been released, had recently enlisted in Syria’s internal security forces. He had reportedly already attracted suspicion from local security leadership over his possible extremist sympathies.

The attack has exposed deep vulnerabilities within the Syrian transitional government’s security architecture. It also illustrates how IS has adapted from being a territory-holding “proto-state” into an insurgent movement designed to exploit Syria’s institutional weaknesses.

When the regime of Bashar al-Assad collapsed in late 2024, Syria’s new authorities faced the urgent and daunting task of imposing security across a country strained by institutional collapse and a complex network of competing armed groups. The new president, Ahmed al-Sharaa, moved quickly to assemble national security forces.

His government prioritised speed and territorial coverage over comprehensive vetting. Thousands of fighters from diverse former factions were absorbed into new security units in an effort to establish an immediate state presence.

The Palmyra attacker emerged from this process. He was one of roughly 5,000 individuals to be recruited into a desert-region security division. Despite concerns about IS infiltration being raised and the individual concerned being reassigned to guard equipment at the base, the security services were still unable to prevent the attack.

The incident underscores how deeply fragmented Syria’s security landscape remains one year after Assad. Kurdish-led forces, tribal and communal militias, armed Druze groups and remnants of former regime networks continue to operate with varying degrees of autonomy in different parts of the country.

This fragmented environment weakens command structures, complicates accountability and creates openings for infiltration by extremist groups. Security sector reform in such a context should be less about rapid centralisation and more about managing a hybrid and uneven security system. This is something the current transition has so far failed to achieve.

Logic of insurgency

While the Syrian transitional government has struggled to consolidate control and secure its territory, IS has been recalibrating its strategy. Having lost its territorial control in Iraq and Syria in 2019, IS has shifted from governing territory to waging a low-visibility insurgency.

Central Syria’s geography has helped IS adapt. Syrian state forces have struggled to penetrate the desert areas surrounding Palmyra. These areas offer conditions that favour insurgent mobility and concealment, such as difficult terrain and logistical links to former IS strongholds.

The objective of IS is no longer to rule, but to erode the legitimacy of the Syrian authorities. Its attack in Palmyra fits squarely within this logic, occurring as Syria was deepening cooperation with the US-led international coalition against IS. The group’s aim seems to be to disrupt emerging security partnerships and deter further international engagement with Syria.

The Palmyra attack places al-Sharaa’s government in a strategic bind. International partners like the US expect a professional and reliable security apparatus capable of preventing infiltration and protecting joint operations. And in the aftermath of the attack, the recruitment and vetting procedures of Syria’s internal security forces have come under scrutiny.

The US president, Donald Trump, said the attack took place in an area of Syria the interim government “doesn’t have much control over”. Then, a few days later, he added Syria to a list of countries subject to a full US travel ban. Part of Washington’s justification for the move was Syria’s continuing security challenges.

At the same time, the government faces significant domestic constraints. Aggressive purges or the abrupt restructuring of security forces risk destabilising the fragile coalition of armed groups upon which the state currently relies to maintain security, manage territorial control and counter possible threats from remnants of the regime.

It’s possible that rival power centres such as the Syrian Democratic Forces in the north-east or the Sweida Military Council in the south may also seize on the Palmyra incident to argue that the central government is unfit to exercise exclusive control over security. This would strengthen demands for decentralised or autonomous arrangements.

Moving forward, Syria’s transitional authorities will need to perform a difficult balancing act. They will have to accelerate meaningful security reform to satisfy international partners and counter IS, while managing internal power dynamics that remain unsettled and highly sensitive. This tension between reform and survival is precisely what IS seeks to exploit.

The Palmyra attack is a reminder that the defeat of IS’s territorial project did not bring lasting security. Syria’s transition now hinges less on battlefield victories than on the slow and contested process of building credible and accountable security institutions.

Until security reform moves beyond emergency measures and tackles the underlying weaknesses in the Syrian security apparatus, attacks like the one in Palmyra are likely to remain a persistent threat both to Syria’s stability and its international partnerships.

Rahaf Aldoughli's research into armed groups in Syria is funded by XCEPT.

Haian Dukhan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.