We all need myths, whether as a way to better understand the world and humanity or as comfort in face of grief and anguish. A century ago, the artists of the Surrealist movement, battling the trauma of war, also needed myths.

“Mythologies: Surrealism and Beyond – Masterpieces from Centre Pompidou”, which opened on May 21 at the Hong Kong Museum of Art, expounds on these ideas.

The exhibition, curated by Didier Ottinger, deputy director of the National Museum for Modern Art at Paris’ Pompidou Centre, is split into eight sections. It dives into various myths that captured the imagination of Surrealists, from the Minotaur and Chimera to the Surrealists’ own creation, the headless Acephale. The exhibition also includes response works by two Hong Kong artists, Keith Lam and Hazel Wong.

The Surrealists sought to free humanity from the shackles of rational thought and liberate the unconscious mind, which they saw as the source of creativity. One of the figures they looked up to was Sigmund Freud, the Austrian founder of psychoanalysis, who plumbed Greek mythologies to explain human desires and behaviour, Ottinger says. Freud’s hold on the Surrealists can be seen in Luis Buñuel’s 1930 satirical film L’age d’Or (The Golden Age), the title referring to a period of peace and prosperity in Greek mythology. Amid the barrage of surrealist imagery, viewers are served a blistering attack on the Catholic Church and modern society.

In the exhibition, the Minotaur, a half-bull, half-man figure, is simultaneously a figure of excess – seen in Pablo Picasso’s Bacchanal Scene with Minotaur (1933-34), where the creature cavorts with humans – and the loss of reason, epitomised by French artist Andre Masson in The Labyrinth (1938).

Credited for reviving the popularity of the Minotaur myth, Masson has drawn many versions of the Cretan monster and The Labyrinth is his most grotesque. The Minotaur appears as a deformed white husk, with its insides transformed into a labyrinth of stairways, mazes and pylons. Nothing but a shell remains of the once-powerful creature who let repressed desires chip away its insides.

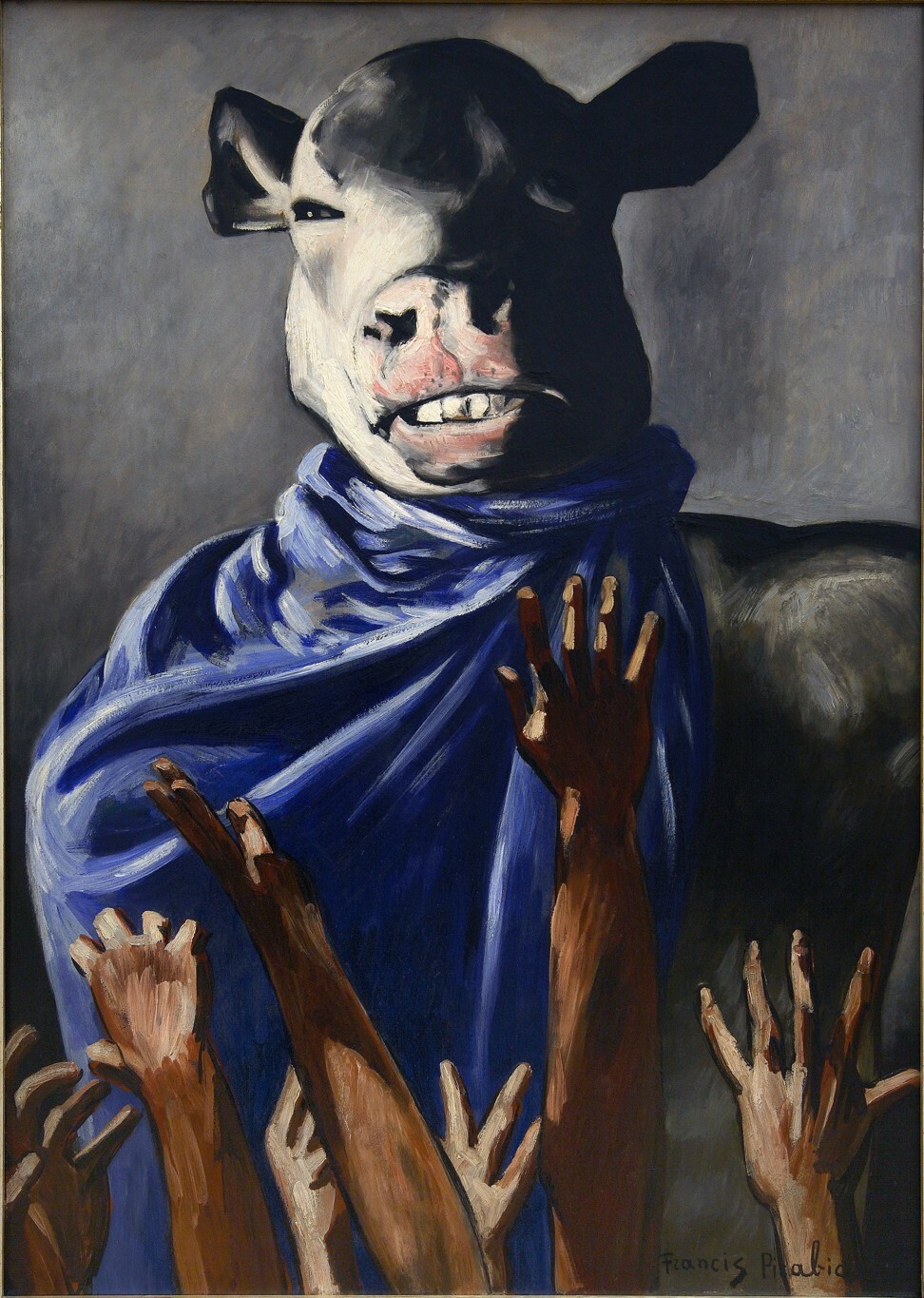

Traditionally, the Minotaur embodied the struggle between the natural and unnatural, but for the Surrealists living through war and devastation, it became a symbol of the loss of humanity, says Apo Wu, curator of learning and international programmes at the Hong Kong Museum of Art. That is reflected in Francis Picabia’s The Adoration of the Calf (1941-42), where expressively rendered hands reach towards a smirking cow-headed creature – a damning critique of the cult of personality surrounding dictators like Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini and Francisco Franco at the time.

At times, mythologies were appropriated by the Surrealists in personal ways. William Tell was a heroic figure in Swiss folklore who rebelled against tyrannical rulers, but Salvador Dali’s William Tell (1930) bears little resemblance to the original, instead appearing as a father figure who menacingly wields a pair of scissors. Opposite him is a youth hiding his face behind his hand, his genitals covered by a leaf. One can guess at what transpired between the two. Is Dali depicting his own father – who he saw as an overbearing figure – or was the image a metaphor for the fascism sweeping across Europe at the time?

The Surrealists also sought to create a new myth unique to the tumultuous times they lived in.

In 1936, French writer Georges Bataille created a journal called Acephale that aimed to liberate man from rational thought. On the cover was a headless creature clutching a dagger in one hand and a burning heart in the other, with a skull covering its groin. Masson’s visual representation of the Acephale, it served as an antithesis to Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, the embodiment of classical reason.

The Acephale section of the exhibition features plenty of headless creatures. There is Alberto Giacometti’s Woman with Her Throat Cut (1932), a bronze sculpture depicting a body slit open. There is also Hans Bellmer’s photographic series, The Games of the Doll (1938-49), which features dolls in different stages of dismemberment behind a sheer red curtain.

By the ’40s and ’50s, with the advent of new broadcasting tools, the Surrealists looked to outer space, advertising and Hollywood as the new frontiers of mythologies, Ottinger says.

Embodying this interest is Victor Brauner and Roberto Matta’s Intervision (1955), a painting depicting an assortment of figures, all with bizarrely shaped heads, held captive by a screen.

A lot of the imagery in the exhibition can be challenging, but the essence of Surrealist art should be familiar. After all, we too live in surreal times of rising nationalist rhetoric, the acceleration of tech and of course, Covid-19, which has disrupted our lives like never before.

Lam’s Artificial Reality (2021) is a multi-screen “robot” that analyses and interprets raw images fed into it, finding a connection between surrealism and artificial intelligence.

“Do machines have a subconscious?” the artist asks. “Our subconscious is shaped by experience, and our experience of the world has moved onto digital screens. Is our subconscious ultimately controlled by the machines?”

Her brother died when she was 10. His mother died during his 20s

Opposite this, Wong’s Dreaming in Hong Kong (2021) is an animated film pondering our existence during a global pandemic.

The Surrealists’ mythological beasts evoke Lo Ting, a myth that is uniquely Hong Kong. Created by local artist Oscar Ho in 1997, the creature with the head of a fish and the body of a man captured Hongkongers’ struggle for their own identity around the time of the handover. Given the political events of the past two years, one can’t help but wonder what kind of myth will sufficiently capture the unease underlying so many aspects of people’s lives now.

Mythologies: Surrealism and Beyond – Masterpieces from Centre Pompidou, Hong Kong Museum of Art, 10 Salisbury Road, Tsim Sha Tsui, Kowloon, Mon-Wed, Fri: 10-6pm, Sat-Sun: 10-7pm, closed on Thursdays. Until September 15.