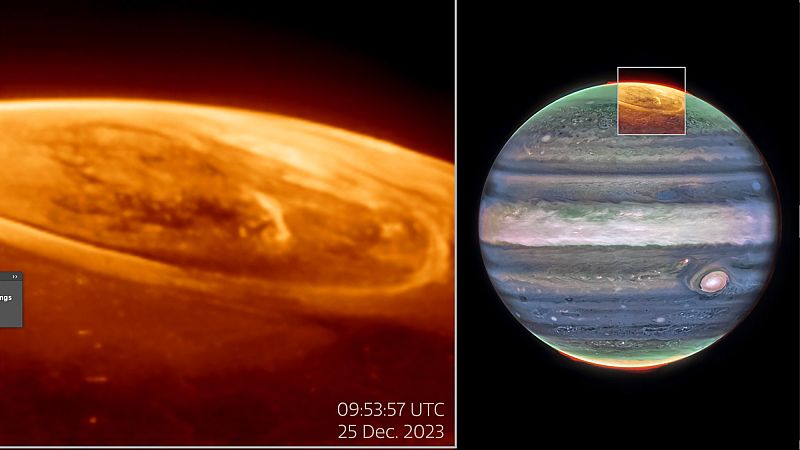

Auroras on Jupiter are hundreds of times brighter than those seen on Earth, new images from the James Webb Space Telescope have revealed.

The solar system's largest planet displays striking dancing lights when high-energy particles from space collide with atoms of gas in the atmosphere near its magnetic poles, similar to how the aurora borealis, or the Northern lights, are triggered on Earth.

But Jupiter's version has much greater intensity, according to an international team of scientists who analysed the photos from Webb taken on Christmas in 2023.

Webb previously captured Neptune's glowing auroras in the best detail yet, many decades after they were first faintly detected during a flyby of the Voyager 2 spacecraft.

How Jupiter's aurora are different from Earth's

Auroras on Earth are caused by charged particles from the Sun colliding with gases and atoms in the atmosphere near the planet's poles, causing streaks of dancing light in the sky.

On Jupiter, additional factors are at play other than solar wind. High-energy particles are also drawn from other sources, including Jupiter's volcanic moon Io.

Jupiter's large magnetic field then accelerates these particles to tremendous speeds, hundreds of times faster than the auroras on Earth. The particles slam into the planet's atmosphere, causing gases to glow.

James Webb has been able to give more details about how they are formed on Jupiter due to its unique capabilities.

The new data and images were captured with its Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) on December 25, 2023, by a team of scientists led by Jonathan Nichols from the UK's University of Leicester.

"What a Christmas present it was – it just blew me away!" said Nichols.

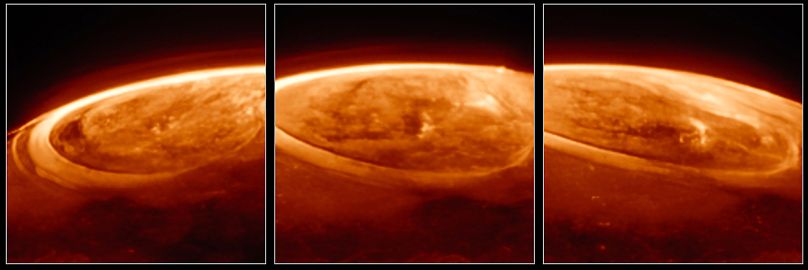

"We wanted to see how quickly the auroras change, expecting them to fade in and out ponderously, perhaps over a quarter of an hour or so. Instead, we observed the whole auroral region fizzing and popping with light, sometimes varying by the second".

The findings were published on Monday in the journal Nature Communications.