In a 2004 essay, the late writer Hilary Mantel considered the story of Gemma Galgani, a 19th-century Italian mystic who refused food, bore wounds on her hands and feet that she claimed were stigmata—a doctor declared them to be self-inflicted with a sewing needle—and believed that enduring periods of intense physical suffering could expiate all the sins ever committed by priests. There is something unnervingly timeless, Mantel writes, about young women who “starve and purge themselves, and … pierce and slash their flesh,” even if we no longer endorse such behavior as spiritual devotion. Galgani was canonized as a saint in 1940. While venerating her, few people noticed that she was terrified of doctors, hated being examined, and wrote once of a servant who “used to take me into a closed room and undress me.” It’s easier, maybe, to believe in miracles than to reckon with the pain of a girl whom someone is quite conventionally hurting.

The question of what people believe in, and what they don’t, is the primary preoccupation of The Wonder, a haunting new Netflix adaptation of a 2016 novel by Emma Donoghue. Set in 1862 in Ireland, shortly after the Great Famine killed about 1 million people, the movie begins as an English nurse, Lib (played by Florence Pugh), travels to a rural part of the country for an unusual commission. Lib has been employed to keep watch over an 11-year-old girl who some locals believe is a living miracle: She has existed, healthily and apparently without eating, for several months. “She’s a jewel,” a visitor says reverently, proffering money to the girl’s parents. “A wonder.”

Lib is a northerner, the kind of stern pragmatist determined to dispel this mystical nonsense. But she’s disarmed almost immediately by the girl, Anna (Kíla Lord Cassidy), who stares at Lib during her first examination with a composure that’s part sullen, part beatific. “I don’t need to eat,” Anna tells her. “I live on manna. From heaven.” The village’s elders want to co-opt Anna for their own ends: The doctor (Toby Jones) sees her as a scientific discovery in the making, a girl who can live like a plant on air, water, and sunshine; a landlord (Brían F. O’Byrne) imagines her as “our first saint since the dark ages.” A journalist sent to investigate the situation, Will Byrne (Tom Burke), declares Anna and her family to be scammers, hoodwinking gullible Catholics for profit. In one scene, the director, Sebastián Leilo, projects Anna’s reclining silhouette against the dark hills of the Irish landscape, making her physical body the backdrop for everyone else’s imaginative theories.

The skies are heavy with rain and pathetic fallacy; rarely does a film feel quite so frigid, so damp to the touch. Hunger is the narrative canvas and the scenery—not just Anna’s but everyone’s. When Lib eats, before and after her watch, it’s with grim efficiency; she piles food onto her fork with something like resentment while the innkeeper’s four daughters silently stare at her. Will is revealed to have lost his entire family to the famine; they nailed the door of their home shut rather than suffer the indignity of dropping dead in the street. Lib finds Anna’s prolonged fast hard to parse: She initially seems healthy enough but soon begins to deteriorate under Lib’s strict oversight. “She’s dying,” Lib tells Anna’s mother furiously. “She’s chosen,” Anna’s mother (Elaine Cassidy) replies, resolute in her belief that although life is brutish and short, heaven and hell are eternal. Everyone except Lib and Will seems curiously numb to the slow death of a child. They’re more inclined to fawn over her discipline and admire the holy spectacle of her self-annihilation.

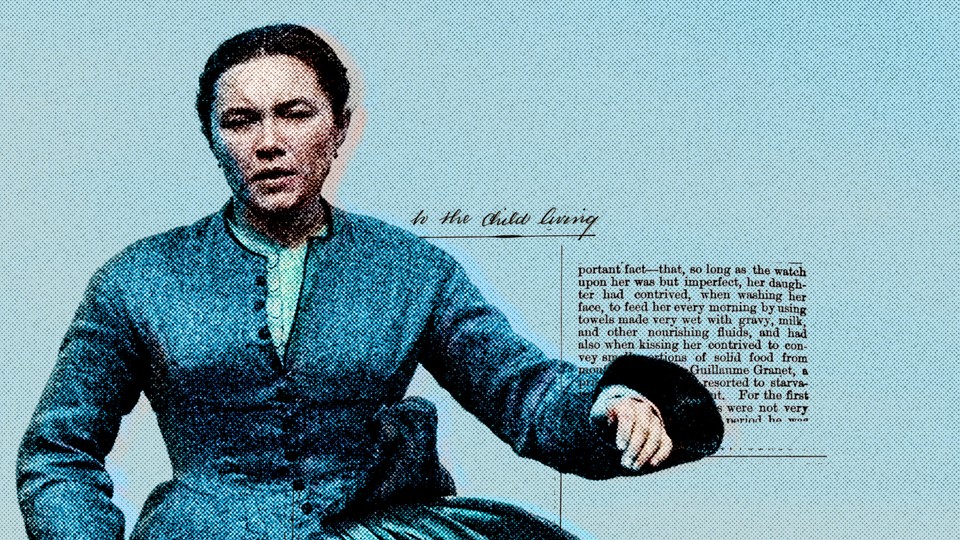

This spectacle, as Mantel’s essay points out, is nothing new. Donoghue writes that she based her book on “almost fifty cases of so-called Fasting Girls”—young women around the world who became famous for supposedly surviving without food. But Anna seems most similar to Sarah Jacob, a Welsh girl in the mid-19th century who claimed to have existed without food since the age of 10 but who died once her fast was put under strict medical watch. Anorexia mirabilis, the condition of refusing to eat for spiritual reasons, is as omnipresent across human history as plague and lice.

Girls have forever sought to reduce themselves for reasons they haven’t always been able to explain. But modern context fills in the gaps. Starving yourself into a state of secondary amenorrhea (whereby a person stops menstruating) is a way to avoid fertility, unwanted marriage, or male desire. (Legend has it that the Italian nun Columba of Rieti was once stripped naked by a gang of men who retreated when they saw the scars from her self-inflicted injuries.) And not eating—as any toddler’s parent knows—is an act of defiance, which is a posture that girls are rarely allowed. The Wonder, thankfully, resists dwelling on Anna’s physical diminishment as the movie progresses (the book is more explicit on that front), but Cassidy’s composed performance conveys that Anna is playing with power. She is stubborn, she is determined, she is dying.

When The Wonder was reviewed as a novel, several critics complained about the revelation late in the book that justifies Anna’s actions, as though it is too humdrum for an otherwise extraordinarily crafted tale. I won’t wholly spoil what happens, but it’s telling that a common crime against girls could be dismissed for being, in Stephen King’s words, “a little too gothic and a little too convenient.” It’s natural, I suppose, to crave a more unusual story—to want to believe in holy magic and mystery instead of in mortal suffering and abasement. But the blessing of The Wonder is how it acknowledges the things we most want to believe and still proposes, in the end, that human acts and faith in others can be the most miraculous things of all.