Akkarawin Krairiksh wasn’t at all surprised by the toxic smog blanketing Thailand’s major cities these past weeks. For him, it was a long time coming.

Over the past couple of years, the freelance photographer has been researching toxic particulate matter to figure out where it comes from, what it looks like and if there is any hope of solving the issue in the future. The resulting images, which he first exhibited half-a-year ago, have never been more relevant than today.

“I wanted to figure out something that was weighing on my heart about my own sickness and health, and my family’s sickness and health,” he said. Akkarawin suffers from respiratory problems and has a family member who developed cancer due to toxic air. “All of it really came from my fear of death. I wanted to know what I had to do for my body to be OK; what I have to do to cope with [the dust].”

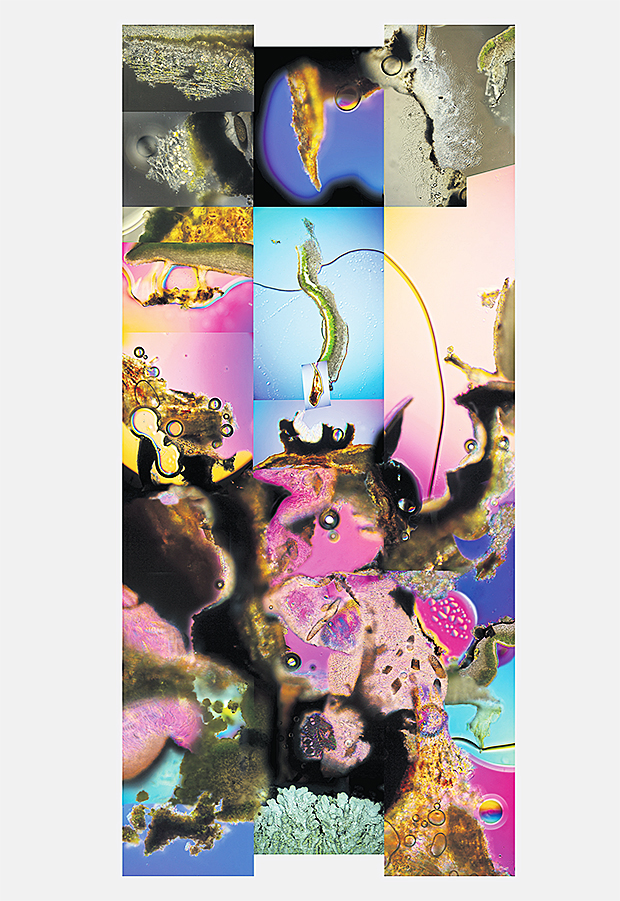

Last year, as part of the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre’s “Early Years Project #3”, Akkarawin built a “dust chamber”, simulating what it would look like inside of a microscope. As visitors walked into the room, they came face to face with enlarged photographs of dust particles and toxic particulate matter displayed on the walls and ceiling. In the middle of the room was a sculpture of a green mass, representing lichens -- a composite organism made up of fungus and an algae or cyanobacterium which is sensitive to pollution and air quality. He named the exhibition “Transforming”.

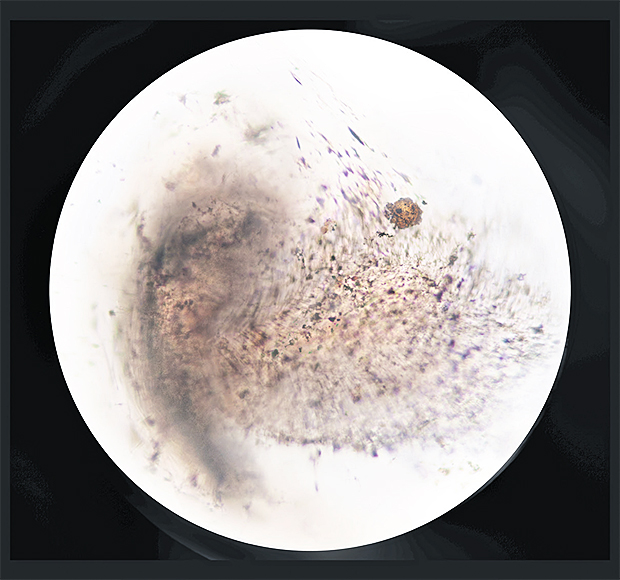

“I wanted to see the physical aspects of dust,” he said. “All of my photographs were taken with a microscope.”

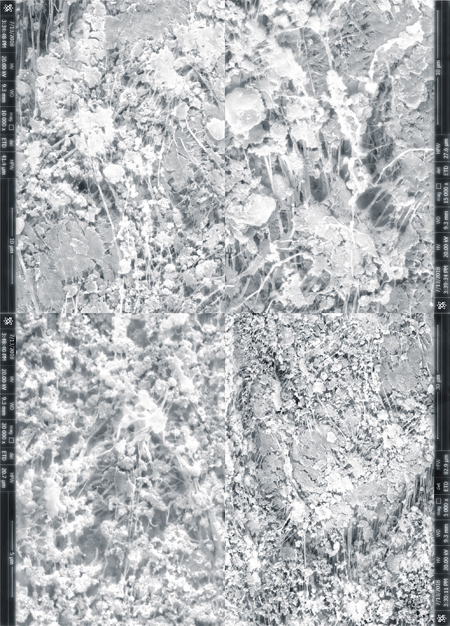

Having shadowed professors from Thailand’s leading universities, Akkarawin was able to take photographs of these floating particles through powerful microscopes. This, he hoped, would help him make sense of them. There is a shot of a filter for PM2.5 (minuscule particulates, 2.5 microns or less in diameter) that would make your skin crawl, and a collage of the larger dust particles PM10 taken on different days to show how air quality can differ from day to day.

PM, short for particulate matter, is a suspension of microscopic solids and liquid particles floating in the air or atmosphere, originating from both natural and anthropogenic sources. The most dangerous ones, of course, result from human activities such as the burning of fossil fuels and crops. Particles like PM2.5 are especially dangerous as they can easily penetrate deep into our respiratory system and cause long term health problems.

“Pollution is going to screw us over in the next 10 years,” Akkarawin said with a rueful smile. “We have to look at how other countries solve this problem. Germany, for example, was extremely cut-throat. They cut the use of diesel fuel altogether. They’re willing to lose profit for the benefit of the people. Everyone has the right to breathe clean air. Can we have this [in Thailand]? This is what I’d like to ask.”

He realises that solving the issue is not as simple as he makes it out to be. Developed countries are doing a better job at tackling issues relating to the environment and air pollution in part because they’ve been dealing with them for longer. And although many countries have cut manufacturing at home, industries have moved their plants to places like India and Southeast Asia instead.

“The easiest thing to do [in Thailand] now is reduce emissions from cars,” Akkarawin added. “We don’t have to meet European standards yet.”

There are also microplastics, something Akkarawin believes aren’t being talked about as much as they should be.

“Microplastics are an extremely scary type of dust,” he explained, “because our bodies do not have preventative measures to filter them out. Microplastic dust is the same size as PM2.5. Rat poison, cancerous chemicals and other toxins are absorbed into microplastics. These microplastics come from bags that have been dried up and dissolved into the air.”

It all sounds incredibly bleak, but not everything Akkarawin saw was negative. During the course of his research, he came across the composite organisms called lichens. Naturally occurring, lichens are extremely sensitive to sulphur dioxide pollution in the air, causing certain species to die or go extinct entirely. Yet, according to Akkarawin, there are a number of lichen species able to survive in the highly polluted city.

Seeing this as a light at the end of the tunnel, Akkarawin created a sculpture in the shape of a lichen and placed it right at the centre of his “dust chamber”.

“What I want to happen with this exhibition is for people to know what the negatives are, but also know how we can adapt,” he said. “I took lichens as a symbol of adaptation. They are usually found in nature, but the lichens found in Bangkok have adapted and are able to survive the poison and smog.

“My own method is to change the way I work.

“If I want to remain healthy I change the way I travel; I select the days on which I go out. [But for office workers] that’s troublesome. The only thing I can do is caution people and they will have to make adjustments to their own lives... Right now it’s hard to do anything. When there are no checks and balances, everything is broken.”

One sure way of making things a bit better, though, is to plant more trees.

“The more plants we grow, the more we’re able to prevent our world from dying,” he said. “Plant now and you’ll see the results in 10 years.”