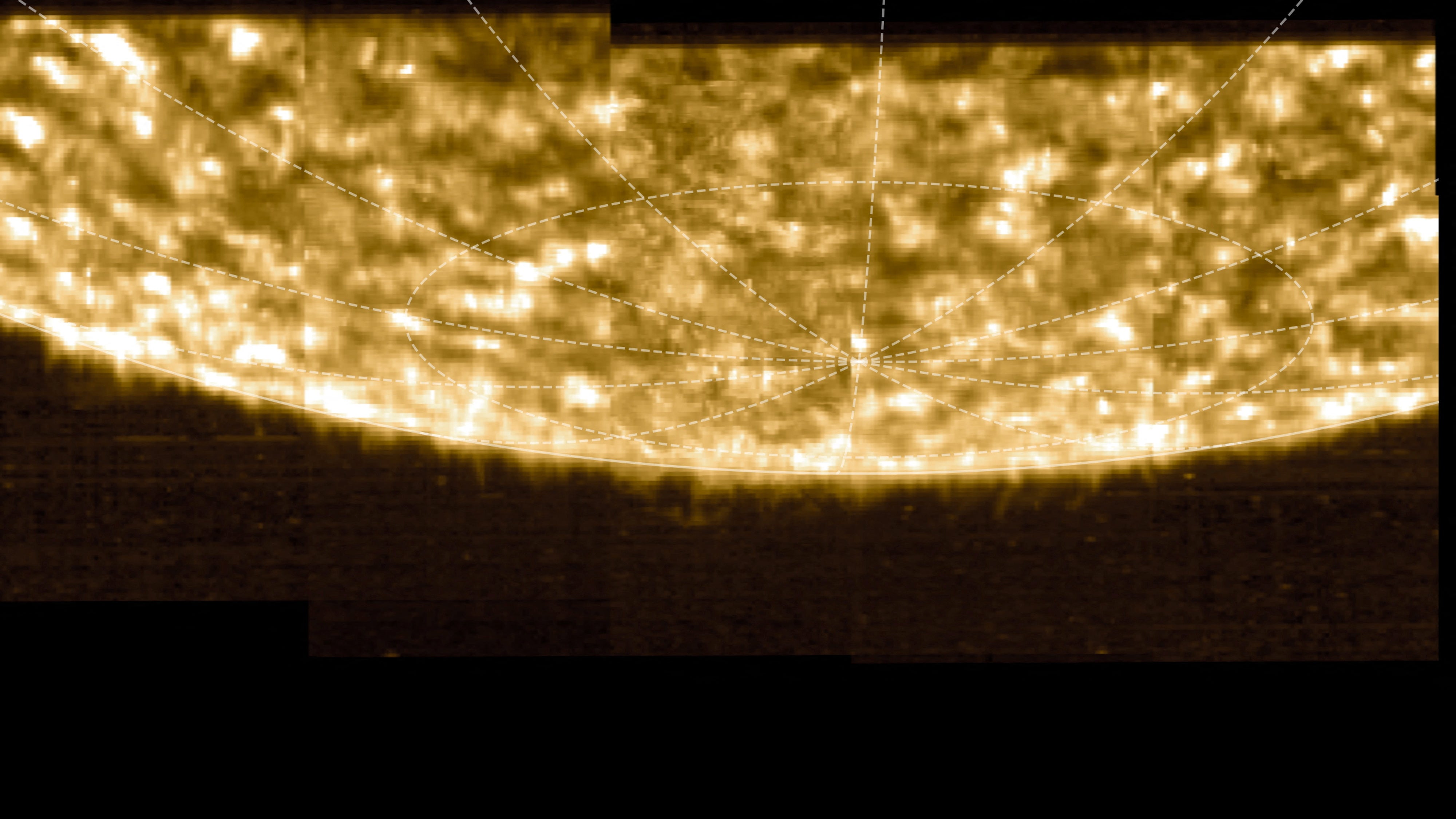

The first-ever images of the sun’s south pole have been captured by the robotic Solar Orbiter spacecraft.

The European Space Agency (ESA) released images on Wednesday using three of Solar Orbiter's onboard instruments.

The images, taken in March, show the sun's south pole from a distance of roughly 40 million miles, obtained at a period of maximum solar activity.

Images of the north pole are still being transmitted by the spacecraft back to Earth.

Solar Orbiter, developed by ESA in collaboration with the US space agency NASA, was launched in 2020 from Florida.

Until now, all the views of the sun have come from the same vantage point – looking face-on toward its equator from the plane on which Earth and most of the solar system's other planets orbit, called the ecliptic plane.

But in February, Solar Orbiter used a gravity-assist flyby around Venus to tilt its trajectory, enabling a view of the sun from about 17 degrees below the equator.

Future Venus flybys will increase that angle to more than 30 degrees, allowing for even better polar observations.

"The best is still to come. What we have seen is just a first quick peek," said solar physicist Sami Solanki from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Germany, who leads the science team behind the spacecraft’s Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager.

Mr Solanki explained that "the spacecraft observed both poles, first the south pole, then the north pole”. He added: "The north pole's data will arrive in the coming weeks or months."

Solar Orbiter is currently collecting information on several solar phenomena, including the sun’s magnetic field, its activity cycle, and the solar wind – a constant, high-speed stream of charged particles that flows outward from the sun’s outer atmosphere and fills the solar system.

"We are not sure what we will find, and it is likely we will see things that we didn't know about before," solar physicist Hamish Reid of UCL's Mullard Space Science Laboratory said.

The sun is a ball of hot electrically charged gas that, as it moves, generates a powerful magnetic field, which flips from south to north and back again every 11 years in what is called the solar cycle.

The magnetic field drives the formation of sunspots, cooler regions on the solar surface that appear as dark blotches. At the cycle's beginning, the sun has fewer sunspots. Their number increases as the cycle progresses, before starting all over again.

"What we have been missing to really understand this (solar cycle) is what is actually happening at the top and bottom of the sun," Mr Reid said.

The sun's diameter is about 865,000 miles – more than 100 times wider than Earth.

"Whilst the Earth has a clear north and south pole, the Solar Orbiter measurements show both north and south polarity magnetic fields are currently present at the south pole of the sun. This happens during the maximum in activity of the solar cycle, when the sun's magnetic field is about to flip. In the coming years, the sun will reach solar minimum, and we expect to see a more orderly magnetic field around the poles of the sun," Mr Reid said.

"We see in the images and movies of the polar regions that the sun's magnetic field is chaotic at the poles at the (current) phase of the solar cycle - high solar activity, cycle maximum," Mr Solanki said.

The sun is located about 93 million miles from our planet.

"The data that Solar Orbiter obtains during the coming years will help modellers in predicting the solar cycle. This is important for us on Earth because the sun's activity causes solar flares and coronal mass ejections which can result in radio communication blackouts, destabilize our power grids, but also drive the sensational auroras," Mr Reid said.

"Solar Orbiter's new vantage point out of the ecliptic will also allow us to get a better picture of how the solar wind expands to form the heliosphere, a vast bubble around the sun and its planets," he added.

A previous spacecraft, Ulysses, flew over the solar poles in the 1990s.

"Ulysses, however, was blind in the sense that it did not carry any optical instruments - telescopes or cameras - and hence could only sense the solar wind passing the spacecraft directly, but could not image the sun," Mr Solanki said.

Scientists find the most intense explosion ever seen in the universe

NASA shuts down X accounts as fears swirl about massive cuts to science initiatives

Odds of ‘city killer’ asteroid 2024 YR4 striking Moon increase

When the ‘Strawberry Moon’ will rise and how to see it

Why Trump and Musk’s spectacular feud could be a disaster for space travel

These mysterious dark ‘streaks’ on Mars aren’t what scientists initially believed