I recently had the occasion to rewatch (OK, for like the 20th time, maybe) the 1976 film Taxi Driver, as research for an essay whose ostensible purpose was to commend the now nearly 40-year-old movie to a younger generation of motion picture enthusiasts. Looking at the movie’s colour-saturated images of a squalid Manhattan hellscape, a slight irony struck me: this place in this time is the subject of more than a handful of rather fond if not outright adoring memoirs that have been popping up over the past five years. Patti Smith’s Just Kids, Edmund White’s City Boy, James Wolcott’s Lucking Out, and, to a lesser extent, Robert Christgau’s Going Into the City. Kim Gordon’s Girl in a Band. Oh, and Richard Goldstein’s Another Little Piece of my Heart. All commemorate The Good Old Days of Bad Old New York. So, too, does Smash Cut: A Memoir of Howard & Art & The 70s & The 80s, by Brad Gooch. Although very early on, Gooch insists: “I’m not nostalgic […] just shocked” at the differences between New York then and now.

Nostalgia is generally frowned upon by avatars of philosophical and intellectual refinement, and not without reason; living in the past is not a productive mode. By the same token, almost all great art is to some extent about loss, about people and places one has survived to give testimony about. If you’re going to go there – the past, that is – you might as well own it. Gooch, a fiction writer and poet who’s also penned useful biographies of Frank O’Hara and Flannery O’Connor, here testifies on his formative years as a writer, his long love affair with Howard Brookner, the film-maker (the most acclaimed work of his too-short career was Burroughs, a revealing documentary about the notorious groundbreaking author and all-around bad example William S Burroughs), and the experience of being a gay man in New York both immediately before and during the plague years of HIV/Aids.

Gooch’s story is compelling, his telling it not always so. The first half of Smash Cut is clunky, rattling; Gooch’s voice is very unsure of itself. Patti Smith’s assured, affectionate prose makes her romanticising of her past not merely palatable but delightful; White’s dry critical detachment is consistently bracing; Christgau’s Real-New-Yawka frankness and intellectual knottiness gooses the reader in unexpected places. Gooch doesn’t muster anything nearly as impressive, at least not at first. The writer sometimes seeks an avuncular mode, as if addressing young would-be creative types peering in from outside the limits of a city Smith now advises the early 21st century’s generation of just-kids to stay away from: the place is just too expensive.

Naturally Gooch wants to play hip uncle, and who wouldn’t, but he’s more accurate at noting the home furnishing eccentricities of various East and West Village down-at-the-heels apartment dwellers (“he clicked on a metal light clipped to grey industrial shelves near the door”) than he is at cultural history. Writing on one of his first dates with Brookner, Gooch remembers going to see a band fronted by a friend of Howard’s, and notes: “Punk in its beginnings included lots of quick suburban high-school echoes …” While one hesitates to take on the role of That Old Punk Guy, Gooch is here writing of May 1978, by which time the Sex Pistols had played their last show and imploded, the Ramones had three LPs out, and Brian Eno was recording the post-punk noise rock No New York anthology over in SoHo. The beginnings of punk were already long past, by New York standards at least.

There’s also a frustrating sketchiness at work here. Gooch, with his secular Wasp background, seems a slightly unusual candidate to have a Episcopalian nun as his therapist. When he describes his passages through the anything-went atmospheres of the pre-Aids sex clubs of the late 70s, he implies that a kind of self-mortification was key to the pleasure of his times there. But he never goes too deep or gets his authorial hands too dirty. The resultant effect doesn’t strike one as evasive so much as dully ingenuous.

While Gooch steers clear of self-aggrandisement, he’s not particularly seductive. His lack of an inspired gossip’s killer instinct speaks reasonably well of him as a person, but makes for awkward reading. Describing the first New York Film Festival screening of Burroughs, Gooch writes: “I remember James Grauerholz sitting in front of us, and watching the back of his neck for blushing, as there were moments when he made some uncomfortably damning remarks about how he was the son William had wanted instead of his actual son, Billy, an awkward comment.” Verbal clams notwithstanding (“uncomfortably damning” is not in itself an indefensible phrase, but left hanging there by itself, it clangs dopily), the ultimate effect of the sentence is an exasperated “Well?” since Gooch never does describe Grauerholz’s reaction, neck-based or otherwise.

Relatively late in the book, there’s a swift, exceptionally smart description of the different work dynamic that Brookner adopted with Burroughs, contrasted with that of a new film subject, the considerably more buttoned-down theatre director Robert Wilson. This newfound deftness closed the case for me: Gooch, I concluded, is not particularly at ease, let alone confident, when writing about himself. This can be a pretty pickle for a memoirist, obviously.

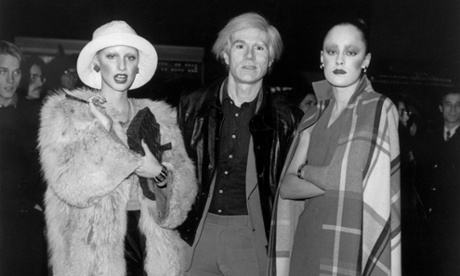

Then again, it might just be a matter of what version of himself he’s writing about. Smash Cut picks up steam at very particular junctures: his quick sketches of Andy Warhol and Robert Mapplethorpe (a central figure, of course, in Smith’s book; he also makes a memorable cameo near the end of White’s chronicle) are great, his portrait of his alliance with Brookner undergoing the crucible of separately taking-off careers (while living at the fabled Chelsea hotel, yet) is multifaceted and involving.

But the book really catches fire in its final section, an account of Brookner’s illness and death. A section in which Gooch excoriates himself for a lack of “bravery” when dealing with Aids victims who weren’t the love of his life is terribly painful. His story of a near seduction by “Sean”, a latter-day boyfriend of Brookner’s, with whom Gooch conducts a disarming flirtation in between visits to Brookner in the hospital, is similarly vivid. Finding these valuable bits near the end of a relatively brief book, I was both moved and a little ticked off. More such passages would have made Smash Cut more of a pleasure to read.