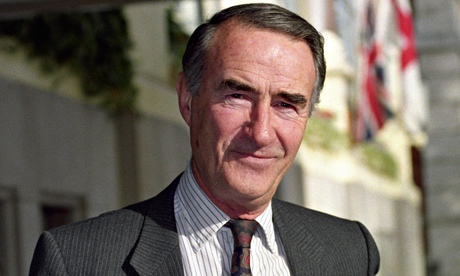

Few successful businessmen have made a mark at the heart of British politics. Skills that work in business are not easily transplanted to Whitehall or Westminster. Yet Sir John Hoskyns, who has died aged 87, had a major impact as the first head of Margaret Thatcher’s policy unit in 10 Downing Street between 1979 and 1982. Thatcher became ambivalent about him, yet was unhappy to see him depart. He was perhaps too endowed with some of her qualities, notably single-mindedness, courage, drive and clarity – and perhaps too radical. After Downing Street, he resumed a successful career in business.

The army did much to shape him. He was born in Farnborough, Hampshire, son of Lt-Col Chandos Hoskyns and his wife Joyce (nee Taylor). His father was killed in 1940, commanding a Green Jacket battalion defending Calais, when Hoskyns was 12. After Winchester College, he entered the army in 1945 and rose to be captain in the Rifle Brigade. The army reinforced his sense of discipline and self-confidence. He had a knack with computers and joined IBM in 1957, leaving in 1964 to start his own computer company. This later became the successful Hoskyns Group, of which he was chairman and managing director. He sold out for a large sum in 1975 and was then able to devote himself to public affairs.

Like a number of businessmen Hoskyns was disillusioned with the corporatism of the time, and despaired of the politics as usual which ignored what he regarded as the real problems. He was a radical who would not find a home in any party and gravitated to dissenting Conservatives. He impressed Alfred Sherman, who had helped to set up the Centre for Policy Studies in 1974 as a thinktank for Keith Joseph and Thatcher. Sherman introduced Hoskyns to Joseph and then to Thatcher. The CPS brought together people such as David Young, Alan Walters, Sherman and Norman Strauss – who all supplied some of the fire power for early Thatcherism.

At the CPS, Hoskyns and Strauss developed the Stepping Stones programme, drawn up in great secrecy. This was an incremental approach to try and reverse Britain’s economic decline. Bringing the unions to heel was seen as the first step to correct the deteriorating public finances, declining economic competitiveness, over-manned public sector and double-digit inflation.

The approach was politically explosive in 1977 and 1978, when some Conservatives were trying to reach an accommodation with the unions. The programme also went against the Labour government’s vaunted social contract. Hoskyns was supported by Joseph and Thatcher but opposed by many in the shadow cabinet. The approach won acceptance only in early 1979, following the winter of discontent. Hoskyns joined Thatcher’s private office; she appreciated his practical businessman’s approach to problems, and his optimism that something could be done.

In January 1979, Thatcher clearly had him in mind for a job in No 10. She suggested he talk to Lord (Victor) Rothschild about work in Whitehall. Rothschild, the first head of the Central Policy Review Staff, set up by Edward Heath, warned that the mandarins would try to stifle. Hoskyns was already suspicious of the civil service. When Thatcher offered him the policy unit, his first words were: “I’m not here for the beer. When I’m finished I’ll go.” He wrote out his own terms of reference and she accepted them. He had ready access to her and made a point of speaking truth to power. He was not a comforter or courtier and Thatcher until late in the day accepted this. An exchange with the prime minister’s parliamentary private secretary, Ian Gow, who tried to protect Thatcher from visitors, was typical. “Our girl is tired,” said Gow, trying to stop an approach from Hoskyns. “I’m tired too. It goes with the bloody job. I’m going in,” replied Hoskyns.

His policy unit concentrated on strategy and was obsessive about the key problems – excessive public spending, inflation and trade union power. He, rather than Thatcher, set the tasks for the unit. He dismissed suggestions that he think about ways of giving concessionary TV licence to pensioners as “a second-order problem”.

He and the policy unit had a major influence on Geoffrey Howe’s 1981 budget; together with Walters he urged fiscal tightening on a reluctant Treasury. He was a persistent advocate of tough legislation on the unions and welcomed the replacement of James Prior by Norman Tebbit as employment minister. He successfully argued for curbing the indexing of benefits and pay comparability for civil servants.

There were collisions, particularly with the powerful Robert Armstrong, the cabinet secretary. A request to expand his small unit and bring in John Redwood to work on privatisation was turned down. He hated speech writing and Thatcher’s habit of working with a large team. She reacted with cold fury to his memo criticising her leadership style and suggestion that she build up cabinet colleagues and not snipe at them. By the end of the 1981 he felt that he could not do much more, although much remained to be done, particularly on welfare reform, and that he and the prime minister were irritating each other.

Joseph, acting on her behalf, urged him to stay and offered him the leadership of a combined CPRS and policy unit. Hoskyns, prompted by Sherman, spelled out his demands. He wanted to politicise the CPRS with his own people, report directly to the prime minister, not the cabinet secretary, and embark on a Stepping Stones Two. His proposal was turned down on the grounds that the CPRS was a non-political body. Hoskyns detected the hand of Armstrong again. Although Thatcher offered an expanded policy unit, it was not enough and he left. He was knighted later that year.

Hoskyns then attacked the senior civil service for being defeatist and racked by 40 years of decline. Its reliance on traditional ways and political impartiality meant that it was a barrier against innovation and commitment to radical policies. He wanted to end the tenure of top civil servants and allow prime ministers to appoint their own people. He was dismissive of many politicians. “Their so-called political experience is overrated. They have no experience of managing anything and their idea of action is to make a speech.”

As director general of the Institute of Directors, 1984-89, he expressed trenchant views on current politics. In 1990 he became chairman of the Burton Group. He joined old Thatcherite allies in campaigning against the single European currency.

Hoskyns was irreverent and direct, and his charm and exquisite manners combined with occasional shop-floor epithets. His belief in clear and strategic thinking could make him demanding company when he was serious. He admired the military and was a good shot, and one of his clubs was the Green Jackets. He liked to tell the story of meeting an old army chum after a gap of 20 years and, on being asked what he was doing, replied that he now worked for Thatcher. “You must be a shit,” was the retort.

He is survived by his wife, Miranda (nee Mott), whom he married in 1956, and their two sons, Ben and Barney, and daughter, Tam.

• John Austin Hungerford Leigh Hoskyns, businessman and policy adviser, born 23 August 1927; died 20 October 2014

• This article was amended on 3 November 2014. Because of an editing error, Ian Gow was referred to in the original as Margaret Thatcher’s personal private secretary, rather than her parliamentary private secretary. This has been corrected.