After the end of World War II, 575,000 Japanese were forced to work in the former Soviet Union and Mongolia. Known as Siberian detainees, it is estimated that about 55,000 of them died in frigid cold from starvation and hard labor.

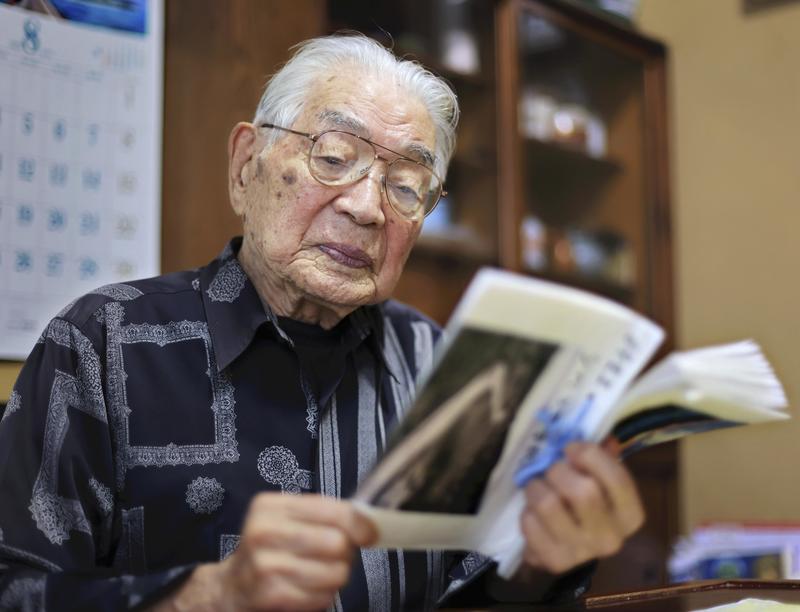

Yuisuke Tanaka, a 94-year-old musician, is one of the former detainees who to this day continues to talk about his memories.

"Being alive was worse than being dead," Tanaka said while playing the accordion.

Tanaka was recruited into the war and was situated in Manchuria, now northeastern China, when it ended.

He was detained for about four years in Kazakhstan, which was at that time part of the former Soviet Union.

In addition to partially losing two fingers to frostbite, he suffered a head injury under harsh working conditions.

To convey his detention experiences, Tanaka has been holding events throughout Japan where he gives a mixture of talks and accordion performances.

On a recent summer day, Tanaka held such an event at a temple in Takasago, Hyogo Prefecture. About 60 people gathered in the main hall to watch the 94-year-old's two-hour performance, which was physically taxing.

"I'll never retire," Tanaka said. "As a survivor I'll continue to pass down the tragedies of detention until the day I die."

Masanori Araki, 96, was also a detainee in the former Soviet Union who returned to Japan after experiencing many accidents and illnesses that left him hovering between life and death while many of his compatriots perished.

He kept his tales of detention under wraps for many years, but increasingly felt that he "could not bear the thought of this tragedy being forgotten as if it had never happened."

After retirement, Araki began giving lectures about the detentions and up until the age of 92 he participated in a group that collects remains of the war dead.

He continues to speak at local workshops and at elementary and junior high schools about the tragic experiences he faced as a detainee.

"Some of my fellows have neither remains nor belongings," Araki said. "They are remembered only by those who survived."

Maizuru, Kyoto Prefecture, served as a base for internees returning to Japan.

Mutsumi Nagamine, a 43-year-old curator at the Maizuru Repatriation Memorial Museum, said: "As the number of people who actually experienced the war is decreasing, the question is how to pass on the memory of the war to younger generations. In order to prevent the tragedy from fading, we'll work to communicate to younger generations the facts about detention."

Read more from The Japan News at https://japannews.yomiuri.co.jp/