June 14 marked five years since the Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry suspended proactive recommendations for inoculation with human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines (see below) aimed at preventing cervical cancer. The suspension was the result of complaints of severe adverse effects, including body pain and movement dysfunction, by women subsequent to being vaccinated. These women have gone on to file lawsuits claiming drug-induced suffering. Meanwhile, vaccination rates have dropped to below 1 percent even though HPV vaccinations are classified as routine vaccinations. What is the current situation and what are the issues involved? Three experts holding different viewpoints -- an obstetrician and gynecologist with expertise in cervical cancer screenings, a lawyer supporting the legal action, and the Japan representative of a research organization that assessed the efficacy of the vaccines -- spoke with The Yomiuri Shimbun about the issue. The following are excerpts from the interviews.

(From The Yomiuri Shimbun, June 15, 2018)

Govt measures to aid victims are inadequate

Five years have passed since the Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry suspended proactive recommendations for the HPV vaccination, yet there has been no effective treatment or cure for women suffering from a variety of adverse effects.

Many of the victims were vaccinated while they were in junior high school and have been suffering from adverse symptoms such as pain all over their bodies, cramping, visual disorders, severe fatigue and memory problems developing one after another.

Many of the girls were forced to change the course of their lives. It became difficult for them to attend school; they dropped out and abandoned their hopes of going on to higher education. On top of this, a big problem now is the barriers that people over 20 are experiencing in trying to find a job. Even those who were able to receive consideration at school are finding it hard to secure employment. Both they and their families feel very uneasy about the future.

In 2016, lawsuits were filed against the government and pharmaceutical companies to seek damages. Cases are currently pending in four district courts, including Tokyo and Osaka, with 123 plaintiffs.

In the lawsuits, the plaintiffs are seeking permanent remedial measures on the premise of the legal responsibility of the government and pharmaceutical companies, together with the preventative measures.

Some people have received benefits from the government's relief system, but this basically covers the reimbursement of the cost of medical expenses that have already been paid. There are many people who will not be eligible for benefits such as a pension.

A fundamental treatment to cure the conditions victims are suffering has yet to be found, and there are only a limited number of medical institutions where victims can feel confident to receive treatment. For this reason, many victims have to travel long distances to receive treatment. Adequate remedial measures have most definitely not been taken.

A causal relationship between the vaccination and the various adverse conditions has not been proved scientifically. However, in addition to knowing the risks of the vaccine components, there is a lot of research that clarifies the characteristics of the adverse conditions, together with the data that emerged from different kinds of examinations. I believe that the dangers of the vaccination are well shown. Viewed in the light of past cases of drug-induced damage to health, this kind of information should not be disregarded.

To begin with, the proven preventive effects of these vaccines only extend as far as "precancerous lesions" of cervical cancer. It has not been proven that they can actually prevent the cancer. The vaccine only covers preventing certain types of HPV, and their preventive effect only lasts for a limited time. Particularly high levels of efficacy and safety are required for the government to designate HPV vaccines a part of routine vaccinations, which people are obliged to make efforts to get. When there are health examinations as a measure against the cancer, it is not rational to make routine use of vaccines whose effectiveness is limited, exposing otherwise healthy women to such risks.

Victims suffering from postvaccination adverse conditions are not limited to those in Japan. In April, associations calling attention to the harm caused by the vaccinations in five countries -- Japan, Britain, Colombia, Ireland and Spain -- released a joint statement. They are seeking the development of treatments and support for the daily lives of victims and people concerned.

The current Japanese HPV vaccination rate is less than 1 percent, with almost no new victims. However, should proactive recommendations for the vaccines resume, people will once again experience the same kind of suffering. What is being sought is not the resumption of recommendations but the removal of HPV vaccines from routine vaccinations.

-- This interview was conducted by Yomiuri Shimbun Staff Writer Tomoko Koizumi.

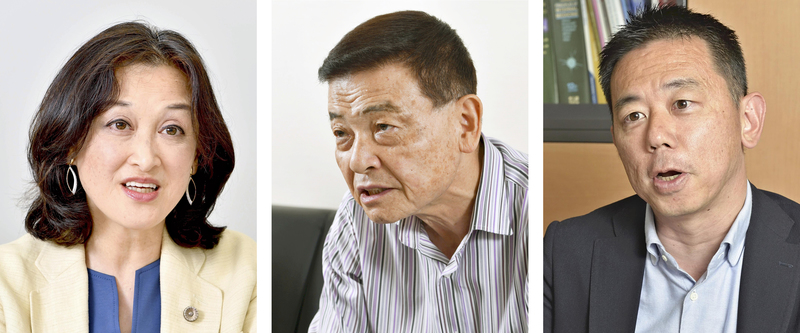

-- Masumi Minaguchi / Cochair of Attorneys for Nationwide Lawsuits for HPV Vaccination Victims

Minaguchi, 59, is a lawyer and secretary general of Yakugai Ombudsperson Medwatcher Japan. She was a member of the Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry's committee for the examination of drug-induced hepatitis and prevention of its recurrence.

Thinking that screenings are enough is a mistake

I have practiced as an obstetrician and gynecologist for more than 40 years, specializing in the treatment and research of cancer in women, and have performed 30 to 40 surgeries for cervical cancer each year. A major characteristic of cervical cancer is the fact that we know the cause to be human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. The person who discovered this received the 2008 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Vaccines that can prevent infection with this virus have the potential to reduce the number of women who suffer from this kind of cancer to zero in the future. I felt this to be really good news.

When I was young, many of the patients were in their 50s or older. Even if they had to have their uterus removed, they were happy to be still alive.

The number of young patients has increased recently, however. We do not have a detailed picture of the causes, although there are some indications that it may be caused by the earlier commencement of sexual intercourse. Even in cases of early detection, removal of the uterus is basically unavoidable. The woman will not be able to bear children, which will have a major impact on her later in life.

I cannot forget a woman in her early 30s on whom I performed surgery about five years ago. She was in her 20th week of pregnancy, and the cancer was more than 4 centimeters in size. When cervical cancer is discovered in a pregnant woman, the attending physician makes a decision based on various considerations, such as the degree to which the cancer has progressed, the feelings of the patient, and the life of the fetus. Delaying surgery would have put this patient's life at risk, and so I had to remove the uterus with the fetus still inside. It was a truly heartbreaking experience.

While women are developing cervical cancer at a younger age than in the past, they are now giving birth at a later age due to factors such as later marriage. These two peaks have come to overlap exactly when women are in their mid 30s. As a result, we also have many sad cases of women discovering that they have cancer during their prenatal checkups.

While the opinion that "performing cervical cancer screenings is enough, and there is no need for a vaccine" does exist, it is a mistaken viewpoint.

At best, about 70 percent of abnormalities, including precancerous lesions -- which are a potential precursor to cancer -- are picked up in a screening, while 30 percent of abnormalities are missed. And the truth is that fewer than 30 percent of women in their 20s are setting these important screenings.

Also, even if abnormalities are detected at the precancerous lesion stage, cutting the entrance to the uterus triples the risk of a premature birth. It is best to get rid of not only cancers but also precancerous lesions wherever possible.

In other words, cervical cancer can be prevented when we have both vaccines and screenings. The government should resume proactive recommendations for the HPV vaccine as soon as possible.

The current vaccination rate is close to zero, however. It will take quite some time to restore this to 70 percent or 80 percent as it was in the past, even if recommendations are resumed right now.

This makes me want to concentrate on getting the message about the need for this vaccine out to both the young women who would be getting vaccinated, and also to legal guardians and educators. I would like to do my utmost to popularize a method that combines vaccinations with examinations (HPV tests) that check to see whether one has been infected with HPV already -- in other words, a second protective shield -- and to achieve higher examination rates.

-- This interview was conducted by Yomiuri Shimbun Staff Writer Yohei Takei.

-- Mitsuaki Suzuki / Head of Cancer Center at Shin-Yurigaoka General Hospital

Graduated from Keio University School of Medicine in 1974. Suzuki took up his current position in 2015, having held posts such as professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Jichi Medical University. He is also currently executive director at the Japan Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and an executive committee member on a council of experts targeting the elimination of cervical cancer. He is 68.

Shift from routine to voluntary vaccinations

Cochrane is an international organization headquartered in Britain that analyzes a range of clinical research with the aim of disseminating medical findings based on scientific evidence.

In May, we published a report that evaluated 26 clinical studies conducted in countries worldwide on HPV vaccines. According to the report, there is strong evidence of the vaccines' effectiveness in preventing precancerous lesions. Because these precancerous lesions generally go on to develop into cancer, this can be said to strongly suggest the vaccine's effectiveness in preventing cancer as well.

Though these clinical studies do not give much indication of the frequency of side effects, it appears to be rather low. However, just because the frequency is low does not mean the women who are suffering from adverse symptoms after being vaccinated can be forgotten. For them, this suffering is a 100 percent certainty. Vaccinating healthy people is a means to prevent a disease that might occur in the future, so the shock is that much greater.

However, I would also like to make the point here that the overall vaccine policy should not be influenced by the risk of infrequent side effects.

The government's current policy, which describes HPV vaccinations as routine vaccinations but refrains from actively recommending them, is like having a foot on the accelerator and the brake at the same time. This sends a contradictory message to the public and causes confusion.

What I would like to propose is first making the HPV vaccination voluntary, administered at the individual's request and paid for out of their own pocket, and then for the government to resume a policy of recommending the vaccination. I feel now is the time for us to slowly press our foot on the gas pedal.

Many of the diseases that routine vaccinations aim to prevent, including measles and rubella, are highly infectious, and there is a strong implication that the purpose of these vaccinations is to protect large groups of people from infection. However, given that HPV is transmitted through sexual intercourse and that the ultimate aim of the vaccination is to prevent cancer, the HPV vaccination is qualitatively different from other vaccinations.

However, at about 50,000 yen for a total of three vaccinations, it is extremely expensive. If it becomes a voluntary vaccination paid in full by the individual, criticism will emerge that economic disparities will lead to health disparities. So this vaccination should be covered by public subsidies, with just a small amount left to be covered by the individual. Having the individual pay for part of the vaccination creates a kind of choice, in the sense that the individual has made their own decision to receive the vaccination.

In addition, a no-fault compensation program should be created for cases when something does occur after receiving the vaccination. This would allow a victim to be compensated if certain conditions are met, and spare them the trouble of pursuing questions of responsibility and cause-and-effect.

Furthermore, a database must be built to connect the patient's vaccination history with medical records at medical institutions. Scrambling around at the eleventh hour to investigate when something has happened does not deliver good results, relative to the amount of money and labor spent.

There are many hurdles to clear, including the Protection of Personal Information Law, but once a database is created, a vaccine policy based on scientific evidence can be adopted.

-- This interview was conducted by Yomiuri Shimbun Staff Writer Yohei Takei.

-- Rintaro Mori / Representative of Cochrane Japan, Head of Department of Health Policy at National Center for Child Health and Development

Mori, 47, graduated from medical school at Okayama University in 1995. He has worked as a pediatrician in Australia and Japan and been involved in drafting health care policy in Britain. He went on to positions including technical officer at the World Health Organization and associate professor at the University of Tokyo. He took up his current position in 2014.

-- HPV vaccines

Cervical cancer is caused by infection with the human papilloma virus (HPV), which is spread through sexual intercourse. About 10,000 people develop this kind of cancer in Japan each year, with about 2,700 cases resulting in death. While HPV vaccines will prevent HPV infection, they are not effective if administered post-infection. Two vaccines have been approved, Cervarix and Gardasil. In November 2010, the government started subsidizing vaccination costs. In April 2013, HPV vaccination became part of routine vaccinations, but after a quick succession of reports of suspected side effects, the government suspended proactive recommendations on June 14 of the same year. Routine vaccinations in a series of three doses are given to girls between the sixth grade of elementary school and the first year of high school. About 3.4 million people have been vaccinated thus far, with reports of suspected negative side effects from about 3,000 people.

Read more from The Japan News at https://japannews.yomiuri.co.jp/