In She’s Gotta Have It, Nola Darling is a figurative painter, living in Brooklyn; 31 years ago, when Spike Lee created her for the film that splashed his vision, vividly and indelibly, all over Hollywood, she was a graphic artist.

So, sure, there have been tweaks to her CV for this Netflix remake, not least because there are now 10 episodes; box sets can make films seem as fleeting as adverts, events that only remind you of the story. But the premise – the bit that made it arresting and sexy, combustible, stinging and talked-about – remains unchanged: Darling is sleeping with three men, a stable and mature one (Jamie Overstreet), a narcissistic and shallow one (Greer Childs), and an eccentric and playful one (Mars Blackmon). She’s not doing it for cutesy, Shakespearean reasons; she’s not trying to make her mind up, or refereeing a battle between her head and heart. She’s doing it because she’s “sex positive, polyamorous, pansexual”.

“I consider myself abnormal,” she says, in a direct-to-camera monologue that takes a bit of getting used to, “but who wants to be like anybody else?” But why this kind of abnormal, the world around her asks. Doesn’t she ever feel like “giving [her] coochie a rest?” (from her best friend). Is she a sex addict? (from Childs).

Contexts change, contexts remain the same: “She is a woman who is juggling three men, and I think there are more women like that now,” Lee said in an interview with feminist scholar Salamishah Tillet, “but the way those women are judged hasn’t necessarily changed as far as men go.”

It would be a kiss of death to call this an “issues-based dramedy”, but it is a drama, it is comic, and it does have issues. When female desire is acknowledged as a force in its own right, which it almost never is, why is that still so threatening? Why is it pathologised and what does that do to female autonomy? Alongside that, before “intersectionality” had been coined (though not long before), the original film had this driving curiosity: what happens if you take the gender who aren’t allowed erotic agency (women) , and the race who aren’t allowed sexual expression (people of colour) , and you unite those in one lascivious character?

“How often,” Lee asked in 1986, “have you seen a black man and woman kiss on the screen?” The question is quietly devastating; the decades haven’t resolved it. Rather, other flashpoints have emerged, and this remake fillets in the gentrification of Brooklyn, the Black Lives Matter movement, economic and political iterations of racism that were, culturally if not literally, a lot more ignorable last century.

When the film came out, the feminist critique was distilled by bell hooks, who asked whether Darling really did embody bold, self-confident female desire, or something else entirely: part way through, Jamie rapes her, an old-school 70s screen rape, where she starts off saying “no” and ends up enjoying it. Was it really rape, considering they’d had sex before, and she’d met him in order to have sex, and she only said no at the beginning? Debates were had in newspapers then that would now only come up in golf clubs. The New York Times concluded that “his violence seems natural and does not diminish interest in or sympathy with the character”.

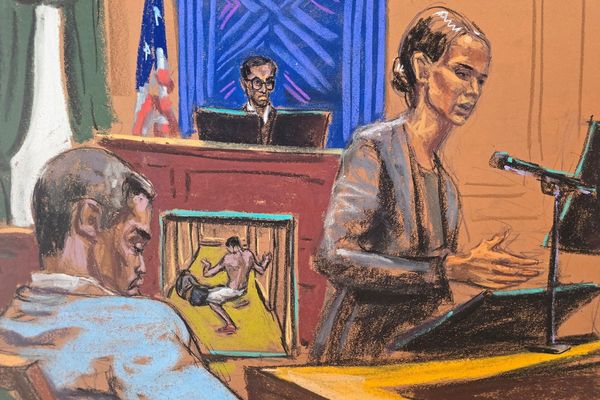

So you cannot say there has been no progress. Lee said 10 years ago, in an interview with NPR, that he regretted the scene; asked why he didn’t just go back and cut it out, he said: “You gonna go back to Gone With the Wind and cut out the Mammie stuff? It’s done.” In this series, Darling isn’t raped by any of her lovers, but rather, is grabbed in the street by a stranger – the fly-posted art she then does in response is vandalised. This feels painfully current and much more challenging than any ‘is-it-isn’t-it?’ conversation about a rape. These violations colour everything, the way Darling relates to men, to women, to intimates, to strangers, to her work, to her parents, in a way that’s vividly relatable. Yet I was also biting back the collective urge of the un-woke sisterhood, to minimise: come on, Nola, some guy just grabbed your wrist; some other guy just sprayed “cunt” all over your posters; the world didn’t end.

That has been the most interesting question, post-Trump, post-Weinstein: not why men protect themselves. nor why men protect each other; not why women don’t speak out, nor even why women don’t defend one another; but that germ of hostility for the woman who thinks she shouldn’t be accosted, molested, harassed. What makes her so special? Past the harassment, in Darling’s behaviour and its counterpoints in her friends, these questions persist: how does she get to be so happy in her skin, how come she isn’t saving for an arse-implant, why isn’t she waiting by the phone for a guy, what makes her believe in her art, in herself?

Spike Lee wrote the original Nola Darling himself, and for her descendant, collaborated with four female writers, Radha Blank, Eisa Davis, his sister Joie Lee and the playwright Lynn Nottage. It shows; she sounds more three-dimensional, more realised. She is winningly played by DeWanda Wise. The real work of Hercules is not to make her credible but to make her likable, when she doesn’t seek approval: sometimes it comes off, sometimes it doesn’t. It’s exhilarating when it doesn’t.

She’s Gotta Have It launches on Netflix on Thursday 23 November