The idea of the aristocratic Count Dracula turning up in China and commanding a troupe of supernatural Chinese acolytes trained in kung fu sounds bizarre. But that’s just what happened in 1974’s The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires.

The unlikely film, which was shot entirely in Hong Kong and primarily at Shaw Studios, was a collaboration between Shaw Brothers and Britain’s Hammer Film Productions, well known for lurid horror movies like Dracula and The Curse of Frankenstein during the late 1950s and 1960s.

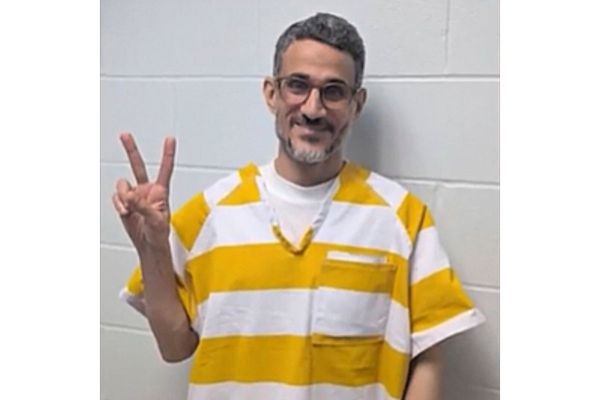

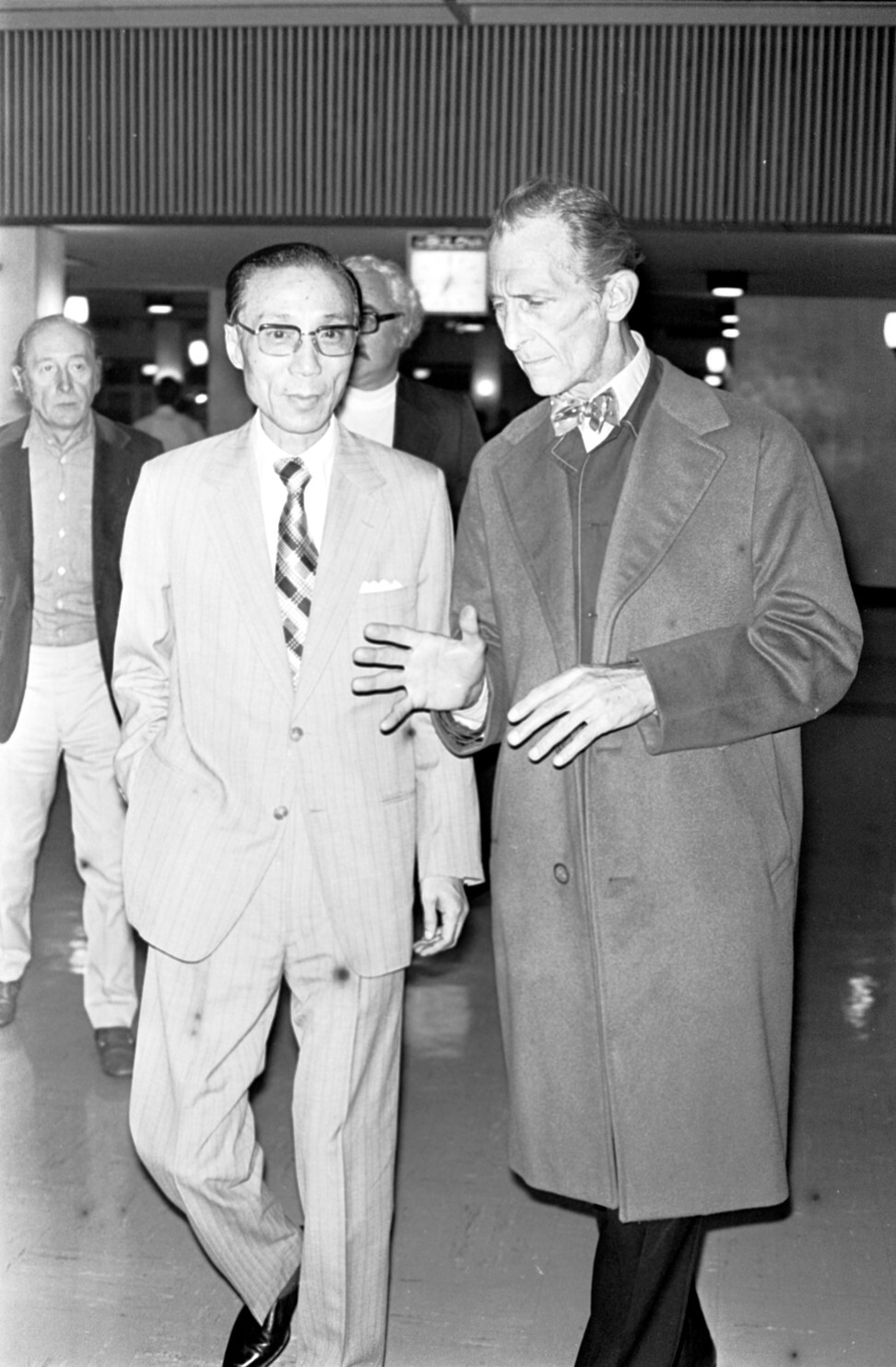

It paired Hammer regular Peter Cushing, as the legendary vampire slayer Professor Van Helsing, with martial arts legend David Chiang Da-wei, who played the leader of a group of Chinese vampire hunters who help him track down the Count in China.

Performers like Shaw Brothers star Shih Sze, Chan Shen, and Lau Kar-wing also featured, although they were given few lines and very little to do outside of the action scenes.

The martial arts scenes, which were choreographed by two regular collaborators with prolific director Chang Cheh, Lau Kar-leung and Tong Kai – perhaps under the supervision of the uncredited Chang himself – are plentiful, and the combination of kung fu and Hammer’s typical Gothic horror stylistics gels better than expected.

Although the film has undeniable kitsch value today, its director, Roy Ward Baker – a Hammer films veteran – was not far off the mark when he described it as “an absolute disaster” in his online memoirs.

The story begins in Transylvania – in reality, a hill in the New Territories – when a Chinese priest (Chan Shen) visits Count Dracula (John Forbes-Robinson) in his tomb and tells him that seven golden-masked vampires await resurrection in a small village in China. Dracula accedes to the priest’s request to go to China, and ungraciously takes over his body.

The film then cuts to “Chungking” (Chongqing) in 1904, where famed vampire hunter Van Helsing (Cushing) is delivering a speech about vampires in a university. Oddly, the audience claim that Chinese people are not superstitious, and walk out – except for Hsi Ching (David Chiang), who tells Cushing that seven golden-masked vampires are terrorising his village.

With the rich heiress (played by Hammer starlet Julie Ege) who’s funding the expedition in tow, Van Helsing and Hsi Ching, along with his brothers and sister, set off for the village to dispense with the vampires.

The story, as Baker points out in his memoirs, does not really add up. This is mainly because the character of Dracula was a late addition to the script, which was an adaptation of an earlier script that neither featured the Count nor a Chinese setting.

When Warner Brothers signed on to distribute the film in the United States, they demanded that Dracula be part of the film, claiming that it would be much easier to market in the US if it featured a known villain. So an appearance by Dracula was quickly added at the beginning and end.

But both companies were disappointed when Christopher Lee, Hammer’s legendary Dracula, turned the project down. Lee was unhappy about his previous two “modernised” Dracula films, Dracula AD 1972 and The Satanic Rites of Dracula, which he felt were ridiculous, and Legend seemed no better. (Interestingly, Lee had previously shot some films at the Shaw Bros studio in Hong Kong in the late 1960s.)

The collaboration came about because of problems at Hammer. The studio, a family business, was losing ground in the early 1970s because its Gothic horrors seemed old-fashioned.

Michael Carreras, who had bought the studio from his father in an acrimonious deal, decided that a new style of vampire film was needed. The studio’s US distributor, Warner Brothers, said that Hammer needed to bring its films in line with the latest trends – and in 1973, “latest trends” meant kung fu.

Carreras contacted Shaw Brothers via the Chinese wife of a Hammer staff member, and a deal was struck. The project advanced quickly, but as Baker notes, few preparations had been made, and this led to problems.

Technical staff (cameramen, sound, etc.) were all from the UK, while crew (make-up, art design, etc.) were from Shaw Brothers. Apart from the art director Johnson Tsao Chuang-sheng, whose sets adhere to the “Hammer look” magnificently, the two teams did not work well together and had difficulty in communicating.

As Bruce Hallenbeck notes in his erudite Blu-ray commentary, bad planning meant that the standing sets on the Shaw Brothers lot had no place in the script, so new sets had to be built from scratch. The script called for a desert, and deserts are in short supply in Hong Kong. Horses had to be hired from the Jockey Club, and the genteel racehorses were not very happy with performing in front of the cameras.

Lau Kar-leung and Tong’s martial arts sequences, which are mainly many-against-many swordfighting scenes like those they choreographed for Chang, are adequately staged but poorly filmed and edited.

This is seemingly the result of a cultural misunderstanding. In Hong Kong, the martial arts directors – a position that does not exist in Western filmmaking – take over the set and the direction for the action scenes, and sometimes even take control of the camera after discussing the scene with the director.

When this was mooted on the set of Legend, Baker thought that the Chinese crew were staging a coup. The result was a fractious deal that meant that the Hong Kong fight team staged the fights while the British team filmed and edited them. Consequently Baker, who was evidently unaware of Hong Kong’s reputation for shooting top-notch martial arts scenes, ended up with some very clumsy-looking fights.

In spite of all the resentment on set, Cushing, who spent much of his spare time communing with his recently deceased wife on The Peak, was loved by all. “He was a wonderful actor,” David Chiang said.

Warner Brothers did not like the film and reneged on their agreement to distribute it in the US, something which contributed heavily to Hammer’s descent into bankruptcy. It was finally released in America in a butchered form as The 7 Brothers Meet Dracula.

In this regular feature series on the best of Hong Kong martial arts cinema, we examine the legacy of classic films, re-evaluate the careers of its greatest stars, and revisit some of the lesser-known aspects of the beloved genre. Read .

Want more articles like this? Follow SCMP Film on Facebook

Did you know that among the world's top five health care markets, China is the only one growing at double digits? Get a comprehensive industry review and insights on Covid-19 induced market shifts with the China Healthcare Report, brought to you by SCMP Research. for our 50% early bird discount now. You will also receive access to 6 closed-door webinars led by China healthcare’s most influential C-suite executives. Offer Valid until August 12th 2020.

From our archive