Increased demand for food due to population growth, together with a reduction in suitable arable land, has made pesticides essential for ensuring food security. They play a key role in both increasing agricultural yields and improving food quality – they are estimated to reduce crop losses caused by pests and diseases by around 30%.

As a result, their use has grown significantly in recent decades. Globally, agricultural pesticide consumption rose from 2.8 million tonnes in 2010 to 3.5 million tonnes in 2022 – an increase of 25% in just 12 years.

According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), pesticides are defined as “any substance or mixture of substances of chemical or biological ingredients intended for repelling, destroying or controlling any pest”. They are generally classified according to the type of organism they control.

The main groups are: insecticides, fungicides, herbicides, nematicides, acaricides, rodenticides and bactericides.

Agricultural pesticide consumption in the European Union (EU) accounts for approximately 13% of the global total. Although more moderate than the global trend, pesticide use in Europe is also on the rise. It went from 402,229 tonnes in 2010 to 449,038 tonnes in 2022, an increase of 12%.

This more modest increase is mainly due to stricter regulations in Europe. In 2023, 444 pesticides were authorised for use in the EU, while 954 were banned or not approved, and 43 were under evaluation.

Environmental and health impacts

Although pesticides have made significant contributions to increasing agricultural production, their misuse and abuse also raise significant environmental and public health concerns.

It is estimated that less than 15% of the pesticides applied actually reach the pest they are targeting. The rest is dispersed into the environment, contaminating the soil, water and air. This poses significant risks to environmental health, including poisoning non-target organisms, loss of biodiversity and the development of resistance in pests.

Pesticide residues can also enter the food chain through the consumption of crops and water, increasing the risk of diseases in humans. These include neurodegenerative, cardiovascular, endocrine, respiratory, renal and reproductive disorders, as well as cancer.

European wheat fields

Wheat is one of the world’s most important grains, and is the main food source for almost half of the world’s population. For this reason, the SoildiverAgro project – which brings together researchers from various European countries and is led by David Fernández Calviño at the University of Vigo – has analysed the presence of 614 pesticides in 188 wheat fields.

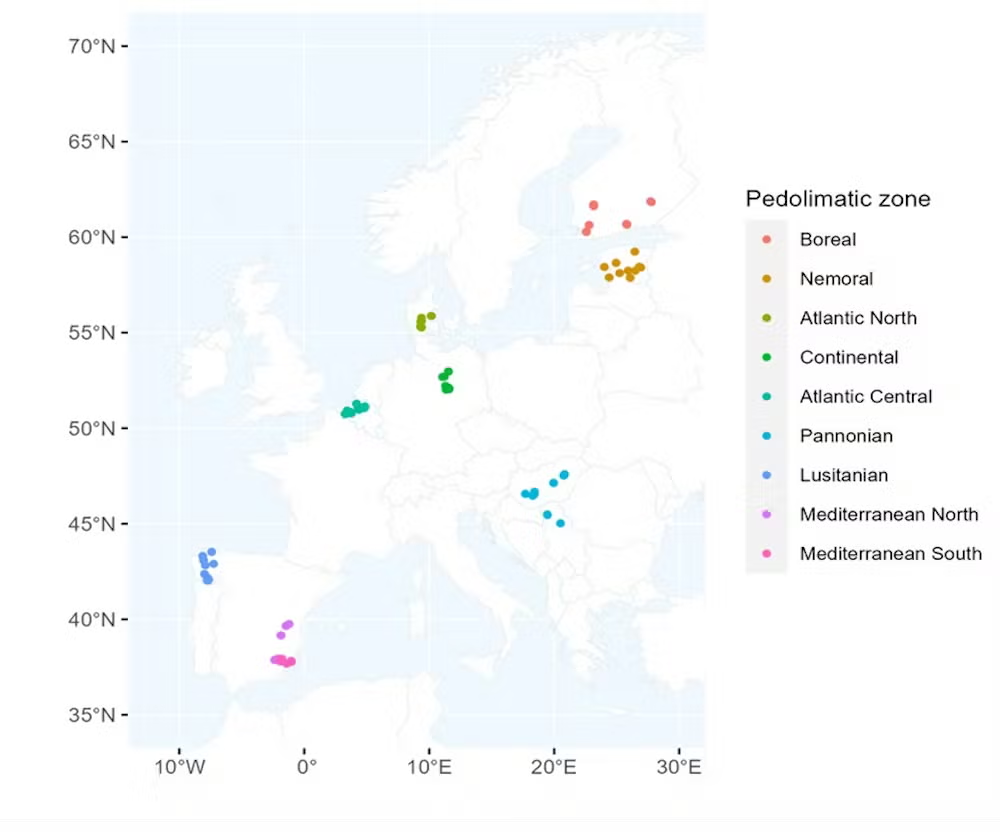

93 of the fields we looked at were conventionally farmed, while 95 were organic. They were distributed across eight countries with a variety of climates and soil types.

Our results are published under an open access licence in the Journal of Hazardous Materials.

99% of conventionally farmed wheat fields had at least one pesticide. In total, 73 different compounds were detected. The most common were fenbutatin oxide (an insecticide) and AMPA (a glyphosate metabolite), which were both present in 44% of samples, followed by the herbicide glyphosate and the fungicide epoxiconazole, present in 39% of samples.

Other frequently detected pesticide residues were boscalid, tebuconazole, bixafen, diflufenican and DDT metabolites, which were detected in more than 20% of the samples.

The results showed notable differences depending on the region of Europe. The continental area (Germany) recorded the highest presence of pesticide residues, both in terms of quantity (average concentration of 0.46 mg/kg) and diversity (average of 13.5 different pesticides per plot). This was followed by the Atlantic area (Denmark and Belgium).

At the opposite end of the spectrum, the Pannonian region (Hungary and Serbia) showed the lowest levels (average of 0.02 mg/kg per field).

Longlasting chemicals

One particularly worrying finding was that pesticide residues were also detected in organic fields. Specifically, 35 different pesticides were found, of which only one (Spinosad) is authorised in organic farming. This indicates that these pesticides persist for years after an agricultural system changed from conventional to organic, as well as the transfer of pesticide residues between different agricultural fields.

About the author

Manuel Conde Cid, Investigador postdoctoral en el área de Edafología y Química Agrícola, Universidade de Vigo, Universidade de Vigo.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Furthermore, 31 of the compounds detected were banned at the time of the study. This confirms the high persistence of certain pesticides – they were still detectable over 40 years after being banned.

We also assessed the ecological threat posed by the different pesticides detected. Those of greatest concern were the fungicides epoxiconazole, boscalid and difenoconazole, and the insecticides imidacloprid and clothianidin. In contrast, herbicides such as glyphosate and its metabolite AMPA were, although ubiquitous, a relatively low ecological risk.

A threat to humans and ecosystems

Our findings show that pesticide residues are widespread in agricultural fields across Europe and around the world. To improve this situation, it is essential to move towards a more sustainable use of these chemicals.

In this regard, replacing highly persistent and toxic compounds with less harmful alternatives – such as bioinsecticides, plant-derived products or beneficial microorganisms – can significantly reduce soil and water contamination, as well as the impact on biodiversity.

Another complementary approach is the promotion of agricultural practices that improve soil health and the natural resistance of crops, such as crop rotation, reduced tillage, the use of cover crops and certified organic farming. These measures not only help reduce the need for pesticides but also facilitate the breakdown and elimination of existing residues in the soil, limiting their transfer to other ecosystems and the food chain.

The combination of strict regulation and the adoption of good agricultural practices, therefore, offers a promising way to minimise the risks of pesticides, without sacrificing agricultural productivity.

Merck’s move to axe £1bn UK expansion was ‘commercial decision’, says minister

THG profits hit by high whey protein costs as trading gains momentum

Trainline shares accelerate on rosier earnings outlook

Merck scraps £1bn London expansion as report warns UK drugs sector ‘losing out’

Ancient burial upends what we know about Stone Age women and children

These spiders have ‘dark DNA’ - and it could change the way we understand evolution