Finding women’s contributions in scientific history can be challenging, and not just because there often weren’t many women working in science. In a post for the Google Blog “The Keyword” last month, Effie Kapsalis, Senior Digital Program Officer at the Smithsonian Institution, shared how the Smithsonian collaborated with Google Arts and Culture to reveal women’s contributions to the museum archives.

A few years ago, the Smithsonian launched an initiative to highlight women in history, based on their extensive collections. But finding women’s contributions in the archives wasn’t an easy task.

“One of the challenges with documenting the history of women at the Smithsonian is that the collections databases don’t often contain information about gender for a particular collector,” says Rebecca Dikow, Research Data Scientist at the Smithsonian Institution, in a video for Google.

And on top of that, women often weren’t referred to by their name. “They’re referred to as ‘Mrs John Smith’ instead of ‘Harriet’,” explains data analyst Lynn Cherny in the same video.

Cherny worked with the Smithsonian by creating tools to find connections between people mentioned in the archives and make it easier to filter information gathered from the records.

When Elizabeth Harmon, Digital Curator of the American Women’s History Initiative at the Smithsonian Institution, used the Google Arts & Culture tools, she was able to find a previously not well-documented connection between three women working who contributed to the science collection.

She learned that in 1911 invertebrate zoologist Mary Jane Rathbun had done field work together with scientific illustrator Violet Dandridge, and some of the specimens they collected were identified by isopod specialist Harriet Richardson.

Harmon further explored Violet Dandridge’s life via archives at the Duke University Library and discovered that she was also a suffragette.

Dandridge’s illustration skills were in demand, and she worked with several other researchers, contributing images to scientific papers and textbooks.

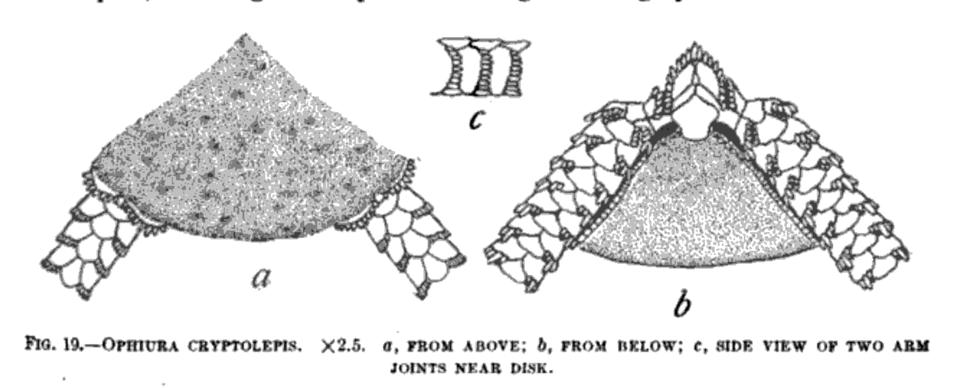

For example, Dandridge drew all the illustrations for Austin Hobart Clark’s “A Monograph of the Existing Crinoids” in 1915, and contributed a drawing of a fish to “The Fishes of Alaska” by Barton Warren Evermann and Edmund Lee Goldsborough in 1907. And in 1911, the same year she worked with Rathbun, she also contributed figures for “North Pacific Ophiurans in the Collection of the United States National Museum” by Hubert Lyman Clark.

Once you know where to look, it’s clear that Dandridge was a prolific illustrator for early twentieth century scientific texts about invertebrates and fishes. But it wasn’t immediately obvious, because contributions of women to science have not always been well-documented in the past. This collaboration between the Smithsonian and Google shows that there are likely many other stories of women in science waiting to be discovered.