The scar first appears on Annie Bonelli’s TikTok on March 18, 2021. In the video, she is in a car, earbuds in, lip-synching to the song “I Know,” by D. Savage. The mark on her cheek is blurry and soft, like a smudge of dirt. She is bobbing her head underneath a caption about how it feels when someone accidentally likes a social-media post that’s more than a year old. The lyrics offer the answer: “You say you hate me but you stalk my page, you fucking hypocrite,” Bonelli mouths.

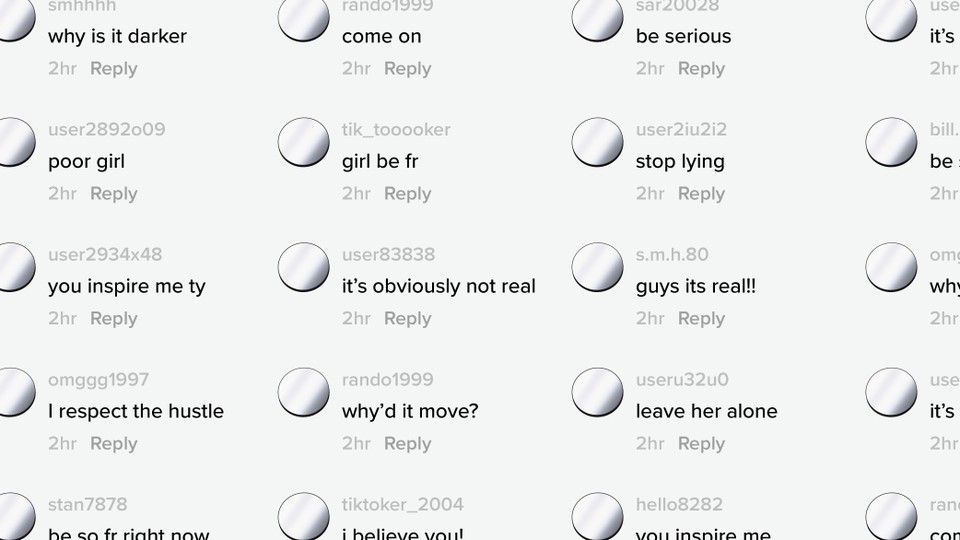

The comments section is filled with thousands of people pretty much admitting to doing just that. For nearly two years, hordes of sleuths have fixated on Bonelli’s face, united in a mission that has sent them scrolling through years of the teenager’s TikTok videos and back to this video in particular, where her mark is visible for the first time. They want to know the truth: Is the pretty, blond 18-year-old’s facial scar real, or did she fake it for online attention?

The mark on Bonelli’s face has exhibited atypical scar behavior, such as changing in color and shape in unexpected ways. It fades, only to come back a dark brown; the angle of its curve seems to shift between posts. Bonelli maintains that the scar is real, attributing its changing look to a chemical burn she got while trying to fade the original scar. But that hasn’t satisfied vigilantes, who have scoured her TikTok and Instagram pages for clues, creating compilation videos showing the scar evolution and overlaying images to compare befores and afters.

Bonelli posts all kinds of standard teenage TikTok fare—lip synchs, videos with friends, commentary about relationships—but the internet has come to know her primarily for her mark, branding her as “Scar Girl.” Dermatologists and plastic surgeons and chemists and podcast hosts and amateurs alike have weighed in. Someone made a filter that allows TikTok users to add a version of Bonelli’s scar to their own face. Videos about “Scar Girl” have accrued more than half a billion views on TikTok alone. Last week, Rolling Stone sent two reporters to the teenager’s college campus to investigate in person. Bonelli has addressed the controversy several times in different ways: defending herself, criticizing those making fun of her, crying, cracking jokes. On a recent episode of Barstool Sports’ BFF podcast, a giggly Bonelli, hair perfectly curled, jokes at one point, “What scar?” (Representatives for Bonelli did not respond to my request for comment.)

Nothing about this seems good or healthy. Think too long about “Scar Girl,” and you will feel like you are losing your grip on reality. Why don’t we have an answer yet? Why has this dragged on for so long, and why are so many people involved? You will begin to question everything about the way our modern internet is set up. Whether the scar is real or fake fades in importance, and is replaced by a much more disturbing question: Why is the internet obsessing over an 18-year-old girl’s face?

Bonelli, it’s worth saying directly, is not a famous person—or rather, she is not famous for anything other than her scar. She is a freshman at High Point University, in North Carolina, with more than 800,000 TikTok followers (100,000 of which she has gained in the past two and a half weeks). She declines to say how she got the initial scrape, at times referring vaguely to a “traumatic injury.” Pre-scar, she wasn’t—and, by traditional definitions, she still isn’t—an influencer. “TikTok was always a thing [for me], but to actually try to be an influencer, that wasn’t really ever my path,” Bonelli told Rolling Stone. “It kind of just happened.”

Random internet fame happens all the time, but “Scar Girl” projects two different, unsettling narratives about the internet and our attention economy. In one, a teenager has drawn a line repeatedly on her face for clout, and a complacent online ecosystem has allowed her to prosper. In another, a young person dealing with a true facial difference has been bullied by strangers.

The fact that Bonelli was posting on TikTok, rather than Facebook or Instagram or Snapchat, is notable if unsurprising. Her story has clearly driven a lot of engagement on the platform, which its algorithm might have taken as a signal to boost it out to bigger and bigger audiences. The centralized nature of the app’s “For You” page means it can pluck any video from any random person and make it go viral. TikTok is a place where creators and regular people alike play to the world, not just their school or community.

But algorithms alone can’t explain this level of interest. “In general, I tend to think that the way we think about social media overstates the role of the algorithms,” Kevin Munger, a political scientist at Penn State University who has studied TikTok, told me. “Algorithms reinforce the tendency for popular things to get more popular.”

Perhaps “Scar Girl” is best understood as a mirror. She reflects back at us not only the internet and the platforms we have built on it, but more fundamental questions about who we are and what we expect from others. “What distinguishes internet celebrities from traditional celebrities is this idea that they’re authentic, that they’re more honest,” Alice E. Marwick, a communications professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, told me. When that trust seems broken, audiences may feel betrayed, and lash out in response. Playing out alongside the “Scar Girl” drama on TikTok is another scandal about whether a beloved makeup influencer used a pair of false lashes while promoting a mascara brand. The internet’s desire for authenticity could have waned “now that we realize that everyone is performing all the time,” Munger said. Instead, “the obsession with authenticity has become more real.”

So maybe it’s worth interrogating ourselves here: Why has the idea that a teen might lie for attention gotten under so many people’s skin? “It’s also bringing up a really important conversation that we all need to be having with ourselves,” Robyn Caplan, a senior researcher at the Data and Society Research Institute, told me, “which is: When does our own behavior—how we act online—slip past this area of acceptability?” Even if she is lying, at what point is a teen girl’s life simply not deserving of this level of scrutiny? Teens, after all, have wanted to be famous and lied about stupid things since time immemorial. And what if she’s not lying? At what point would this become harassment?

That a simple scar has even approached the question of internet harassment is perhaps an indication that people see the truth as a moral issue: If she’s lying, Bonelli would be exploiting the real experiences of people with facial differences for attention. “There’s a lot of evidence that moral outrage spreads internet content faster than anything else,” Marwick said. This tendency to convert outrage into viral posts is both a power and a problem with the modern web: Sometimes the way anger travels online can help correct injustices; other times, a bad actor can exploit it to spread harmful mis- or disinformation.

And there’s another, less outrage-driven explanation for all the attention on “Scar Girl”: The internet loves a shared mystery. The comments sections under Bonelli’s videos are filled with people sharing their opinions on the case and cracking jokes about being nosy. This behavior, which has played out again and again, can turn into something a little more dangerous—a thrill that leads people to lose sight of the fact that Bonelli is just a college student. “I feel like on social media people get so comfortable, especially with influencers in general, to make comments on things because they don’t always view them as real people,” Bonelli told NBC News. “Like, I’m a real person.”

The more I looked into “Scar Girl,” the more I began to worry that I was just amplifying all of these problems. In my conversation with Munger, both of us acknowledged our roles in the “Scar Girl” news cycle: as the journalist following a digital trend, and the person who answered my call. Popularity, he explained, is built into the current structure of the web. Our biggest social-media platforms often reward likes, comments, and shares or prioritize scale above all—in this case, allowing what might have once been local gossip to reach millions of people.

But that version of the internet doesn’t necessarily have to be the future. Facebook and Instagram are faltering, and who knows what will become of Twitter? My colleague Ian Bogost has argued that the age of social media is ending. “It feels like we’re at a moment of rethinking the internet,” Munger said. Maybe there’s a better way forward. Maybe there’s a world in which a teenager’s face doesn’t become a national debate. That is, if we have the self-awareness to get there.