Turkish nationalists are calling on the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to revoke the passport of Archbishop Elpidophoros of America, the highest ranking Greek Orthodox cleric in the US.

As a Turkish citizen, the archbishop is one of the few clerics eligible to become the next Patriarch of Constantinople. The holder of this position is often called the “spiritual leader” of Eastern Orthodox Christians, though this status is contested.

Critics of Elpidophoros believe he should be stripped of his Turkish citizenship for repeatedly referring to the Patriarch of Constantinople as “ecumenical”. This, which means the position represents a number of different Christian Churches, is a nod to the potential global authority of the office. Turkey does not recognise the patriarch’s ecumenical status.

They also criticise Elpidophoros for using the name Constantinople instead of Istanbul (most recently during a Greek Independence Day celebration at the White House). This was the name of the city when it was the capital of the Ottoman empire.

The situation might seem somewhere between petty and parochial – the concerns of a small and relatively unimportant corner of the world, or a momentary flare-up in the Greek-Turkish conflict. But this could not be further from the truth.

The Patriarchate of Constantinople is a critical player in two volatile regions: the Middle East and eastern Europe. Both Turkey and Russia, regional powers in these unstable areas, have made religion a central component of their propaganda.

They have each sought to present themselves as the guardian of their respective religious tradition, despite having spent much of the 20th century in various forms of state-sponsored hostility to religion. For Russia and Turkey, the Patriarchate of Constantinople stands as an obstacle to their preferred narratives.

Religious politics

Russia under Vladimir Putin and Turkey under Erdoğan have become deeply invested in promoting themselves as the guardians of traditional Christianity and Islam, respectively. By leveraging this position, they have garnered sympathy and support among people who were once indifferent or even hostile to them.

Influential conservative commentators in the US such as Tucker Carlson and Rod Dreher have praised Putin’s “anti-woke” rhetoric. And some ultraconservative American men are reportedly converting to Russian Orthodoxy.

Turkey, for its part, began establishing mosques and training imams abroad, including in western Europe, as early as the 1970s. But in the past 23 years, under the rule of the Justice and Development party (AKP), it has significantly expanded these efforts.

The enemies Russia and Turkey claim to combat are both internal and external. Putin, Erdoğan and their aligned clerics, have been vocal in their denunciation of western “decadence”. This is usually represented by the liberal sexual and gender politics of western nations.

Yet they have been just as adamant in opposing those within their own traditions. In Russia’s case, this has meant perceived liberalisers largely situated in the Hellenic world – not just the Patriarchate of Constantinople, but also the Patriarchate of Alexandria, as well as the Churches of Greece and Cyprus.

For Turkey, this internal enemy has primarily taken the form of Saudi-backed Wahhabism, a strict, ultraconservative form of Sunni Islam.

The international religious influence of Russia and Turkey depends on a specific national narrative. Russia must be not only a historically Orthodox nation, but the leading Orthodox nation – the rightful inheritor of the eastern Roman world.

Likewise, Turkey must present itself as an explicitly and entirely Muslim nation, the heir to an Ottoman empire reimagined as far more homogeneous than it ever truly was.

This requires both countries reject much of their 20th-century history. Neither Soviet communism nor the strict secularity of Turkey’s founder, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, fits the current plot. It also demands the rewriting of medieval and early modern histories.

And for both, the Patriarch of Constantinople poses a significant problem. This is especially true if he is seen as anything more than a local ethnic leader, hence the objection to the use of “ecumenical” in his title.

If the Patriarch of Constantinople is a global religious leader, then Moscow is not the undisputed head of the Orthodox world, nor is Turkey a homogeneously Muslim nation with a homogeneously Muslim past.

Why the next patriarch matters

Patriarch Bartholomew, the current Patriarch of Constantinople, ascended to the throne in 1991. He has been a moderate and modernising force in the Orthodox world and beyond. Bartholomew has championed issues such as environmentalism, inter-religious dialogue and human rights, while also opposing Russian aggression in Ukraine.

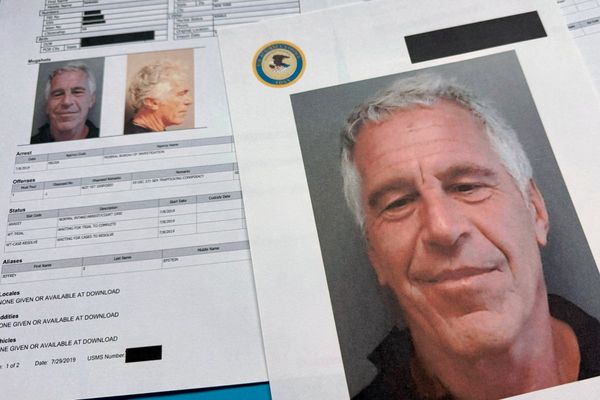

Now Bartholomew is 85 years old, the conversation has turned to the question of his successor. The options are limited, as the next patriarch must be a Turkish citizen.

If the patriarchate is to continue serving as a kind of opposition to Russian and Turkish expansionism, the next leader must also be a moderate. Should a more reactionary figure take the office, there is a real danger this counterbalance will be lost.

For those who hope to resist Russian and Turkish aggression and to promote values such as human rights in the Orthodox world and Middle East, there is simply no better choice than Archbishop Elpidophoros.

He has challenged Russian expansionism in Ukraine, defended democracy and pluralism and has taken a pastoral approach to the inclusion of LGBTQ+ people and women in the Church.

Though the patriarch is a relatively obscure position in global terms, it is precisely because of the current global situation that there may be no more important religious leader than one who can exert influence across eastern Europe and the Middle East.

The fact that allies of Putin and Erdoğan have joined in attacking Elpidophoros suggests not only that they do not want him to become the next Patriarch of Constantinople. It also suggests that western democracies should take a deep interest in who does.

The patriarchate is a rejection of the historical lies upon which both Russian and Turkish soft power rest. Thus, the man who occupies the office must be up to the task.

Katie Kelaidis does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.