Growing up in rural Devon, I was introduced to its more remote villages, farmsteads and communities as a boy. In later life, I became interested in the food traditions of these places – finding out what was eaten, and how it was prepared and cooked. This became an important aspect of my research on the evolving relationship between food and tourism in Devon.

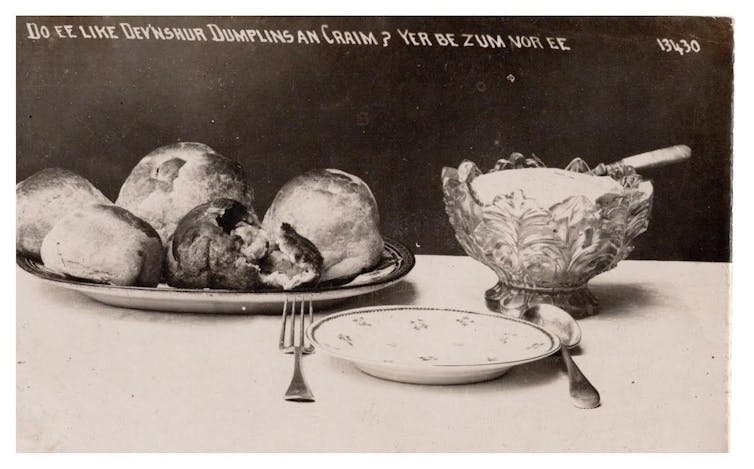

The food eaten in rural Devon up to the 1960s might appear frugal to us today, but it comprised of wholesome simple dishes. For example, Devonshire dumplings – apples wrapped in pastry and baked – were especially good when accompanied by a generous dollop of clotted cream.

Food was typically seasonal and sustaining, and fuelled hard work – especially through cold and often wet winters when a freshly baked “teddy cake”, prepared from mashed potatoes, flour, sugar, suet and dried fruit, made a welcome appearance at teatime.

I heard stories from family and friends of special food for Sundays – usually a roast dinner. And at teatime, perhaps something special like a “frawsy of junket” (milk set with rennet) or “thunder and lightning” – bread generously spread with clotted cream and anointed with treacle.

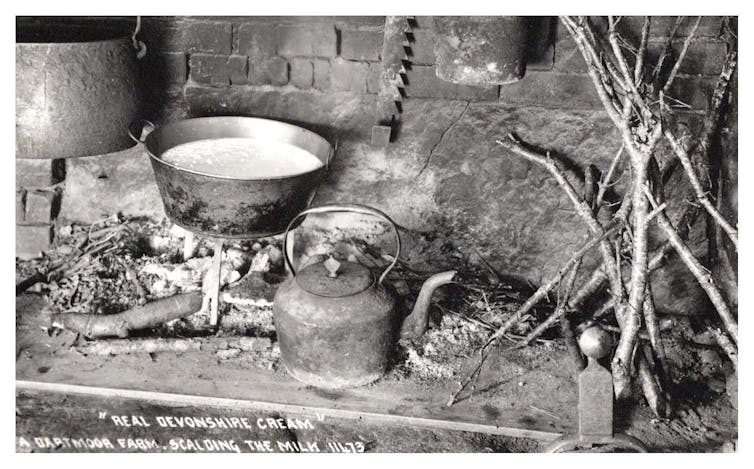

Before the introduction of coal- or wood-fired kitchen ranges and oil stoves, much cooking in Devon was done over an open hearth, with the bread oven fired up once a week for baking day.

Without refrigeration and mains water, preparing meals, baking and making clotted cream and butter was hard work. Clotted cream was a three-day process – milk was allowed to stand overnight in a cool dairy, then gently heated to form the thick crust of the cream the next day, which was carefully removed on day three.

Devonshire food and tourism

Devon’s farmhouse kitchens and food featured on postcards taken by enterprising early 20th-century photographers. With their humorous captions in Devonshire dialect, postcards were popular with visitors and now provide a visual record of what was eaten.

As transport by rail and road improved in the 19th and 20th centuries, more tourists were able to discover Devon’s resorts, moorland and countryside – as well as its food.

The John Keats poem Teignmouth, written in 1818, tells of how “you may have your cream all spread upon barley bread”. Devonshire teas evolved to become the now-ubiquitous cream tea, but its origins were the staple food stuffs of “splits”, sometimes known as Chudleighs – small buns made from a yeast dough, eaten with clotted cream and jam or honey.

The British author Douglas St Leger Gordon, writing in the 1950s, lamented the decline of Devon’s harvest teas, which involved rural rituals and ceremony. Traditionally, the farmer’s wife and daughters would host a feast for all who had helped with the harvest, usually comprising ham sandwiches, homemade cake, splits spread with cream and jam, and specially baked harvest buns – “all of which appeared as if by magic”. The food and tea was carried in baskets to the hay-field, and the sharing of labour was rewarded with farmhouse hospitality.

Devon’s larder of fine food was known out of the county, too. Devonshire butter was sold in Fortnum & Mason in London from the 18th century, and during the 1920s The Devonshire Dairy on Oxford Street traded butter and cream.

The word spread through cookery and travel books, too. In Alec Adair’s recipe book Dinners Long and Short (1928), salt cod fried for breakfast, apple-in-and-out (a baked pudding made with apples, suet, sugar and flour) and Devonshire fried potatoes appear alongside classic French cuisine.

Clovelly herrings, or “silver darlings”, feature in Murray’s Handbook for Travellers in Devon and Cornwall (1859), which recommended visitors should stay in the cliffside village to “regale at breakfast on herrings which have been captured overnight”, and are at their best in autumn.

Some of the more intriguing Devon recipes, alas, were not recorded for posterity. We can only imagine the dish that in his journals, Reverend John Skinner called the “squab pie”. It was “four feet in circumference … composed of neck of mutton, apples and onions, and by no means a bad thing”.

Devon’s food tells an evolving story of tradition, and a culinary and cultural relationship with landscape, communities and seasons. It is a celebration of regional food heritage and history – a legacy I hope, through my research on Devonshire food and cookery, to share with future generations.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

Paul Cleave does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.