Romeo Is a Dead Man is the game where Suda51 fully embraces the absurdity he’s known for — a beloved, rebellious creator fully going off the deep end, in the best way possible. If you’ve played any of Goichi Suda’s games (No More Heroes, Shadows of the Damned, Killer7), you know his works have a distinct, oftentimes antagonistic style, and boy does that describe Romeo Is a Dead Man. This feels like the game where Suda fully and completely leans in — you’re either in for the ride with his style, or you’re not. And for my money, Romeo Is a Dead Man is already one of the most fascinating games of the year. It’s a violent Technicolor fever dream of a game that seeks to surprise and delight you at every turn, while simultaneously tackling the absurdity of our obsession with the multiverse. And boy am I absolutely dying to play the full thing.

I want to fully admit that I’m not quite sure how to properly convey the experience of playing Romeo is a Dead Man. That’s because this game is genuinely unlike anything else I’ve ever played in my life — it has bits of things like No More Heroes and Killer7, but stands entirely distinct. But what I do know is the game viciously hooked me after roughly four hours of playtime — so much so that I’d legitimately pay good money to simply play it right now. It’s partially an action-brawler with light Soulslike elements, it’s partially a platformer collectathon, and it’s partially a 2D minigame fest. Romeo is a Dead Man is a lot of things.

In the first ten minute you’re introduced to a flood of plot points that set up Romeo Is a Dead Man, which all feel intentionally overwhelming and scattershot. A certain event has ripped space and time apart, and the small Northwestern town where Romeo Stargazer happens to work as a deputy just happens to be the center of it all. After being mauled by a horrific monster, Romeo’s brilliant scientist uncle uses his time machine to arrive at just teh right moment and use a device to turn Romeo into “Deadman,” a kind of undead superhero.

As it turns out, just days before this, however, Romeo had found a woman collapsed on the road, named Juliet, and fallen in love with her. But wouldn’t you know, Juliet turns out to be an evil multiversal villain threatening the collapse of spacetime, and so with his new Deadman power,s Romeo is recruited by the FBI’s Space-Time Police to, well, save all of existence.

I promise I’ve described the story setup as succinctly as possible, but as you might have gleaned, the first few hours of Romeo is a Dead Man are a complete fever dream. But while it throws ever-increasingly bizarre things at you, the game does establish its formula fairly early on.

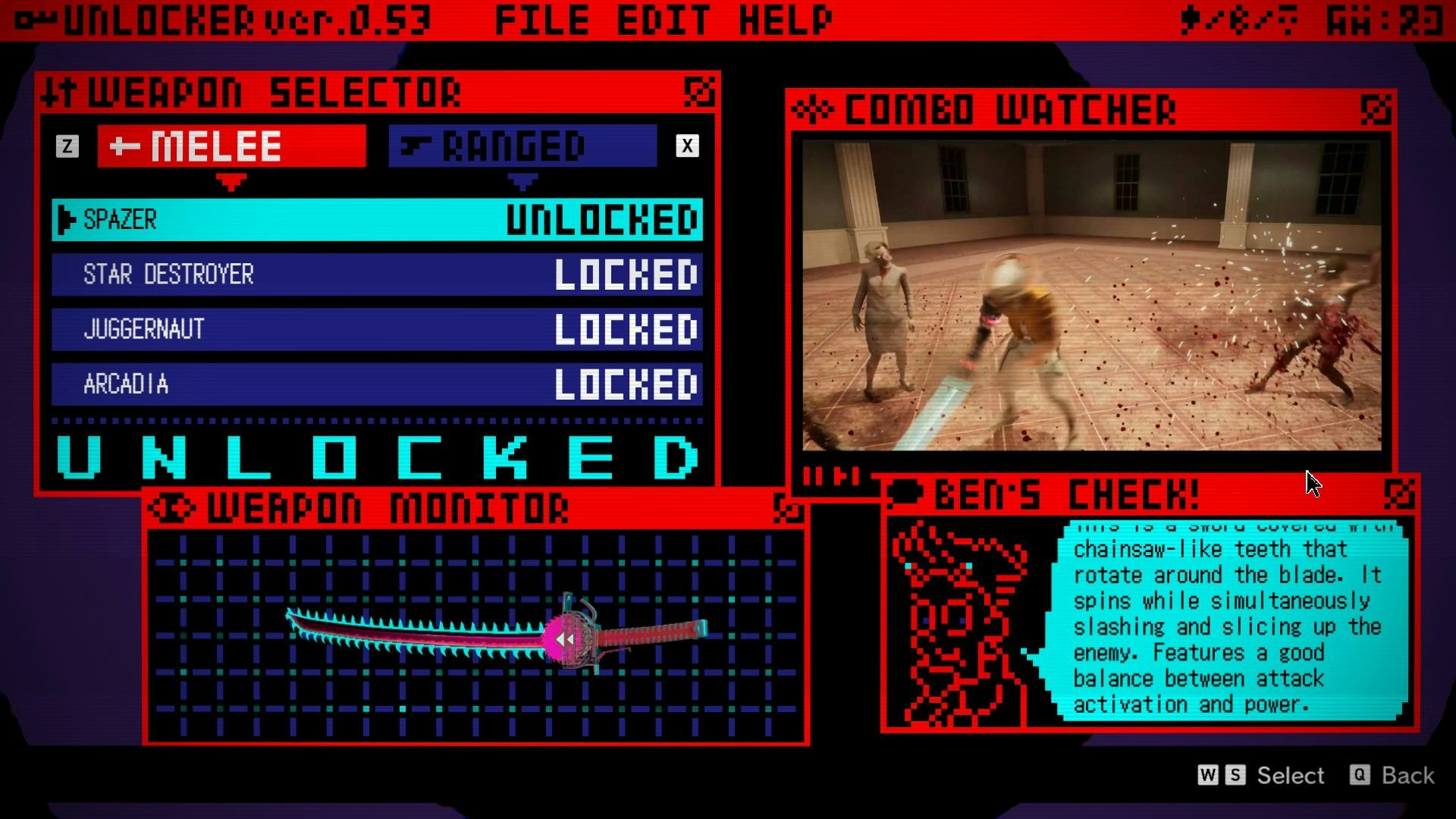

Romeo Is a Dead Man is essentially an “episodic” game, where each episode has you diving into different eras of time to take down a space-time villain. These episodes feel a lot like missions from No More Heroes, where you explore an area as Romeo and hack apart a bunch of zombie-like enemies in action combat. Romeo has a variety of different melee and ranged weapons you can unlock, and combat is heavily focused on combos and dodging enemy attacks — with a ton of visual flair and blood spray that can almost be overwhelming. But as you attack, a blood gauge fills, letting Romeo use a “Bloody Summer” attack, a variant on your melee or ranged weapon that causes huge damage and can quickly turn a bad situation around.

But the areas you explore are also strewn with collectibles and items that you can use to cook up dishes at your base, improve Romeo, and more. The first level I played was a murky swamp filled with explosive barrels, while the second was a neon-infused 1980’s shopping mall (that felt a lot like Dead Rising). These areas are filled with visual flair, but also packed with little puzzles and things to break up the flow.

In the first level, I stumbled upon a TV that housed some kind of seemingly paranormal entity. Reaching through the TV, the entity sent me to the “end of time” to gather the pieces of a key I needed, which then unlocked the way to a boss — which happened to be a monstrous “variant” of Juliet that transformed into a horrific creature quite literally named Everyday is a Monday.

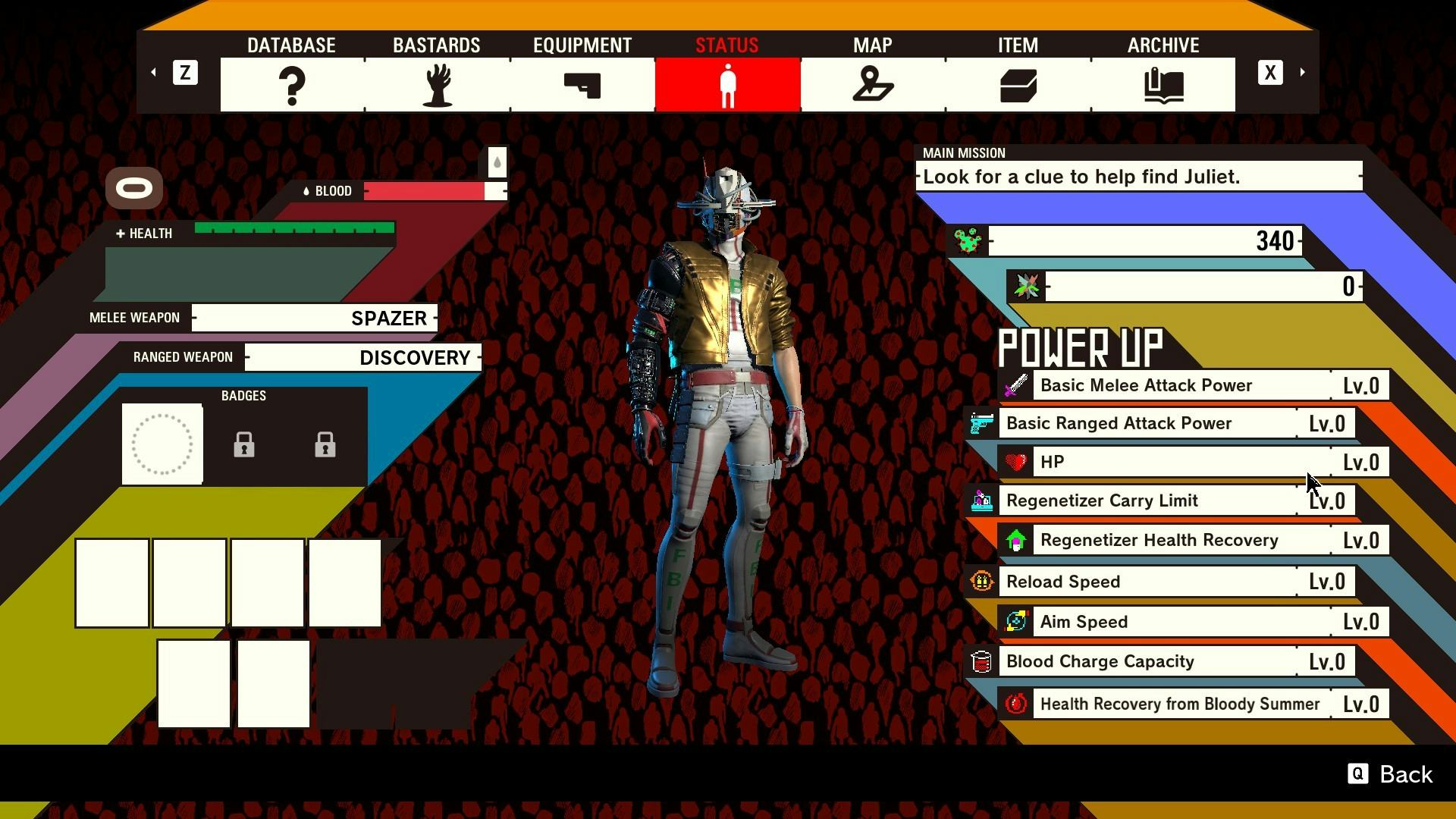

The action and exploration in Romeo Is a Dead Man feels great, most comparable to Suda’s No More Heroes game, in a good way — but the biggest surprise is your home base between ships. Themed as a retro-2D game, the FBI ship houses all your upgrade facilities, and it’s also one of the most fascinating experiments I’ve seen in video game menu and UI design.

Every single facet of the ship sports some kind of unique menu. The cooking minigame is literally real-life footage where you dunk things in a fryer. Upgrading weapons is like tuning a 90s boom box. And you can plant seeds to grow zombie creatures called “bastards,” which you then deploy in combat like little Pokémon helpers. And so much of Romeo Is a Dead Man gamifies little menu elements. My favorite is that as you collect a major resource, you can pump it into a rocket ship that you fly around a little Pac-Man maze, collecting nodes that increase Romeo’s stats. And the maze is persistent, meaning you pop back into it and continue where you left off.

I simply cannot overstate how eclectic the visual style of this game is, but how much it all kind of just works together. It’s unlike anything I’ve ever seen, and like with the cooking minigame, there’s a handful of real-life practical effects jarringly thrown in, including one of the most horrific death screens I’ve ever seen in a game.

In some ways, playing Romeo Is a Dead Man feels like stepping into a modern art exhibit, waiting to see what the next wild design is, and whether it goes over your head or not. And all of it fits Suda and Grasshopper Manufacture’s style to a tee — it’s weird, wild, befuddling, and intoxicating all at once.

Like arthouse films, Romeo Is a Dead Man feels like a game that absolutely won’t appeal to everyone, and its unorthodox setup and energy could easily turn some players off. But that’s exactly the point. This is a Suda game, and Suda only cares about pleasing the people who have already bought into the formula, the Kool-Aid, if you will.

But amidst all the shock factors and shlock, it feels like there’s some real commentary going on in Romeo Is a Dead Man, on the absurdity of our obsession with multiverses and timelines — and even how we consume and digest art.

This is a visionary studio and creator at their most experimental, and I’m already hoping something generational might come from it.