Poet, novelist, piano player. And that was before Gil Scott-Heron had reached 20. He wrote and recorded his best known song, The Revolution Will Not Be Televised, in 1971, and from then on produced a unique and polemical body of prose, poetry and music that led him to be dubbed the "Father of Political Rap", the originator of "nu soul" and many more titles. He preferred being called a "bluesologist".

When he died suddenly in 2011 at the age of 62, there was a sense of shock that Gil had left this world with his career unfinished. His return to stage performances and poetry in his later years after being jailed for drug offences led to the release of the album I'm New Here in 2010, his first record for 16 years. It was rapturously received and in recognition of his work and career, he received a posthumous Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 2012.

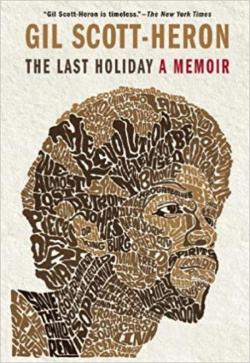

At the time of his death, Scott-Heron was working on a memoir, a project he had been working on for years. Cobbled together by his publishers from odd bits of paper, manuscripts and files, the memoir was finally published in 2012 under the title, The Last Holiday (Grove Press, 2012); the book was published as a paperback in 2017, and I found my copy recently in one of Bangkok's book stores.

Some commentators have compared The Last Holiday to Bob Dylan's Chronicles: Volume One as both books consider some of the "old-time America" that turns up in their music. Where Dylan charts the influences of Woody Guthrie and genres like bluegrass, Scott-Heron crosses town to delve into the African-American experience, with blues music as his default starting point; the blues connection and literature was brilliantly explored by Harlem renaissance man and poet Langston Hughes, and Scott-Heron notes in his book how influential Hughes was on his music and poetry. For those of you wondering what a bluesologist is, Scott-Heron defines it thus: "A scientist who is concerned with the origin of the blues."

Although the memoir is slim, it is packed with the details that surrounded Scott-Heron's life -- from his early years in rural Tennessee, where he was sent to stay with his grandmother (his Jamaican father had abandoned the family to cross the Atlantic to play football for Celtic in Scotland, thereby becoming the first black footballer in Scottish football) and returning to live with his mother in Brooklyn. He not only tells us about his early years -- the love of learning instilled in him by his grandmother, the refusal to bow down to bigotry by his mother -- he also explains how important were the strong women in his life.

At the same time, Scott-Heron situates his life in the African-American experience of post-World War II life in America (play Winter In America if you want to get an idea of this process). He is able to weave this into a story which also includes his touring with Stevie Wonder in 1980 as Wonder went around the US to drum up support for a national holiday to celebrate the life of Dr Martin Luther King. Scott-Heron was the opening act for the tour and his respect for Wonder is evident.

The writing is at times a bit inconsistent and scratchy, after all the manuscript was incomplete, but when he gets down to describing his early experiences, the poet soon emerges. For instance, most writers would avoid alliterations like this one, on his grandmother, who "scrapped, scrimped, scrambled, scrunched, scrubbed, scratched, scuffled, slaved and saved until somehow all four of her children had graduated from college with honors". But somehow, with Scott-Heron, these passages and their flights of fancy read so well.

As the book ends in 2000, we are left wondering about Scott-Heron's drug addictions, his children and his failed marriages. Perhaps these most painful details are what he would have written about last; had he lived we might have understood more about these demons that cut short his life.

But I can't recommend this book highly enough. Scott-Heron was, without question, one of the best songwriters of his generation. Hard-hitting songs like B-Movie (for anyone who wants a critique of US electoral politics), Whitey On The Moon, We Almost Lost Detroit, Angel Dust and Home Is Where The Hatred Is are as relevant in these dark times as they were when they were first released. Uplifting tunes like Lady Day And John Coltrane sound as fresh today as they did back then, too. The revolution may not be televised (hey, we've got social media now) but Gil Scott-Heron will be watching from the wings. You can be sure of that.

- To celebrate the 25th anniversary of World Beat in style, please join me this Thursday night at Studio Lam on Sukhumvit 51 for a World Beat party of epic proportions.

- Todd Tongdee's "Rhythm Of The Earth Festival" returns in Phetchaburi province on April 7-8 with a stage that showcases local Thai Dam musicians as well as bands and musicians from Africa, the USA and the Middle East.

John Clewley can be contacted at clewley.john@gmail.com