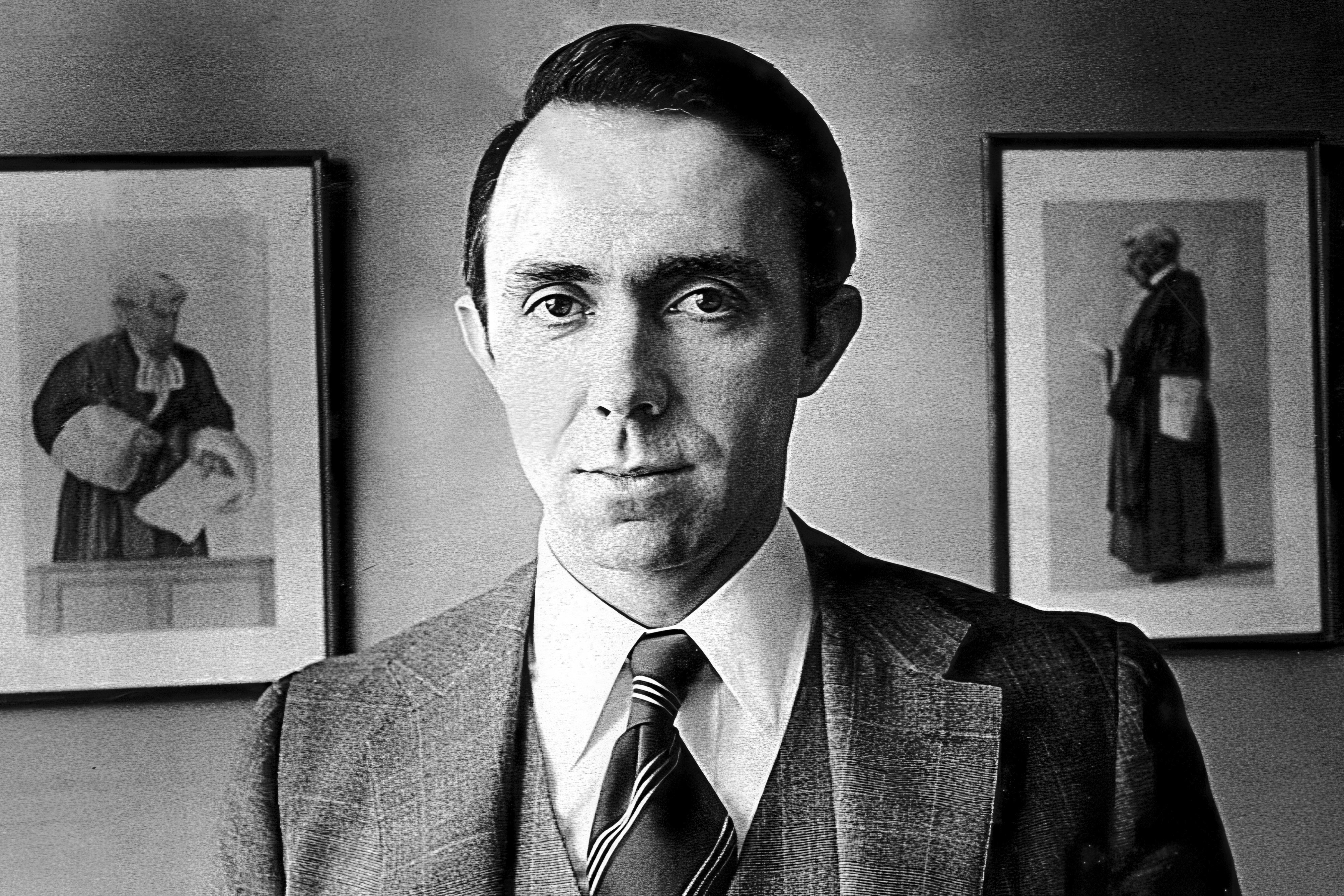

Justice David Souter, a quiet and iconoclastic jurist who spent nearly two decades on the United States Supreme Court from 1990 to 2009, has died at age 85.

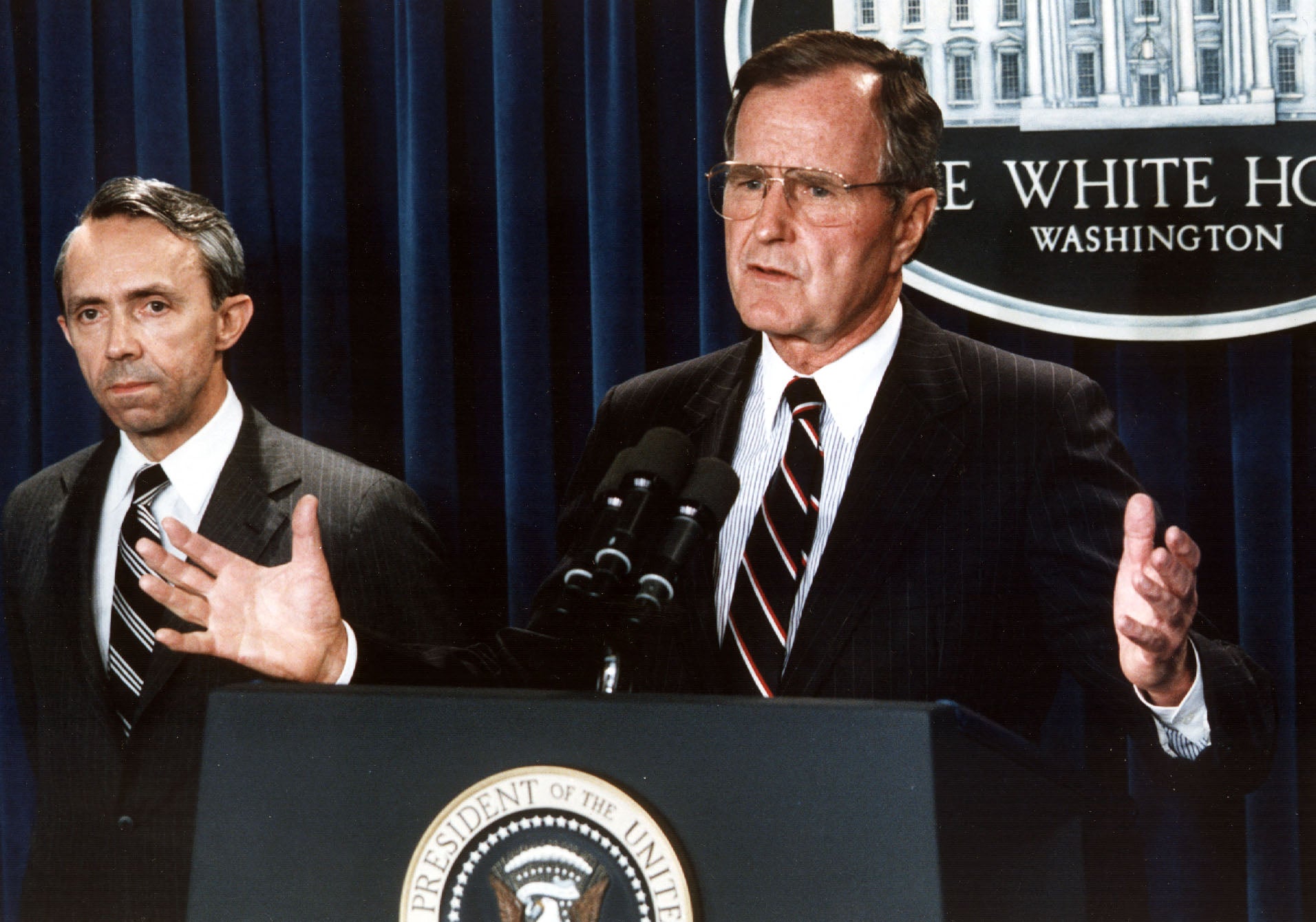

The New Hampshire-born attorney was named to the highest court in the U.S. by then-president George H.W. Bush, who sought a conservative replacement for Justice William Brennan, an icon of the court’s liberal wing. But Souter’s time on the court revealed him to be more pragmatic than ideological as he shifted to the center, often voting with the court’s liberals in abortion-related cases that made him a pariah in right-wing legal circles.

In a statement, Chief Justice John Roberts praised his late colleague as having “served our Court with great distinction for nearly twenty years” and said the Granite State resident had “brought uncommon wisdom and kindness to a lifetime of public service.”

Roberts also praised Souter for spending roughly 10 years of retirement as a part-time judge on the Court of Appeals for the First Circuit and said his former colleague would be “greatly missed.”

David Hackett Souter was born on September 17, 1939 in the town of Melrose, Massachusetts but spent the vast majority of his childhood — and his life — on his family’s farm in Weare, New Hampshire.

After attending New Hampshire public schools, he matriculated at Harvard University and earned a bachelor’s degree there in 1961 before accepting a Rhodes Scholarship that took him to Magdalen College, Oxford. There, he earned an A.B. in Jurisprudence and a Master’s degree in two years, after which he returned to Harvard Law School for a three-year period of study to earn a Bachelor of Laws.

Souter was admitted to the bar and began practicing law at the Concord, New Hampshire firm of Orr and Reno as an associate attorney. But he turned to public service in 1968 when he accepted a job as an Assistant Attorney General of the Granite State. Three years later, he was New Hampshire’s Deputy Attorney General, and by 1978 he was the Attorney General of New Hampshire, the state’s chief law enforcement officer.

His meteoric rise through the profession continued when he was selected to be an Associate Justice of the New Hampshire Supreme Court in 1978. He would spend the next 12 years on that court, including the last seven as Chief Justice, before then-president George H.W. Bush nominated him to serve on the First Circuit. He took his seat on the Boston-based court in May 1990.

But Souter did not remain in Boston for long. Brennan, the outspoken liberal who’d been a stalwart of the high court since 1956, suffered a stroke and announced his retirement from public service.

Bush, whose close friend and chief of staff John Sununu had selected Souter to be a justice on New Hampshire’s top court during his time as governor, successfully advocated for him to be elevated to the nation’s highest court as a replacement for Brennan with the aim of tilting the court’s ideological balance to the political right.

After a confirmation hearing, the United States Senate voted to confirm Souter as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court Court by a vote of 90 in favor and just nine against, leading to him being sworn in to office on October 9, 1990.

At first, Souter’s output on the court placed him firmly in the court’s growing conservative bloc, led by Chief Justice William Rehnquist and Justice Antonin Scalia. But after Bush’s 1992 selection of Justice Clarence Thomas to replace another liberal icon, retiring Justice Thurgood Marshall, Souter made a marked shift towards the center by voting with the court’s liberals against permitting prayer at a public high school graduation ceremony.

It was in the 1992 case of Planned Parenthood v. Casey that Souter’s centrist shift made his name a reviled one among conservatives.

Anti-abortion activists had hoped that the additions of Souter and Thomas to the court would permit the justices to overturn the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision that had legalized abortion across the country.

The case had been brought by a group of abortion clinics and physicians who’d sought to overturn a Pennsylvania law that placed multiple restrictions on the procedure. It was the first opportunity for justices to overturn Roe since Brennan and Marshall — both strong supporters of the 1973 ruling — had left the court.

Yet Souter, whose legal output up to then had never provided much of a window into his views on the abortion issue, sided with a trio of justices who supported reaffirming Roe: Justice John Paul Stevens, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, and the 1973 decision’s author, Justice Harry Blackmun.

The three justices authored a plurality opinion upholding what they called Roe’s “essential holding.” Specifically, they said women had the right to terminate a pregnancy before viability without “undue burden” from government, while any post-viability restrictions needed to have exceptions for the mother’s life and health.

His decision to keep Roe in place infuriated conservatives and led to efforts by the Federalist Society and other right-wing legal groups to ensure that future Republican presidents would choose more ideologically reliable legal activists for court seats at all levels. That stricter vetting ultimately resulted in presidents George W Bush and Donald Trump nominating justices who would overturn Roe in the 2022 case of Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization.

Souter would remain in the court’s ideological center during the 17 years he spent there following the Casey decision, though the court’s rightward shift meant he voted with the liberal wing far more than his more conservative colleagues over that time period.

One case among the many he considered reportedly had a significant effect on him, the 2000 Bush v. Gore case in which he sided with three liberals — Stevens, Steven Breyer and Ruth Bader Ginsburg — in a dissenting opinion while a five-vote majority of justices appointed by Republicans voted to end a recount of votes in Florida months after the 2000 presidential election, effectively handing the presidency to GOP candidate George W Bush.

In his 2007 book on the court, The Nine, journalist Jeffrey Toobin wrote that Souter considered stepping down from the court in the wake of the 2000 election case because he viewed the majority’s ruling as “so transparently, so crudely partisan that Souter thought he might not be able to serve with them anymore.”

He ultimately decided against resignation and remained on the court for another nine years. But Souter was never entirely comfortable living or working in the nation’s capital. While he remained there during the times of year when the court heard cases, he would always rush back to his home on the Weare, New Hampshire farm where he’d lived since childhood.

In both places, Souter was widely known to live an analog, iconoclastic existence. He never used a computer and preferred to write opinions with a vintage Esterbrook fountain pen. But upon his retirement in 2009, veteran New York Times correspondent Linda Greenhouse wrote that focusing on those eccentricities meant one missed “the essence of a man who in fact is perfectly suited to his job, just not to its trappings.”

“Far from being out of touch with the modern world, he has simply refused to surrender to it control over aspects of his own life that give him deep contentment: hiking, sailing, time with old friends, reading history,” she wrote.

Unlike many justices who remain on the court until death or only retire when they can be sure an ideological successor will fill their seat, Souter chose to stand down in mid-2009 when, according to NPR, he determined that no other justices would be retiring during that term so he could avoid causing more than one vacancy at once.

He was replaced on the court by Justice Sonya Sotomayor, but he continued to avail himself of a privilege afford to retired federal judges by continuing to hear cases and participate in deliberations as part of the First Circuit court where he’d briefly served before being nominated to the Supreme Court.

Souter did make one significant life change in his retirement, however. In August 2009, he sold his childhood home in Weare and moved from that family farm to a single-story house in Hopkinton, New Hampshire.

According to Concord Monitor, he told a neighbor that his decision to move was so he could live somewhere with floors that could support the weight of the thousands of books he had acquired over the years.

Democrats seethe over Biden’s media blitz: ‘Elections are about the future’

Washington's Hispanic community fighting fear and rallying help as rumors of an ICE crackdown bubble

Fears grow Kash Patel isn’t taking his job seriously as he skips morning briefings

ESPN panelist Kate Fagan says ‘trans kids deserve to play sports’ in final appearance

Glitz, glamour and a love of power: How Peter Mandelson won over Donald Trump

Trump’s failed Surgeon General pick lands on her feet with a job at RFK Jr’s HHS