Archaeologists are exploring the dark blue waters of Denmark's Bay of Aarhus, searching for ancient coastal settlements swallowed by rising sea levels more than 8,500 years ago.

This summer, divers descended around eight metres beneath the waves near Aarhus, Denmark's second-largest city, collecting evidence of a Stone Age settlement from the seabed.

This forms part of a six-year, €13.2 million (£11.3 million) international project, funded by the European Union. It includes researchers from Aarhus, the UK's University of Bradford, and Germany's Lower Saxony Institute for Historical Coastal Research.

The goal is to map parts of the Baltic and North Sea beds, exploring sunken Northern European landscapes and uncovering lost Mesolithic settlements as offshore wind farms and other sea infrastructure expand.

Global sea levels rose after the last ice age

Underwater archaeologist Peter Moe Astrup, who’s leading underwater excavations in Denmark, remarked that most evidence of such settlements so far has been found at locations inland from the Stone Age coast.

“Here, we actually have an old coastline. We have a settlement that was positioned directly at the coastline,” he said. “What we actually try to find out here is how was life at a coastal settlement.”

After the last ice age, huge ice sheets melted and global sea levels rose, submerging Stone Age settlements and forcing the hunter-gatherer human population inland.

About 8,500 years ago, sea levels rose by about 2 meters (6.5 feet) per century, Moe Astrup said.

Moe Astrup and colleagues at the Moesgaard Museum in Højbjerg, just outside Aarhus, have excavated an area of about 40 square meters (430 square feet) at the small settlement they discovered just off today's coast.

Rising sea levels preserved history “like a time capsule”

Early dives uncovered animal bones, stones tools, arrowheads, a seal tooth, and a small piece of worked wood, likely a simple tool. The researchers are combing the site meter by meter using a kind of underwater vacuum cleaner to collect material for future analysis.

They hope further excavations will find harpoons, fish hooks or traces of fishing structures.

“It’s like a time capsule,” Moe Astrup said. “When sea level rose, everything was preserved in an oxygen-free environment … time just stops.”

“We find completely well-preserved wood,” he added. “We find hazelnut. ... Everything is well preserved.”

Excavations in the relatively calm and shallow Bay of Aarhus and dives off the coast of Germany will be followed by later work at two locations in the more inhospitable North Sea.

The sea level rise thousands of years ago submerged, among other things, a vast area known as Doggerland that connected Britain with continental Europe and now lies underneath the southern North Sea.

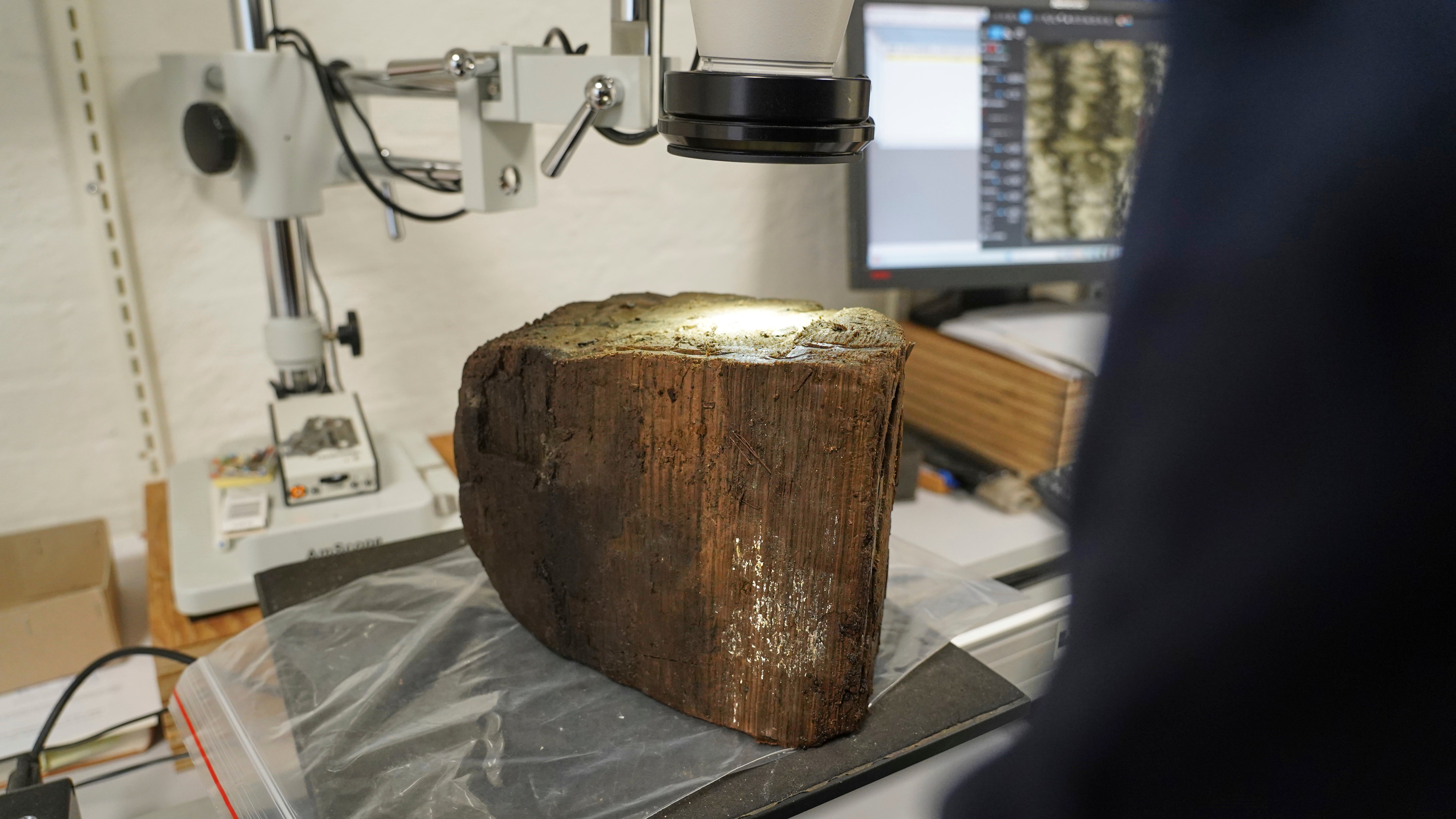

To build a picture of the rapid rise of the waters, Danish researchers are using dendrochronology, the study of tree rings.

Submerged tree stumps preserved in mud and sediment can be dated precisely, revealing when rising tides drowned coastal forests.

“We can say very precisely when these trees died at the coastlines,” Moesgaard Museum dendrochronologist Jonas Ogdal Jensen said as he peered at a section of Stone Age tree trunk through a microscope.

“That tells us something about how the sea level changed through time.”

As today's world faces rising sea levels driven by climate change, the researchers hope to shed light on how Stone Age societies adapted to shifting coastlines more than eight millennia ago.

“It’s hard to answer exactly what it meant to people,” Moe Astrup said. “But it clearly had a huge impact in the long run because it completely changed the landscape.”

Sea levels rose by a global average of around 4.3 centimeters (1.7 inches) in the decade up to 2023.

Authorities charge Afghan suspect in Munich car ramming attack that killed 2 and injured 44

A US tariff exemption for small orders ends Friday. It's a big deal to some shoppers and businesses

UK residents spend almost three times more on trips abroad than inbound visitors

Why the racist study of skulls gripped Victorian Britain

Scientists discover new dinosaur species with ‘eye-catching sail used for mating’

What the bones of an ancient child reveal about humans and Neanderthal inbreeding