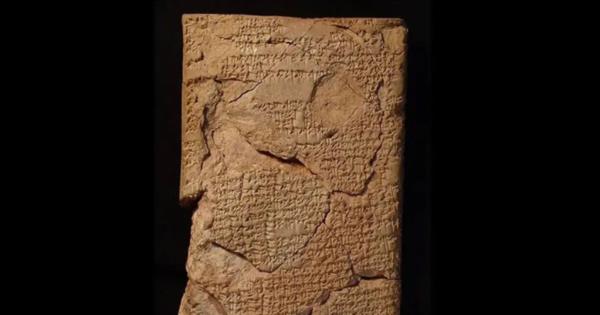

Researchers have recently decoded 4,000-year-old clay tablets discovered in modern-day Iraq over a century ago. These tablets, adorned with cuneiform inscriptions, are considered the oldest compendia of lunar-eclipse omens ever found. The Babylonians, residing in central-southern Mesopotamia, analyzed lunar eclipses to predict future events, viewing celestial occurrences as divine messages.

One tablet foretells the death of a king and the destruction of Elam, an ancient civilization in present-day Iran, based on eclipse characteristics. Another omen predicts the downfall of Subartu and Akkad, regions in Mesopotamia, if an eclipse begins in the south. The tablets also associate an eclipse in the evening watch with pestilence.

Ancient astrologers likely combined observational data with theoretical frameworks to interpret celestial omens. Advisors to the king monitored the night sky, matching their observations with academic texts on celestial omens. If a prediction indicated a threat, such as the death of a king, an oracular inquiry through extispicy was conducted to assess the danger.

Babylonians meticulously recorded celestial events, enabling astronomers to predict lunar and solar eclipses with reasonable accuracy. In response to negative omens, substitute kings were sometimes appointed to shield the ruling monarch from perceived divine retribution, with the substitute king being sacrificed in the king's place.

The clay tablets, acquired by the British Museum between 1892 and 1914, were recently fully translated and published. Originating from the ancient Babylonian city of Sippar, these tablets shed light on the Babylonians' intricate system of interpreting celestial omens and their practices to avert perceived calamities.