WASHINGTON _ On the eve of a self-imposed deadline to unveil their tax-cut bill, House Republicans were still arguing Tuesday evening over key elements, including how fast to cut corporate rates, which state tax deductions to eliminate and whether to impose new caps on popular 401(k) retirement accounts, according to people familiar with the negotiations.

GOP leaders warned they may miss Wednesday's target to release the bill text as negotiations continue, though they still planned to meet with lawmakers to discuss the latest version.

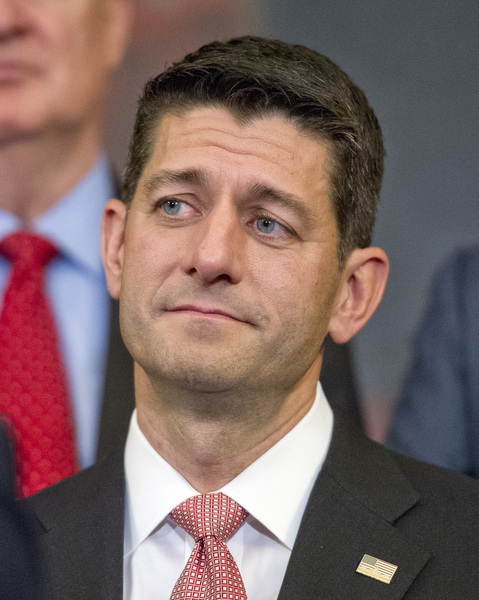

Some details were coming into focus. At a private meeting with outside conservative groups Tuesday afternoon, House Speaker Paul D. Ryan said the plan would keep the current top tax rate of 39.6 percent for the most affluent Americans, but will make that bracket apply only to "substantially" higher incomes than the current $470,700 for couples, according to participants at the gathering.

The plan will also delay the repeal of the estate tax _ long sought by the GOP _ for two to three years, the speaker told the group.

And Ryan said that though he wanted the House bill to immediately slash the corporate tax rate to 20 percent from the current 35 percent, the final version may phase in the cut.

"I can't speak to what the Senate's going to do," he told the group.

Earlier Tuesday, when asked whether the corporate rate would be dropped gradually, President Donald Trump said, "Hopefully not."

New limits were still being debated on 401(k) accounts, possibly reducing next year's $18,500 annual cap, though not to as low as the $2,400 limit previously discussed, according to those familiar with the negotiations.

Trump had said he opposed the idea and Ryan said the bill was closer to the president's preference, but Republican bill drafters were frantically searching for revenue to offset the costs of sweeping cuts elsewhere.

House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Kevin Brady, R-Texas, said caps on non-tax-deferred savings accounts, such as Roth individual retirement accounts, could be increased at the same time.

Another battle centers on deductions for state and local taxes. On Monday, GOP leaders appeared to reach a deal to maintain at least part of the individual deduction for property taxes, but eliminate the deduction for state and local incomes taxes.

That came as a blow to California, which has the highest top state income tax rate in the nation but ranks in the bottom third by one measure for property taxes, thanks to Proposition 13, which was passed in 1978.

In 2014, Californians claimed $70 billion in federal deductions for state and local income taxes but only $27 billion in real estate, personal property and other taxes, according to the California Franchise Tax Board.

Other high-tax states, such as New York and New Jersey, would fare slightly better since property taxes in those areas make up a larger share of the overall burden.

But even that agreement appeared to be in flux as GOP leaders wanted assurances from wavering East Coast lawmakers. They were continuing to haggle late Tuesday.

Other popular federal deductions, including mortgage interest, charitable giving and tax-free employer-sponsored healthcare, will remain untouched, according to those familiar with the talks.

"Tax reform is hard, by definition," said one conservative group member who attended Tuesday's meeting. "Not everyone is pleased with everything. But overall, it's going to be a pretty good tax bill."

The cornerstone of the GOP proposal is a reduced corporate rate, slashed to its lowest since the 1930s, from 35 percent to 20 percent. So-called pass-through businesses, whose owners file individually, would see rates drop to 25 percent, as outlined in a draft blueprint from Trump and the Republican majority in Congress.

Companies could bring home overseas profits, but not at the one-time low rate as first envisioned, Ryan told those at the meeting. He indicated it would be more likely at a 10 percent to 12 percent permanent rate, participants said.

Businesses could also more swiftly write off investments, with full depreciation for five years, but not longer, as some had hoped.

Individual rates would be consolidated to 12 percent, 25 percent, 35 percent and 39.6 percent, though income levels for each bracket remained unknown. In return for limiting individual itemized deductions, the standard deduction would be doubled to $12,000 for individuals or $24,000 for couples.

The child tax credit is also expected to increase.

For many tax filers, details about which income brackets will be applied to the new rates will be key to determining whether they are better off under the Republican plan.

Critics and several nonpartisan tax analysts have already predicted that the plan will mostly benefit corporations and the wealthy, though Trump has insisted his aim is to help the middle class.

Trump met Tuesday with Ryan and key industry leaders at the White House in what has become the most substantial legislative undertaking this year from Republicans in Congress. The president wants House passage by Thanksgiving with a bill signing by year end.

"The Democrats will say our tax bill is for the rich, which they know it is not," Trump said. "It's a tax bill for the middle class. It's a tax bill for jobs. It's going to bring a lot of companies in. It's a tax bill for business, which is going to create the jobs."

Republicans have been working behind closed doors for weeks with the administration as they assemble legislation in a strictly partisan exercise without Democrat input, relying on special rules to avoid a filibuster and allow for passage in the Senate with 50 votes, assuming Vice President Mike Pence breaks the tie.

A key trouble spot has been figuring out how to pay for the tax cuts, which outside analysts estimate will cost more than $2.4 trillion in lost revenue over the decade.

Analysts are skeptical of Republican assertions that much of the costs will be offset by new revenue from economic growth. Republicans have allowed for $1.5 trillion in new deficit spending to cover the tax cuts, but were struggling to stay within that limit as rank-and-file lawmakers balked at proposals to limit deductions popular with voters and special-interest groups.

Democratic Govs. Jerry Brown in California and Andrew Cuomo in New York also pressured Republicans to back off the plan to eliminate state and local deductions.

The original GOP plan was to eliminate both property and state income deductions. But East Coast congressional Republicans threatened to withhold their votes for the GOP tax bill if their residents were not protected. While some California Republicans also raised concerns, they did not play a key role in talks.

House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif., insisted Tuesday that Californians would be better off under the Republican plan even with the new limits.

"I believe at the end of the day, when you look at the entire tax package ... people will see there's a savings," McCarthy told reporters on a conference call. "I think Californians win in this."

Congress has not passed a substantial tax overhaul in 30 years, but Republicans, after the breakdown this year of efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act, have made passage a top priority, especially as they head into next year's midterm election.

Pressure runs high for Republicans to deliver on campaign promises now that they control the House, Senate and the White House, which is why some lobbyists and others say they have maintained such a closely held process.

"Republicans need a win on policy, on a legislative level, and this is the best chance," said one official from a major trade industry group familiar with the negotiations.