“A sound strategic idea, but marred in the execution” was the Manchester Guardian’s view in 1916 of the tragic events at Gallipoli the previous year, now widely regarded as one of the allies’ greatest defeats of the first world war.

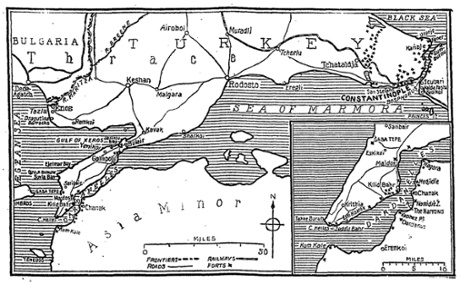

Conceived in early 1915 by Winston Churchill in order to overcome stalemate on the western front, the allies’ intention was to capture the Dardanelles straits from the Ottoman Empire which had recently entered the war on the side of Germany, thereby facilitating the safe passage of Russian warships from the Black Sea. An unsuccessful naval attack was followed by a land campaign headed by general Ian Hamilton. The first ill-fated landings on the Gallipoli peninsula by British, French, Australian and New Zealand forces occurred on 25th April 1915.

In the early stages of the war the government had banned reporting from the front line. Some journalists defied the ban but they could face severe penalties if their writing was perceived to undermine morale or assist the enemy. Newspapers therefore relied significantly on official reports provided by the military.

Informed by an official dispatch the Manchester Guardian summarised on 27 April that the allied troops had “despite a stout resistance from the entrenched enemy, made good their footing” on the peninsula. Yet the allied forces had underestimated the preparations of the Ottoman forces and their unfamiliarity with the harsh terrain also worked against them. Both sides suffered significant casualties and the allies retreated to their landing beaches at Helles and Gaba Tepe where they became involved in prolonged trench warfare. However at the time the truth of the situation remained largely hidden from the public.

By summer 1915 political pressure had led to small number of accredited journalists being permitted to report directly from the battlefront. Experienced war journalist Henry Nevinson travelled to the Dardenelles to cover the unfolding events on behalf of the Manchester Guardian and several regional newspapers.

Arriving on the island of Imbros in July 1915, Nevinson joined a number of other newspaper correspondents at a camp near the military’s headquarters including Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett who was representing Fleet Street and Charles Bean, the official correspondent of the Australian Journalists’ Association. In his first letter to the Manchester Guardian, Nevinson wrote poignantly of his initial impressions of Helles. “How often I have imagined this scene, and now it lies stretched before me full of immemorial history and of history now being daily made.”

War correspondents were still forbidden from mentioning strategy or negatively affecting the mood at home by reporting casualty figures or the poor conditions encountered by troops. Strict censorship could also hold up their letters for months. Nevinson’s biographer Angela John notes that Nevinson thus primarily relayed to readers the human stories of the ongoing conflict and the daily life of troops at Helles and Gaba Tepe, which became better known as Anzac Cove after the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps stationed there.

Nevinson was present at the August Offensive in which the allies, bolstered by new troops, sought to break the deadlock at Anzac Cove though a series of coordinated actions including additional landings at nearby Sulva Bay. A combination of inexperienced troops, poor planning, extreme heat and illness led to a further failure with casualties in excess of 12,000 men. Yet in order to keep reader’s hopes afloat, Nevinson’s reports were more encouraging, detailing the ‘Australians’ reckless courage’ and ‘Brilliant charge of the Irishmen at Sulva Bay.’

Nevinson was himself injured during the August Offensive. In an article published on 7 September he relayed the experience to Manchester Guardian readers. “I was upfront, in the midst of a tremendous bombardment with which the fighting began. Suddenly a shell burst close above my head with a frightful crash and I felt a blow just like an iron mallet.” After receiving basic first aid he returned to the front and over the next few days carried on as usual “for fear of losing nerve.”

Despite the restrictions imposed by censorship, the correspondents had significant opportunity to influence public understanding of events during the war. Charles Bean for example is credited with helping to bring about the feelings of national pride felt in Australia and New Zealand about the Anzacs’ actions during the campaign.

Yet each correspondent inevitably developed their own personal view of the operation. Ashmead-Bartlett had become increasingly critical of Hamilton’s actions, particularly after the events at Sulva Bay. After attempting to smuggle an unauthorised letter containing his views to the prime minister back in London, Bartlett was dismissed from the peninsula. He made his opinions clear however on his return to the UK which contributed to the recall of Hamilton to London in October and a chain of events which culminated in the end of the campaign.

Having left the Gallipoli peninsula in October to cover events in Salonika, Nevinson returned in December 1915. Preparations for a Christmas magazine and exchanges of fruit and cigarettes across the trenches were the focus of an article published on 28 December rather than the undercover evacuation of troops and equipment which was actually by then almost complete.

By the time the last allied soldier left the Dardanelles on 9 January 2016, over 100,000 men on both sides had perished. Nevinson was later called as a witness in an official investigation into the campaign during which Angela John notes that Nevinson refused to criticise Hamilton who he believed had been made a scapegoat by the government for the failure.

The Manchester Guardian also defended Hamilton it its own detailed analysis of the operation in Volume III of its History of the War series, published in early 1916. Illustrated with numerous photographs and maps, the four chapters concerning Gallipoli draw upon Nevinson’s reports and include Hamilton’s official dispatches. Yet the brutality of the events at Gallipoli and elsewhere were still not fully revealed until after the end of the war.

Nevinson’s own book The Dardanelles Campaign was published in 1918. He undertook several other commissions for the Manchester Guardian and in 1933 married regular contributor and fellow suffragist Evelyn Sharp.

The GNM Archive holds a complete set of the nine volumes of the Manchester Guardian History of the War which can be viewed by appointment in the GNM Archive reading room in King’s Cross, London. Past articles from the Guardian and the Observer can be accessed online via the Digital Archive.

Further reading

First world war history and the Manchester Guardian

First world war: how state and press kept truth off the front page

Foreign news coverage in the 1930s